In a nutshell

Duloxetine is suitable for patients with comorbid pain conditions, given its unique FDA approvals for fibromyalgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and chronic musculoskeletal pain. Duloxetine use is discouraged in patients with liver disease or a history of heavy alcohol use due to the risk of hepatic toxicity. Compared to venlafaxine, duloxetine offers simplified dosing and consistent noradrenergic effects, with a lower risk of hypertension and discontinuation syndrome.

- Choosing duloxetine over other SNRIs:

- Preferred for patients with pain syndromes, given its unique FDA approvals.

- Simplified dosing: Initial and target dose of 60 mg/day without titration in most cases .

- Consistent noradrenergic effects at all doses.

- Lower risk of hypertension discontinuation symptoms compared to venlafaxine.

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

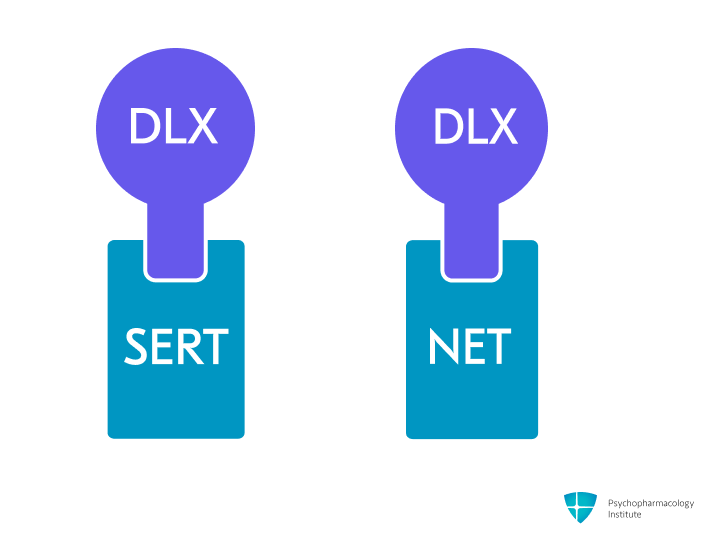

- Potent and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition (SNRI), by blocking SERT and NET.

- Weak dopamine reuptake inhibition [1].

- Noradrenergic effects:

- NET inhibition may underpin duloxetine’s efficacy in neuropathic pain and cognitive symptoms [2,3].

- Greater noradrenergic activity compared to venlafaxine, due to its lower serotonin-to-norepinephrine (5-HT: NE) affinity ratio of 10:1 (compared to venlafaxine’s 30:1) [1].

- Sequential activation (5-HT first, then NE) [1].

- Duloxetine demonstrates minimal affinity for histaminergic, muscarinic, and α1-adrenergic receptors, contributing to its favorable side-effect profile.

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism

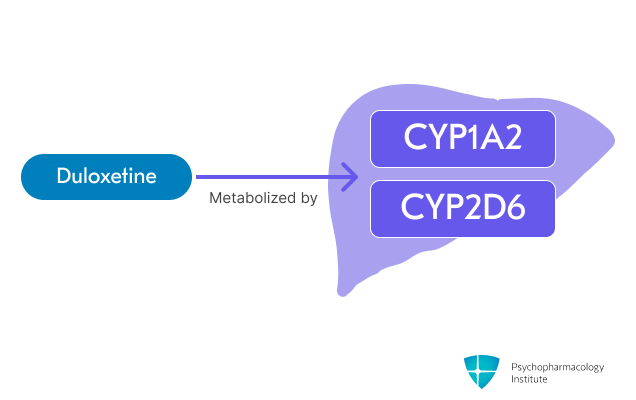

- Primarily metabolized through two major pathways [4]:

- CYP1A2 (primary).

- CYP2D6 (secondary).

- Duloxetine levels potentially increased by:

- Fluvoxamine (CYP1A2 inhibitor), increases duloxetine exposure 6-fold.

- Other significant CYP1A2 inhibitors: ciprofloxacin, enoxacin [5].

- Paroxetine (CYP2D6 inhibitor) increases duloxetine AUC by 60%.

- Similar effects are expected with fluoxetine and quinidine.

- Duloxetine levels potentially reduced by:

- Smoking. It reduces duloxetine AUC by ~33% (CYP1A2 induction).

- Duloxetine is a moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor.

- It may increase the concentrations of CYP2D6 substrates.

- As a CYP2D6 inhibitor, duloxetine can increase concentrations of:

- Tricyclic antidepressants.

- Paroxetine and fluoxetine.

- Aripiprazole and risperidone.

- Atomoxetine.

- Contraindicated with MAOIs.

Half-life

- Duloxetine half-life is approximately 12 (8 to 17) hours, prolonged in renal and hepatic failure.

Dosage forms

Dosage forms

- Delayed-release:

- Capsules (particles):

- 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, 60 mg.

- Conventional capsules, intended to be swallowed whole; do not chew or crush.

- Generic, Cymbalta.

- Capsules (sprinkle):

- 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, 60 mg.

- Delayed-release sprinkle capsules, designed for patients who have difficulty swallowing intact capsules.

- Drizalma Sprinkle.

- Capsules (particles):

- Formulation considerations:

- Duloxetine is only available in delayed-release formulations.

Indications

FDA-Approved Indications

Major depressive disorder

- First-line treatment option for major depressive disorder [6].

- SNRIs may be particularly effective for patients with anhedonia and fatigue symptom clusters [7].

- Duloxetine may be particularly effective in depressed patients with chronic pain comorbidity [6,7].

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 40-60 mg/day (divided twice daily or once daily).

- Sensitive patients: Start at 30 mg once daily for 1 week before increasing to minimize side effects [8].

- Increase by 30 mg increments at intervals of ≥3 weeks.

- Target dose: 60 mg/day.

- Doses >60 mg/day did not show additional benefit in clinical trials, but may be considered in individual patients showing partial response after ≥4 weeks [9].

- Maximum recommended dose: 120 mg/day.

- Starting dose: 40-60 mg/day (divided twice daily or once daily).

Generalized anxiety disorder

- SSRIs (escitalopram, paroxetine) and select SNRIs (duloxetine, venlafaxine) are first-line options for GAD [10].

- Duloxetine shows comparable efficacy to other first-line agents [11].

- Dosing:

- Initial: 60 mg once daily.

- Alternative start: 30 mg once daily for 1 week.

- Target: 60 mg once daily.

- Maximum: 120 mg/day.

- For dose escalation: Increase by 30 mg increments at ≥ 1-week intervals [8].

- Initial: 60 mg once daily.

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy

- First-line treatment option with strong evidence base [12].

- Dosing:

- Initial: 60 mg once daily.

- For tolerability, consider a 20 mg/day start.

- Since diabetes is frequently complicated by renal disease, a lower starting dose and gradual increase should be considered for patients with renal impairment.

- Maximum: 60 mg/day.

- Higher doses showed no additional benefit and are less well-tolerated [8].

Fibromyalgia

- Recommended as a first-line pharmacological treatment [13].

- Efficacy demonstrated in both adults and adolescents ≥13 years [14].

- Adult dosing:

- Initial: 30 mg once daily for 1 week.

- Target: 60 mg once daily.

- Maximum: 60 mg/day [8,15].

- A large review (n=2,249) shows doses below 30 mg are ineffective, while doses above 60 mg provide no additional benefit [16].

Chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Effective for both chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis [17].

- Recommended as an alternative when NSAIDs are contraindicated or ineffective [18,19].

- Dosing:

- Initial: 30 mg once daily for 1-2 weeks.

- Target: 60 mg once daily.

- Maximum: 60 mg/day.

- For osteoarthritis: Some evidence for doses up to 120 mg/day, but with increased adverse effects [20].

Off-Label Uses

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against duloxetine for the treatment of PTSD [21].

- The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline recommends paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine [22].

- Two small open studies suggest efficacy [23,24].

- The target dose was 60-120 mg.

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN)

- Demonstrated efficacy in randomized clinical trials [3]

- Recommended in ASCO guidelines for CIPN [25].

Stress urinary incontinence

- Evidence supports use in both men and women [26].

- It may be offered as second-line therapy if women prefer pharmacological to surgical treatment or are not suitable for surgical treatment [27].

Side Effects

Most common side effects

Gastrointestinal

- Nausea (20% incidence)

- Most common adverse effect leading to discontinuation.

- Higher risk during the first week of treatment.

- Can be minimized by starting at lower doses.

- Recommend taking with food and ginger supplementation [28]

- Dry mouth (15% incidence)

- Constipation (11% incidence)

Other common side effects

- Weight gain

- Higher doses (120 mg) led to a modest but statistically significant weight gain (+0.9 kg) compared to placebo. A 52-week open-label study found a mean weight gain of 1.1 kg, suggesting minimal long-term effects [29].

- Discontinuation syndrome

- Increased incidence at higher dosages, possibly related to noradrenergic effects.

- SNRIs, paroxetine, and mirtazapine have the highest risk among antidepressants [30].

- Taper the dose over two to four weeks to reduce discontinuation effects [31].

- Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction

- More common in males.

- Specific difficulty with orgasm/ejaculation [8].

- Ranking of risk: SSRIs and venlafaxine > tricyclics > other SNRIs [32].

- Sleep and alertness

- Insomnia (10% incidence) is marginally more frequent than somnolence (8% incidence).

- Consider morning dosing if insomnia is problematic.

- Dizziness (9% incidence)

- Sweating (7% incidence)

- Dose-related side effect.

- Consider dose reduction if clinically feasible [33].

Severe side effects

- Hepatotoxicity

- Contraindicated in patients with substantial alcohol use or chronic liver disease.

- Rare but potentially severe, including fatal cases.

- Onset ~50 days; primarily hepatocellular pattern.

- Monitor closely when combined with medications affecting CYP1A2 or CYP2D6 pathways, especially at higher doses.

- Discontinue if jaundice or other evidence of liver dysfunction appears [34].

- Bleeding risk

- The absolute risk remains low in most patients. The risk is significantly elevated when combined with NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants [35].

- Data quality remains low due to the absence of randomized trials and potential confounding by depression.

- Monitor closely patients on blood thinners, particularly in the initial months of combined therapy [36].

- The absolute risk remains low in most patients. The risk is significantly elevated when combined with NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants [35].

- Hyponatremia

- Ranking of risk [37]:

- MAOIs > SNRIs > SSRIs > TCAs > Mirtazapine

- Special caution in elderly patients, patients taking diuretics, or who are otherwise volume-depleted.

- For hyponatremia-prone patients:

- Mirtazapine should be considered the antidepressant of choice.

- SNRIs should be prescribed more cautiously than SSRIs.

- CYP2D6 poor metabolizers may be at increased risk of antidepressant-induced hyponatremia, although evidence is somewhat inconsistent [38].

- Ranking of risk [37]:

- Ocular effects

- Acute angle closure glaucoma and cataracts reported.

- Acute angle closure glaucoma risk: TCAs > SSRIs > SNRIs > Mirtazapine > MAOI [39].

- Higher risk in females >50 years, patients of Asian or Inuit descent, hyperopia, and family history.

- Mechanism likely serotonergic/adrenergic effects on pupil/pressure [40].

- Serotonin syndrome

- Risk increases with other serotonergic drugs.

- Life-threatening risk has been reported with SNRIs alone [41]or with serotonergic drugs/MAOIs.

- Avoid tryptophan and watch triptans carefully [8].

- Fracture risk

- SSRIs and SNRIs, including duloxetine, are linked to reduced bone mineral density and increased fracture risk, particularly in older adults [42,43].

- The association observed in cohort studies may be subject to confounding factors (frailty/sarcopenia, visual/vestibular impairment) [44].

- SSRIs and SNRIs, including duloxetine, are linked to reduced bone mineral density and increased fracture risk, particularly in older adults [42,43].

Use in special populations

Pregnancy

- First-trimester safety:

- Congenital malformations risk:

- A 2016 systematic review concluded that there was no increased risk of congenital malformations among 668 pregnancies with first-trimester exposures to duloxetine [45].

- A 2020 study reported increased total urinary malformations (adjusted OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.14-3.14) [46].

- No increased cardiac malformations.

- Congenital malformations risk:

- Pregnancy complications:

- No increased risk of preeclampsia or hypertensive disorders [46]

- Antidepressant use during pregnancy was associated with a 32% increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage (RR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.17–1.48) [47].

- SNRIs have higher risk than SSRIs (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.41-1.85).

- Duloxetine risk is similar to SNRI class (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.08-2.18) [46].

Breastfeeding

- Generally considered acceptable during breastfeeding due to minimal infant exposure [48].

- Infant serum levels <1% of maternal levels.

- When initiating antidepressant therapy in treatment-naive patients:

- First-line options: SSRIs [49].

- SNRIs, including duloxetine, may be considered as an alternative [50].

- May reduce breastfeeding initiation rates [51].

- Rare reports of elevated prolactin/galactorrhea [52].

- Breastfed infants should be monitored for:

- Sedation.

- Poor feeding patterns.

- Weight gain adequacy.

- Normal development in followed cases, with no reported adverse effects in breastfed infants. [53].

- Breastfeeding can typically be continued for patients treated with an SNRI during pregnancy [54].

Hepatic impairment

- Duloxetine should be avoided in patients with hepatic impairment or risk factors for hepatic impairment (e.g., alcoholism) [34].

- When use is deemed necessary in Child-Pugh Class A:

- Start at ≤30 mg once daily.

- Titrate no more frequently than every 2-4 weeks.

- Maximum dose: 30 mg/day.

- Monitor closely for adverse effects.

- Contraindicated in:

- Child-Pugh Class B and C.

- Any substantial liver dysfunction.

Renal impairment

- CrCl ≥30 mL/minute:

- No dosage adjustment needed.

- Mild to moderate impairment doesn’t significantly affect clearance.

- CrCl <30 mL/minute or End-Stage Renal Disease:

- Generally avoid use.

- If necessary:

- Start at 30 mg daily.

- Maximum: 60 mg once daily.

- Monitor closely for adverse effects.

Elderly

- Dosage adjustment is not necessary [8].

- Consider lower starting doses (20 mg/day).

- Lower maintenance doses (30-60 mg/day) recommended.

Brand names

- US: Cymbalta

- Canada: Cymbalta, ACCEL-Duloxetine; AG-Duloxetine; APO-Duloxetine; Auro-Duloxetine; BIO-Duloxetine; JAMP-Duloxetine; M-Duloxetine; Mar-Duloxetine; MINT-Duloxetine; NRA-Duloxetine; PMS-Duloxetine; RAN-Duloxetine; RIVA-Duloxetine; SANDOZ Duloxetine; TEVA-DuloxetineRIVA-Duloxetine, SANDOZ Duloxetine, TEVA-Duloxetine

- Other countries/regions: Andepra, Ariclaim, C yalta, Cendu, Cimal, Dell, Deloxi, Depreta, Devixdol, Dobalta, Drugtech cimal, Du two, Duax r, Duceten, Dulatine, Dumore, Durotine, Duxetin, Duxiauro, Duxvitae, Dytrex, Hilux, Ilario, Joytor, Julotin, Lenno vaxyn, Lervitan, Limbaxia, Lodux, Macxetine, Magax, Medlux, Nexetin, Nitexol, Nitidex, Nudep, Qalih, Realta, Rimalix, Splypax, Sympta, Tixol, Tobalta, Velija, Xeristar, Yentreve, Zedulox, Zenbar

References

- Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2014 Mar-Apr). Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors: A Pharmacological Comparison. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(3–4), 37. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4008300/

- Kremer, M., Yalcin, I., Goumon, Y., Wurtz, X., Nexon, L., Daniel, D., Megat, S., Ceredig, R. A., Ernst, C., Turecki, G., Chavant, V., Théroux, J.-F., Lacaud, A., Joganah, L.-E., Lelievre, V., Massotte, D., Lutz, P.-E., Gilsbach, R., Salvat, E., & Barrot, M. (2018). A Dual Noradrenergic Mechanism for the Relief of Neuropathic Allodynia by the Antidepressant Drugs Duloxetine and Amitriptyline. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(46), 9934–9954. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1004-18.2018

- Smith, E. M. L., Pang, H., Cirrincione, C., Fleishman, S., Paskett, E. D., Ahles, T., Bressler, L. R., Fadul, C. E., Knox, C., Le-Lindqwister, N., Gilman, P. B., Shapiro, C. L., & Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. (2013). Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 309(13), 1359–1367. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.2813

- Lobo, E. D., Heathman, M., Kuan, H.-Y., Reddy, S., O’Brien, L., Gonzales, C., Skinner, M., & Knadler, M. P. (2010). Effects of Varying Degrees of Renal Impairment on the Pharmacokinetics of Duloxetine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 49(5), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.2165/11319330-000000000-00000

- Nelson, et al. (2006). The Safety and Tolerability of Duloxetine Compared With Paroxetine and Placebo: A Pooled Analysis of 4 Clinical Trials.

- Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Adams, C., Bahji, A., Beaulieu, S., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Blumberger, D. M., Brietzke, E., Chakrabarty, T., Do, A., Frey, B. N., Giacobbe, P., Gratzer, D., Grigoriadis, S., Habert, J., Ishrat Husain, M., Ismail, Z., McGirr, A., … Milev, R. V. (2024). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023 : Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can. J. Psychiatry, 69(9), 641–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437241245384

- Murawiec, S., & Krzystanek, M. (2021). Symptom Cluster-Matching Antidepressant Treatment: A Case Series Pilot Study. Pharmaceuticals, 14(6), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060526

- Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (2023). Cymbalta® (Duloxetine Delayed-Release Capsules) Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/021427s055s057lbl.pdf

- Nelson, C. (2023). Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: Pharmacology, administration, and side effects. In P. P. Roy-Byrne & D. Solomon (Eds.), UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/serotonin-norepinephrine-reuptake-inhibitors-pharmacology-administration-and-side-effects

- Bandelow, B., Allgulander, C., Baldwin, D. S., Costa, D. L. da C., Denys, D., Dilbaz, N., Domschke, K., Eriksson, E., Fineberg, N. A., Hättenschwiler, J., Hollander, E., Kaiya, H., Karavaeva, T., Kasper, S., Katzman, M., Kim, Y.-K., Inoue, T., Lim, L., Masdrakis, V., … Zohar, J. (2023). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders – Version 3. Part I: Anxiety disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry, 24(2), 79–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2022.2086295

- Norman, T. R., & Olver, J. S. (2008). Duloxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 4(6), 1169–1180. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s2820

- Ormseth, M. J., Scholz, B. A., & Boomershine, C. S. (2011). Duloxetine in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Patient Preference and Adherence, 5, 343–356. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S16358

- Macfarlane, G. J., Kronisch, C., Dean, L. E., Atzeni, F., Häuser, W., Fluß, E., Choy, E., Kosek, E., Amris, K., Branco, J., Dincer, F., Leino-Arjas, P., Longley, K., McCarthy, G. M., Makri, S., Perrot, S., Sarzi-Puttini, P., Taylor, A., & Jones, G. T. (2017). EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 76(2), 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724

- Upadhyaya, H. P., Arnold, L. M., Alaka, K., Qiao, M., Williams, D., & Mehta, R. (2019). Efficacy and safety of duloxetine versus placebo in adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal, 17(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-019-0325-6

- Murakami, M., Osada, K., Ichibayashi, H., Mizuno, H., Ochiai, T., Ishida, M., Alev, L., & Nishioka, K. (2017). An open-label, long-term, phase III extension trial of duloxetine in Japanese patients with fibromyalgia. Modern Rheumatology, 27(4), 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2016.1245237

- Lunn, M. P., Hughes, R. A., & Wiffen, P. J. (2014). Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014(1), CD007115. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3

- Qaseem, A., Wilt, T. J., McLean, R. M., Forciea, M. A., Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, Denberg, T. D., Barry, M. J., Boyd, C., Chow, R. D., Fitterman, N., Harris, R. P., Humphrey, L. L., & Vijan, S. (2017). Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(7), 514–530. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2367

- Chou, R., Deyo, R., Friedly, J., Skelly, A., Weimer, M., Fu, R., Dana, T., Kraegel, P., Griffin, J., & Grusing, S. (2017). Systemic Pharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(7), 480. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2458

- Chou, R., Atlas, S., & Law, K. (2024). Management of subacute and chronic low back pain – UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-subacute-and-chronic-low-back-pain/print?source=history_widget

- Chappell, A. S., Ossanna, M. J., Liu-Seifert, H., Iyengar, S., Skljarevski, V., Li, L. C., Bennett, R. M., & Collins, H. (2009). Duloxetine, a centrally acting analgesic, in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: A 13-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pain, 146(3), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.024

- Schnurr, P. P., Hamblen, J. L., Wolf, J., Coller, R., Collie, C., Fuller, M. A., Holtzheimer, P. E., Kelly, U., Lang, A. J., McGraw, K., Morganstein, J. C., Norman, S. B., Papke, K., Petrakis, I., Riggs, D., Sall, J. A., Shiner, B., Wiechers, I., & Kelber, M. S. (2024). The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder: Synopsis of the 2023 U.s. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.s. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med., 177(3), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-2757

- Williams, T., Phillips, N. J., Stein, D. J., & Ipser, J. C. (2022). Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., 3, CD002795. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002795.pub3

- Walderhaug, E., Kasserman, S., Aikins, D., Vojvoda, D., Nishimura, C., & Neumeister, A. (2010). Effects of duloxetine in treatment-refractory men with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry, 43(2), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1237694

- Villarreal, G., Cañive, J. M., Calais, L. A., Toney, G., & Smith, A. K. (2010). Duloxetine in military posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 43(3), 26–34.

- Loprinzi, C. L., Lacchetti, C., Bleeker, J., Cavaletti, G., Chauhan, C., Hertz, D. L., Kelley, M. R., Lavino, A., Lustberg, M. B., Paice, J. A., Schneider, B. P., Lavoie Smith, E. M., Smith, M. L., Smith, T. J., Wagner-Johnston, N., & Hershman, D. L. (2020). Prevention and Management of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy in Survivors of Adult Cancers: ASCO Guideline Update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(28), 3325–3348. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.01399

- Li, J., Yang, L., Pu, C., Tang, Y., Yun, H., & Han, P. (2013). The role of duloxetine in stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Urology and Nephrology, 45(3), 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-013-0410-6

- NICE Guidance– Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. (2019). BJU International, 123(5), 777–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14763

- Kelly, K., Posternak, M., & Jonathan, E. A. (2008). Toward achieving optimal response: Understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/kkelly

- Wise, T. N., Perahia, D. G. S., Pangallo, B. A., Losin, W. G., & Wiltse, C. G. (2006). Effects of the Antidepressant Duloxetine on Body Weight: Analyses of 10 Clinical Studies. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 8(5), 269–278. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1764530/

- Horowitz, M. A., Framer, A., Hengartner, M. P., Sørensen, A., & Taylor, D. (2023). Estimating Risk of Antidepressant Withdrawal from a Review of Published Data. CNS Drugs, 37(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y

- Perahia, D. G., Kajdasz, D. K., Desaiah, D., & Haddad, P. M. (2005). Symptoms following abrupt discontinuation of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 89(1–3), 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.003

- Winter, J., Curtis, K., Hu, B., & Clayton, A. H. (2022). Sexual dysfunction with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatments: Impact, assessment, and management. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 21(7), 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2022.2049753

- Thompson, S., Compton, L., Chen, J.-L., & Fang, M.-L. (2021). Pharmacologic treatment of antidepressant-induced excessive sweating: A systematic review. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 48, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.15761/0101-60830000000279

- Vuppalanchi, R., Hayashi, P. H., Chalasani, N., Fontana, R. J., Bonkovsky, H., Saxena, R., Kleiner, D., Hoofnagle, J. H., & Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). (2010). Duloxetine hepatotoxicity: A case-series from the drug-induced liver injury network. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 32(9), 1174–1183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04449.x

- McFarland, D., Merchant, D., Khandai, A., Mojtahedzadeh, M., Ghosn, O., Hirst, J., Amonoo, H., Chopra, D., Niazi, S., Brandstetter, J., Gleason, A., Key, G., & di Ciccone, B. L. (2023). Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Bleeding Risk: Considerations for the Consult-Liaison Psychiatrist. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25(3), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01411-1

- Rahman, A. A., Platt, R. W., Beradid, S., Boivin, J.-F., Rej, S., & Renoux, C. (2024). Concomitant Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors With Oral Anticoagulants and Risk of Major Bleeding. JAMA Network Open, 7(3), e243208. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3208

- Gheysens, T., Van Den Eede, F., & De Picker, L. (2024). The risk of antidepressant-induced hyponatremia: A meta-analysis of antidepressant classes and compounds. European Psychiatry, 67(1), e20. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2024.11

- Variation in the CYP2D6 gene is associated with a lower serum sodium concentration in patients on antidepressants – PMC. (n.d.). Retrieved November 24, 2024, from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2767286/

- Narayanan, V. (2019). Ocular Adverse Effects of Antidepressants – Need for an Ophthalmic Screening and Follow up Protocol. Ophthalmology Research: An International Journal, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.9734/or/2019/v10i330107

- Wiciński, M., Kaluzny, B. J., Liberski, S., Marczak, D., Seredyka-Burduk, M., & Pawlak-Osińska, K. (2019). Association between serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and acute angle closure: What is known? Survey of Ophthalmology, 64(2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.09.006

- Gelener, P., Gorgulu, U., Kutlu, G., Ucler, S., & Inan, L. E. (2011). Serotonin syndrome due to duloxetine. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 34(3), 127–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0b013e31821b3aa0

- Mercurio, M., de Filippis, R., Spina, G., De Fazio, P., Segura-Garcia, C., Galasso, O., & Gasparini, G. (n.d.). The use of antidepressants is linked to bone loss: A systematic review and metanalysis. Orthopedic Reviews, 14(6), 38564. https://doi.org/10.52965/001c.38564

- Tamblyn, R., Bates, D. W., Buckeridge, D. L., Dixon, W. G., Girard, N., Haas, J. S., Habib, B., Iqbal, U., Li, J., & Sheppard, T. (2020). Multinational Investigation of Fracture Risk with Antidepressant Use by Class, Drug, and Indication. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(7), 1494–1503. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16404

- Sundaresh, V., & Singh, B. (2020). Antidepressants and Fracture Risk: Is There a Real Connection? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(9), 2141–2142. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16729

- Lassen, D., Ennis, Z. N., & Damkier, P. (2016). First-Trimester Pregnancy Exposure to Venlafaxine or Duloxetine and Risk of Major Congenital Malformations: A Systematic Review. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 118(1), 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.12497

- Huybrechts, K. F., Bateman, B. T., Pawar, A., Bessette, L. G., Mogun, H., Levin, R., Li, H., Motsko, S., Scantamburlo Fernandes, M. F., Upadhyaya, H. P., & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2020). Maternal and fetal outcomes following exposure to duloxetine in pregnancy: Cohort study. BMJ, m237. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m237

- Jiang, H., Xu, L., Li, Y., Deng, M., Peng, C., & Ruan, B. (2016). Antidepressant use during pregnancy and risk of postpartum hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 83, 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.001

- Boyce, P. M., Hackett, L. P., & Ilett, K. F. (2011). Duloxetine transfer across the placenta during pregnancy and into milk during lactation. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 14(2), 169–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0215-5

- Sriraman, N. K., Melvin, K., Meltzer-Brody, S., & the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. (2015). ABM Clinical Protocol #18: Use of Antidepressants in Breastfeeding Mothers. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(6), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.29002

- MacQueen, G. M., Frey, B. N., Ismail, Z., Jaworska, N., Steiner, M., Lieshout, R. J. V., Kennedy, S. H., Lam, R. W., Milev, R. V., Parikh, S. V., Ravindran, A. V., & CANMAT Depression Work Group. (2016). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 6. Special Populations: Youth, Women, and the Elderly. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 61(9), 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716659276

- Grzeskowiak, L. E., Saha, M. R., Nordeng, H., Ystrom, E., & Amir, L. H. (2022). Perinatal antidepressant use and breastfeeding outcomes: Findings from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 101(3), 344. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14324

- Duloxetine. (2024). In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK501470/

- Use of Duloxetine in Pregnancy and Lactation – Gerald G Briggs, Peter J Ambrose, Kenneth F llett, L Peter Hackett, Michael P Nageotte, Guadalupe Padilla, 2009. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2024, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1345/aph.1M317?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

- Treatment and Management of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 5. (2023). Obstetrics and Gynecology, 141(6), 1262–1288. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000005202