In a nutshell

Levomilnacipran is the most noradrenergic SNRI, making it particularly suitable for patients with fatigue-predominant depression. Its clean receptor profile and minimal drug interactions are advantages. However, cardiac and urinary effects require monitoring in high-risk populations, especially those with cardiovascular disease or BPH.

- Choosing levomilnacipran over other SNRIs:

- Preferred for patients with predominant fatigue and low energy symptoms

- Highest norepinephrine-to-serotonin selectivity (2:1 ratio)

- Simultaneous serotonin and norepinephrine effects without the need for dose escalation

- Minimal drug interactions and weight-neutral profile

- Consider alternative SNRIs in patients with:

- Unstable cardiovascular conditions requiring strict BP control

- History of urinary obstruction or retention

- Need for established efficacy in anxiety or pain conditions

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

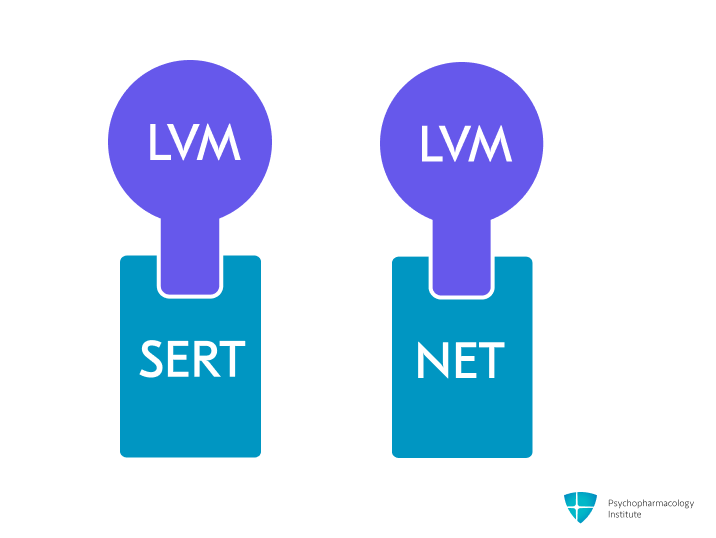

- Potent and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition (SNRI), by blocking SERT and NET.

- Greater potency for norepinephrine reuptake inhibition than serotonin (5HT: NE=1:2) [1].

- Serotonergic effects:

- Levomilnacipran inhibits both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake simultaneously across all doses, unlike venlafaxine and duloxetine, which have sequential effects [2].

- Noradrenergic effects:

- Most noradrenergic of all SNRIs

- Potential efficacy in alleviating the fatigue symptom cluster in MDD, though further research is needed [3].

- Better functional outcomes in patients with low baseline energy [4].

- Males may show greater improvement in work/activities and somatic symptoms, while younger women in retardation and somatic symptoms [5].

- Levomilnacipran shows no meaningful interaction with muscarinic, histaminergic receptors, or ion channels [6].

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism

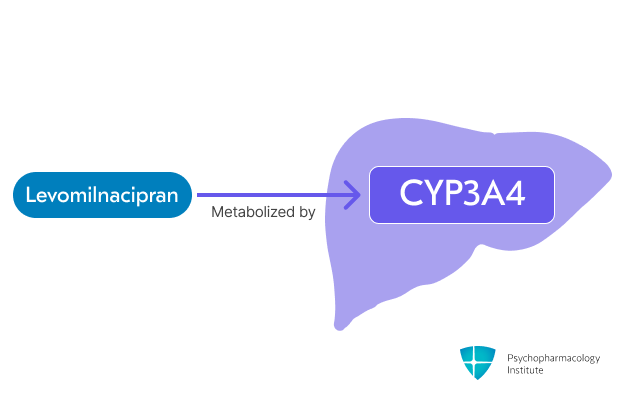

- Primarily metabolized via CYP3A4.

- Minor contribution by CYP2C8, 2C19, 2D6, and 2J2.

-

Drug interactions:

- Contraindicated with MAOIs.

- Allow 14 days after stopping MAOI before starting levomilnacipran.

- Allow 7 days after stopping levomilnacipran before starting MAOI.

- Levomilnacipran levels potentially increased by:

- Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole)

- Maximum dose should not exceed 80 mg/day [6].

- Alcohol

- The extended-release properties of levomilnacipran are disrupted by alcohol, risking rapid drug release. Concurrent use should be avoided [6].

- Contraindicated with MAOIs.

Half-life

- Levomilnacipran’s half-life is approximately 12 hours.

Dosage forms

- Capsules:

- 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, 120 mg.

- Fetzima.

- Capsules (Titration Pack):

- 20 mg & 40 mg.

- Fetzima Titration.

- Formulation considerations:

- Levomilnacipran is only available as extended-release capsules.

- Extended-release capsules should be taken once daily, with or without food.

- Capsules should be swallowed whole, not split, crushed, or chewed.

Indications

FDA-Approved Indications

Major Depressive Disorder

- First-line treatment option for major depression [7]

- No head-to-head comparisons with other antidepressants. Efficacy comparable to other second-generation antidepressants in network meta-analyses [8].

- May be particularly effective for patients with fatigue and low energy due to its higher noradrenergic potency compared to other SNRIs.

- Dosing:

- Initial: 20 mg once daily for 2 days

- Increase to 40 mg once daily

- May increase in increments of 40 mg at intervals of 2 or more days

- Target dose: 40-120 mg once daily

- Maximum dose: 120 mg once daily

Off-label Uses

- Off-label uses of levomilnacipran are primarily based on mechanism of action inferences as an SNRI, with limited direct clinical evidence.

Fibromyalgia

- Not FDA-approved for fibromyalgia management, despite its parent compound milnacipran having this indication [6].

Anxiety Disorders

- Limited evidence available for use in anxiety disorders.

- Improves depression-related anxiety in trials [9].

- No clinical trials have specifically evaluated levomilnacipran for anxiety disorders.

Vasomotor Symptoms of Menopause

- Limited evidence available; other SNRIs (venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine) have stronger evidence base for this indication [10].

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

- Limited evidence available;duloxetine, has FDA approval and a stronger evidence base for this indication [11].

Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

- Limited evidence available duloxetinehas FDA approval and a stronger evidence base for this indication [12].

Side Effects

Most common side effects

Gastrointestinal

- Nausea (17% incidence, most common adverse effect) [6]

- Leading cause of discontinuation (1.5%)

- Less common than with venlafaxine

- More severe early in treatment

- Requires slow titration for tolerance development

- Dry mouth (10% incidence)

- Constipation (9% incidence)

- Recommend increasing fluid and fiber intake [13,14].

- Vomiting (5% incidence)

- Decreased appetite (3% incidence)

- Weight neutral in short-term: -0.5 kg vs placebo +0.1 kg at 8 weeks [15–18]

- Maintains weight neutrality long-term: -0.5 to -0.55 kg weight loss over 24-48 weeks [19,20]

Other common side effects

- Cardiovascular effects

- Tachycardia (6% incidence) [6]

- Elevated blood pressure

- Although levominacipran can cause BP elevations, hypertension is uncommon (1.8% vs 1.2% with placebo) [21].

- 10.4% of patients progressed from normal/pre-hypertensive to Stage I/II hypertension (vs 7.1% with placebo)

- Monitor BP and HR at baseline and throughout treatment.

- Discontinue levomilnacipran if sustained hypertension develops.

- Although levominacipran can cause BP elevations, hypertension is uncommon (1.8% vs 1.2% with placebo) [21].

- Orthostatic hypotension: 11.6% (vs 9.7% placebo)

- Urinary hesitation (4-6% incidence) [21]

- Dose-dependent risk. Higher in patients prone to obstructive urinary disorders.

- Advise patients to report any difficulty urinating.

- If symptoms develop, consider discontinuing levomilnacipran or reducing the dose.

- Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction [21]

- Dose-dependent.

- More common in males.

- Erectile dysfunction (6-10% incidence)

- Ejaculatory disorder (5% incidence)

- Testicular pain (4% incidence)

- Incidence was <2% in female patients [6].

- Ranking of risk: SSRIs and venlafaxine > tricyclics > other SNRIs [22]

- Consider reducing the dose, or switching to an antidepressant with a lower risk of sexual dysfunction, such as bupropion or mirtazapine.

- Sweating (9 % incidence)

- Consider switching to an SSRI

- Terazosin and oxybutynin have shown efficacy in reducing ADIES [23,24].

- Discontinuation syndrome

- Increased incidence at higher dosages, possibly related to noradrenergic effects.

- SNRIs, paroxetine, and mirtazapine have the highest risk among antidepressants [25].

- Taper the dose over two to four weeks to reduce discontinuation emergent adverse events [26].

- Dizziness (8% incidence)

- Insomnia (5% incidence)

- Less frequent than with other SNRIs

Severe side effects

- Serotonin syndrome

- Risk increases with MAOIs and other serotonergic drugs.

- Life-threatening risk has been reported with SNRIs alone or with serotonergic drugs/MAOIs; monitor for mental changes, autonomic instability, hyperreflexia, and GI symptoms.

- Avoid tryptophan and watch triptans carefully [6].

- Ocular effects

- Acute angle closure glaucoma reported [27]

- Higher risk in females >50y, Asians/Inuit, hyperopia, family history.

- Mechanism likely serotonergic/adrenergic effects on pupil/pressure [28]

- Bleeding risk

- The absolute risk remains low in most patients, but is significantly elevated when combined with NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants [29].

- Data quality remains low due to the absence of randomized trials and potential confounding by depression.

- Monitor closely during initial months of combined antidepressant-anticoagulant therapy, particularly in patients with a history of intracranial or GI hemorrhage [30].

- The absolute risk remains low in most patients, but is significantly elevated when combined with NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants [29].

- Hyponatremia

- No hyponatremia cases reported with levomilnacipran in trials, but SNRIs can cause SIADH-related hyponatremia [6].

- Ranking of risk [31]:

- MAOIs > SNRIs > SSRIs > TCAs > Mirtazapine

- Special caution in elderly patients, patients taking diuretics or who are otherwise volume-depleted.

Use in special populations

Pregnancy

- No data are available on human pregnancy outcomes with levomilnacipran.

- Levomilnacipran did not increase congenital malformations in rats (up to 8x human dose) or rabbits (16x human dose) [6].

- Antidepressant use during pregnancy was associated with a 32% increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage (RR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.17–1.48) [32].

- SNRIs higher risk than SSRIs (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.41-1.85)

Breastfeeding

- No specific data exist for levomilnacipran in breast milk.

- Evidence from milnacipran (parent compound):

- Low milk levels (relative infant dose 2.8% of maternal dose)

- Suggests minimal infant exposure

- Breastfed infants should be monitored for:

- Sedation

- Poor feeding patterns

- Weight gain adequacy

- For treatment-naive breastfeeding patients, antidepressants other than SNRI are generally preferred [33].

Hepatic impairment

- Levomilnacipran undergoes minimal hepatic elimination. No dose adjustments are required for patients with hepatic impairment, regardless of severity (Child-Pugh scores 1-13) [6].

Renal impairment

- CrCl ≥60 mL/minute:

- No dosage adjustment necessary

- CrCl 30 to 59 mL/minute:

- Maximum dose: 80 mg

- CrCl 15 to 29 mL/minute:

- Maximum dose: 40 mg

- End-stage renal disease (ESRD):

- Use is not recommended

Elderly

- No age-based dose adjustment is required for levomilnacipran, despite elderly patients (>65 years) showing modestly increased exposure compared to younger adults [6].

- Clinicians should monitor elderly patients for hyponatremia, a known risk with SNRIs and SSRIs.

Brand names

* US: Fetzima, Fetzima Titration – Canada: Fetzima – Other countries/regions: Cipran, Levomil, Fetzima.

References

- Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2014 Mar-Apr). Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors: A Pharmacological Comparison. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(3–4), 37. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4008300/

- Kasper, S., & Pail, G. (2010). Milnacipran: A unique antidepressant? Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 6, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S11777

- Gautam, M., Kaur, M., Jagtap, P., & Krayem, B. (2019). Levomilnacipran: More of the Same? The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 21(5), 27423. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.19nr02475

- Thase, M. E., Gommoll, C., Chen, C., Kramer, K., & Sambunaris, A. (2016). Effects of levomilnacipran extended-release on motivation/energy and functioning in adults with major depressive disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 31(6), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0000000000000138

- Freeman, M. P., Fava, M., Gommoll, C., Chen, C., Greenberg, W. M., & Ruth, A. (2016). Effects of levomilnacipran ER on fatigue symptoms associated with major depressive disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 31(2), 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0000000000000104

- Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (2024). FETZIMA® (levomilnacipran) extended-release capsules – Prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/204168s012lbl.pdf

- Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Adams, C., Bahji, A., Beaulieu, S., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Blumberger, D. M., Brietzke, E., Chakrabarty, T., Do, A., Frey, B. N., Giacobbe, P., Gratzer, D., Grigoriadis, S., Habert, J., Ishrat Husain, M., Ismail, Z., McGirr, A., … Milev, R. V. (2024). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023 : Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can. J. Psychiatry, 69(9), 641–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437241245384

- Wagner, G., Schultes, M.-T., Titscher, V., Teufer, B., Klerings, I., & Gartlehner, G. (2018). Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran, vilazodone and vortioxetine compared with other second-generation antidepressants for major depressive disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 228, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.056

- Montgomery, S. A., Mansuy, L., Ruth, A., Bose, A., Li, H., & Li, D. (2013). Efficacy and Safety of Levomilnacipran Sustained Release in Moderate to Severe Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Proof-of-Concept Study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(4), 6175. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m08141

- Berhan, Y., & Berhan, A. (2014). Is desvenlafaxine effective and safe in the treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms? A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized double-blind controlled studies. Ethiop. J. Health Sci., 24(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v24i3.4

- Ormseth, M. J., Scholz, B. A., & Boomershine, C. S. (2011). Duloxetine in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Patient Preference and Adherence, 5, 343–356. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S16358

- Qaseem, A., Wilt, T. J., McLean, R. M., Forciea, M. A., Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, Denberg, T. D., Barry, M. J., Boyd, C., Chow, R. D., Fitterman, N., Harris, R. P., Humphrey, L. L., & Vijan, S. (2017). Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(7), 514–530. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2367

- Anti, M., Pignataro, G., Armuzzi, A., Valenti, A., Iascone, E., Marmo, R., Lamazza, A., Pretaroli, A. R., Pace, V., Leo, P., Castelli, A., & Gasbarrini, G. (1998). Water supplementation enhances the effect of high-fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepato-Gastroenterology, 45(21), 727–732.

- Markland, A. D., Palsson, O., Goode, P. S., Burgio, K. L., Busby-Whitehead, J., & Whitehead, W. E. (2013). Association of Low Dietary Intake of Fiber and Liquids With Constipation: Evidence From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108(5), 796–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.73

- Asnis, G. M., Bose, A., Gommoll, C. P., Chen, C., & Greenberg, W. M. (2013). Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran sustained release 40 mg, 80 mg, or 120 mg in major depressive disorder: A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(3), 242–248. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m08197

- Sambunaris, A., Bose, A., Gommoll, C. P., Chen, C., Greenberg, W. M., & Sheehan, D. V. (2014). A phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose study of levomilnacipran extended-release in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 34(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000060

- Bakish, D., Bose, A., Gommoll, C., Chen, C., Nunez, R., Greenberg, W. M., Liebowitz, M., & Khan, A. (2014). Levomilnacipran ER 40 mg and 80 mg in patients with major depressive disorder: A phase III, randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience: JPN, 39(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.130040

- Gommoll, C. P., Greenberg, W. M., & Chen, C. (2014). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of flexible doses of levomilnacipran ER (40-120 mg/day) in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Drug Assessment, 3(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.3109/21556660.2014.884505

- Mago, R., Forero, G., Greenberg, W. M., Gommoll, C., & Chen, C. (2013). Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: Results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clinical Drug Investigation, 33(10), 761–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-013-0126-5

- Shiovitz, T., Greenberg, W. M., Chen, C., Forero, G., & Gommoll, C. P. (2014). A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial of the Efficacy and Safety of Levomilnacipran ER 40-120mg/day for Prevention of Relapse in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(1–2), 10–22.

- Asnis, G. M., & Henderson, M. A. (2015). Levomilnacipran for the treatment of major depressive disorder: A review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2147/NDT.S54710

- Winter, J., Curtis, K., Hu, B., & Clayton, A. H. (2022). Sexual dysfunction with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatments: Impact, assessment, and management. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 21(7), 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2022.2049753

- Ghaleiha, A., Shahidi, K. M., Afzali, S., & Matinnia, N. (2013). Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 17(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

- Grootens, K. P. (2011). Oxybutynin for antidepressant-induced hyperhidrosis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(3), 330–331. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10091348

- Horowitz, M. A., Framer, A., Hengartner, M. P., Sørensen, A., & Taylor, D. (2023). Estimating Risk of Antidepressant Withdrawal from a Review of Published Data. CNS Drugs, 37(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y

- Perahia, D. G., Kajdasz, D. K., Desaiah, D., & Haddad, P. M. (2005). Symptoms following abrupt discontinuation of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 89(1–3), 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.003

- Narayanan, V. (2019). Ocular Adverse Effects of Antidepressants – Need for an Ophthalmic Screening and Follow up Protocol. Ophthalmology Research: An International Journal, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.9734/or/2019/v10i330107

- Wiciński, M., Kaluzny, B. J., Liberski, S., Marczak, D., Seredyka-Burduk, M., & Pawlak-Osińska, K. (2019). Association between serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and acute angle closure: What is known? Survey of Ophthalmology, 64(2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.09.006

- McFarland, D., Merchant, D., Khandai, A., Mojtahedzadeh, M., Ghosn, O., Hirst, J., Amonoo, H., Chopra, D., Niazi, S., Brandstetter, J., Gleason, A., Key, G., & di Ciccone, B. L. (2023). Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Bleeding Risk: Considerations for the Consult-Liaison Psychiatrist. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25(3), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01411-1

- Rahman, A. A., Platt, R. W., Beradid, S., Boivin, J.-F., Rej, S., & Renoux, C. (2024). Concomitant Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors With Oral Anticoagulants and Risk of Major Bleeding. JAMA Network Open, 7(3), e243208. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3208

- Gheysens, T., Van Den Eede, F., & De Picker, L. (2024). The risk of antidepressant-induced hyponatremia: A meta-analysis of antidepressant classes and compounds. European Psychiatry, 67(1), e20. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2024.11

- Jiang, H., Xu, L., Li, Y., Deng, M., Peng, C., & Ruan, B. (2016). Antidepressant use during pregnancy and risk of postpartum hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 83, 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.001

- Sriraman, N. K., Melvin, K., Meltzer-Brody, S., & the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. (2015). ABM Clinical Protocol #18: Use of Antidepressants in Breastfeeding Mothers. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(6), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.29002