In a nutshell

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic with rapid-acting antidepressant properties that has gained significant attention in psychiatric practice over the past decade. Like esketamine, it delivers a very rapid antidepressant effect (within 40 min-24 h). Still, evidence for sustained benefit beyond a few weeks is limited, and all psychiatric uses remain off-label in the United States.

- Consider esketamine vs ketamine when:

- Insurance coverage is available

- Standardized protocols are preferred – REMS program provides structured safety monitoring and dosing guidelines.

- Legal protection is prioritized

- Patient prefers non-invasive administration

- Maintenance treatment is planned – Superior evidence base for relapse prevention during maintenance phase

- Consider ketamine vs esketamine when:

- Rapid, robust response is needed – IV ketamine achieves remission faster than esketamine (hazard ratio = 5.0) [1]

- Cost is a primary concern and insurance coverage is unavailable

- Flexible dosing is required – Ability to adjust doses (0.5-1.0 mg/kg) based on individual response

- Clinical expertise exists – Established IV ketamine protocols and experienced clinical staff

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

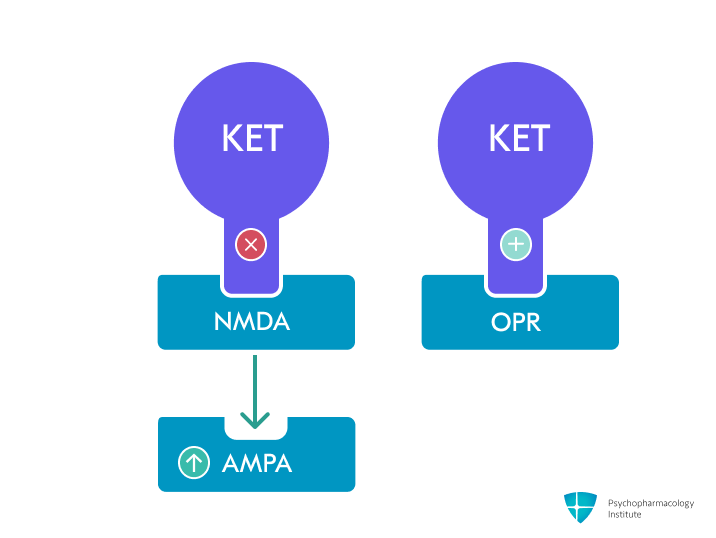

- Primary mechanism: Non-competitive, nonselective NMDA receptor antagonist [2–4]

- Racemic mixture containing equal parts of S-ketamine (esketamine) and R-ketamine enantiomers [5]

- Binds to phencyclidine (PCP) site within NMDA receptor channel pore, blocking glutamate-induced calcium influx [3]

- Preferentially inhibits NMDA receptors on GABAergic interneurons, causing disinhibition of pyramidal neurons and increased glutamate release [4]

- Enantiomer differences

- S-ketamine (esketamine) has 2-3 fold higher NMDA receptor affinity than R-ketamine [3,6,7]

- R-ketamine may have distinct properties, including potentially greater BDNF effects and fewer psychotomimetic effects in preclinical studies, though clinical significance remains under investigation [8]

- AMPA receptor modulation

-

Indirectly enhances AMPA receptor signaling through increased glutamate release [3]

-

Ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine directly activates AMPA receptors, contributing to antidepressant effects without NMDA antagonism [9]

-

This shift from NMDA to AMPA signaling appears critical for rapid antidepressant effects [4]

-

- Downstream effects on brain plasticity

- Increases BDNF release, potentially explaining rapid synaptogenic and antidepressant effects [3,4]

- Activates mTOR signaling pathway, leading to increased protein synthesis and dendritic spine formation in prefrontal cortex [10]

- Opioid receptors

- Clinical evidence suggests opioid system involvement: naltrexone pretreatment significantly attenuated ketamine’s antidepressant effects in humans [11]

- Binds to μ-, κ-, and δ-opioid receptors with Ki values of 42.1, 28.1, and 272 μM respectively [3,4,11]

- Contribution to therapeutic effects remains debated, with conflicting evidence from naltrexone studies and genetic analyses [4,11,12]

- May explain why other NMDA antagonists (e.g., memantine) lack antidepressant efficacy [13,14]

- Additional pharmacological targets

- Sigma receptors: R-ketamine shows higher σ1 receptor affinity than S-ketamine; racemic ketamine preferentially binds σ2 receptors, potentially modulating neuroplasticity pathways [3]

- Other targets: Weak inhibition of monoamine transporters (SERT, NET, DAT), antagonism at 5-HT3 and nicotinic receptors, and weak D2 receptor agonism at subanesthetic doses [3,4]

Pharmacokinetics and Interactions

Metabolism and pharmacokinetic interactions

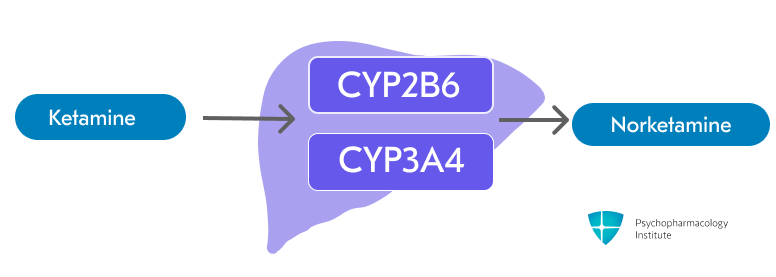

- Ketamine is primarily metabolized through N-dealkylation via CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 to form the active metabolite Norketamine [2,3]

- Minor pathways involve CYP2C9 and other CYP enzymes [3]

- Norketamine has approximately one-third the anesthetic potency of ketamine [2]

-

Ketamine levels potentially increased by:

- Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors:

- Ketoconazole, clarithromycin [15]

- Grapefruit juice [16,17]

- CYP2B6 inhibitors:

- Fluvoxamine, ticlopidine, orphenadrine [15,18]

- Monitor for evidence of increased ketamine effects and consider dose reduction

- Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors:

-

Ketamine levels potentially decreased by:

- Strong CYP3A4 inducers:

- Rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin, St. John’s Wort [15]

- Monitor for reduced efficacy; dose increase may be necessary

- CYP2B6 inducers:

- Rifampin, efavirenz, nevirapine, phenobarbital

- Monitor for signs of reduced ketamine efficacy

- Strong CYP3A4 inducers:

-

CYP2B6 polymorphisms:

- The CYP2B6*6 allele (15-60% frequency, highest in African and Asian populations) reduces enzyme activity

- May require lower ketamine doses in homozygous carriers [15]

- Clinical significance unclear due to conflicting study results [15,19]

-

Oral route is less reliable than parenteral administration

- Bioavailability only 20-30% due to extensive first-pass metabolism [20]

- Results in higher norketamine:ketamine ratios and less predictable dosing

Pharmacodynamic interactions

- Drug interactions

- CNS depressants(benzodiazepines, opioids, alcohol)

- May result in profound sedation, respiratory depression, coma, and death [2]

- Closely monitor respiratory parameters and consider dose reductions

- Opioid analgesics may prolong recovery time [2]

- Benzodiazepines and antidepressant efficacy

- May diminish antidepressant benefits of ketamine [21,22]

- Clinical reports suggest delayed response, earlier relapse with concurrent benzodiazepine use [23]

- Possible mechanisms: GABA-mediated CNS depression or suppression of ketamine-induced glutamatergic signaling [15]

- Theophylline/Aminophylline

- Concomitant use may lower seizure threshold [2]

- Consider alternative to ketamine in patients receiving these medications

- Sympathomimetics and vasopressin:

- May enhance ketamine’s sympathomimetic effects [2]

- Monitor vital signs closely and consider individualized dose adjustments

- Glutamatergic modulators:

- Lamotrigine: May reduce some of ketamine’s effects, but unknown impact on antidepressant efficacy [15]

- Memantine: theoretical antagonism of ketamine effects through NMDA receptor competition [15,24]

- Clozapine: may theoretically influence glutamatergic neurotransmission through action on glycine transporters, blunting effects of ketamine [15,25,26]

- Use caution until formal studies clarify impact on therapeutic benefits

- MAOIs:

- Recent systematic review suggests combination may be safer than previously thought [27]

- No cases of hypertensive crisis or serotonin syndrome reported

- Blood pressure and heart rate increases were clinically insignificant in all but one patient

- Traditional concerns about hypertensive reactions remain; further research needed

- Monitor cardiovascular parameters closely if combination is considered necessary

- CNS depressants(benzodiazepines, opioids, alcohol)

Half-life

- Ketamine has a biphasic elimination pattern:

- Alpha phase (anesthetic effect): 10-15 minutes – rapid onset and offset of anesthetic effects [2]

- Beta phase (redistribution): 2.5 hours – reflects redistribution from CNS to peripheral tissues [2]

- Effects typically last 1-2 hours for IV administration and 3-4 hours for IM administration

Dosage forms

Dosage forms

- Immediate-release:

- Injectable solution (IV/IM, multiple-dose vials)

- 10 mg/mL (200 mg/20 mL), 50 mg/mL (500 mg/10 mL), 100 mg/mL (500 mg/5 mL)

- Ketalar, Generic

- Intranasal solution (compounded, off-label)

- Variable concentrations (typically prepared from 50 mg/mL or 100 mg/mL injectable solutions)

- Compounded preparations

- Oral solution (compounded, off-label)

- Variable concentrations (prepared from injectable solutions for weight-based dosing)

- Compounded preparations

- Injectable solution (IV/IM, multiple-dose vials)

- Formulation considerations:

- Injectable solutions

- IM administration requires deep injection into large muscle mass

- IV bolus doses should be administered over 1 minute (0.5 mg/kg/minute); depression treatment requires a 40-minute infusion [28]

- Off-label preparations:

- Intranasal: Volume limitations restrict adequate adult dosing.

- Oral: Injectable solution may be administered undiluted or mixed with flavoring agents; administer immediately after preparation.

- Other routes (subcutaneous, rectal) exist but are not used in psychiatric practice

- Investigational formulations:

- Preservative-free formulations (NRX-100) aim to eliminate benzethonium chloride found in current preparations

- pH-neutral formulations (HTX-100) designed for both IV and subcutaneous administration

- Extended-release oral tablets (R-107) being studied to minimize dissociative effects and enable potential at-home use

- Injectable solutions

Indications

Psychiatric off-label uses

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD)

-

Ketamine may be considered for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) who have not responded to other antidepressant therapies.

- Note: Esketamine (intranasal) is an FDA-approved formulation for TRD and MDD with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) [29]

- Ketamine provides rapid antidepressant effects within hours (vs. weeks for traditional antidepressants) [30–32]

- IV ketamine appears as a viable option for patients with acute suicidality or who need ultra-rapid antidepressant response [33]

-

Efficacy evidence:

- Single IV infusion produces a rapid response beginning at 40 min and peaking at 24 hours [34,35]

- Response typically diminishes by day 10-14 without maintenance treatment [13].

- Relapse rates up to 90% at four weeks following a single treatment [34]

- May be as effective as ECT for treatment-resistant cases according to recent trials [36]

- Repeated infusions (2-3 times weekly) may sustain antidepressant effects [31]

- Onset of antidepressant effect may perhaps be faster with repeated infusions of ketamine, compared with repeated treatments with ECT [37]

- Ketamine showed the largest improvement at two weeks compared to other treatments such as medications, ECT, and rTMS in treatment-resistant depression [38]

- Treatment duration up to 6 weeks has been studied, though optimal length of therapy and maintenance dosing protocols remain to be established [39]

- Long-term ketamine efficacy and safety remain largely unknown due to limited high-quality studies with short treatment durations and inadequate follow-up [40,41]

- Sparse observational data show variable responses and high relapse rates, raising concerns about tolerance, tachyphylaxis, and potential dependence with repeated use [28,42–44]

-

Ketamine as augmentation

- Ketamine can be safely combined with most standard antidepressants. Randomized trials support its use both as monotherapy and as add-on therapy to antidepressants and antipsychotics [30]

- May accelerate antidepressant response when combined with conventional therapy

- One trial found higher response rates and faster improvement when ketamine was added to escitalopram [45]

-

Dosing:

- Intravenous (IV) route (most studied)

- Initial: 0.5 mg/kg (less than the dose used for inducing general anesthesia) administered over 40 minutes [46,47]

- May increase to 0.75-1 mg/kg based on response and tolerability [48]

- Obesity adjustment: Use ideal body weight for BMI ≥30 kg/m² to reduce cardiovascular risks [49]

- Infusion rate: Standard 40 minutes, though rates have varied from 2-100 minutes across studies; slower rates may reduce adverse effects [48]

- Frequency: Initially 2-3 times weekly, then once weekly or biweekly for maintenance [39]

- Intramuscular (IM) route

- Initial: 0.25-0.5 mg/kg/dose [50]

- Comparable efficacy to IV route in small head-to-head studies [50]

- May be preferred when IV access is difficult or for outpatient settings [51]

- Additional doses described, but frequency and dosing poorly defined [51]

- Intranasal route (limited evidence):

- Can be prescribed in an intranasal formulation from compounding pharmacies.

- 50 mg demonstrated efficacy in one small randomized crossover trial [52]

- Oral route (limited evidence):

- 1 mg/kg thrice weekly showed benefit over placebo in small RCT [53]

- Bioavailability only 20-30% due to extensive first-pass metabolism [54]

- Currently available formulations taste poorly and have limited duration [30]

- Investigational extended-release formulation: Phase 2 study showed promise with twice weekly dosing, designed to mitigate abuse concerns [55]

- Intravenous (IV) route (most studied)

Acute suicidal ideation

- Rapid antisuicidal effects reported in multiple randomized controlled trials [33]

- Meta-analysis shows a significant reduction in suicidal ideation compared to placebo within 24 hours, lasting up to 7 days [56]

- Can provide a crucial therapeutic window during acute crisis while conventional antidepressants take effect [33]

- Effective in both unipolar and bipolar depression with suicidal ideation [57]

- Dosing:

- Similar to TRD dosing:

- IV: 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes [57]

- May consider more frequent initial dosing (e.g., 2-3 times in first week) for high-risk patients [39]

- Similar to TRD dosing:

Bipolar depression

- Has been studied and used as an adjunct to mood stabilizers rather than monotherapy [ [58];Bahji2022a; [59]; [60]; [13]]

- Initial reduction in depressive symptoms up to 3-6 days, but no sustained superiority over controls from 7-13 days onward according to recent meta-analyses [29]

- Evidence quality is generally poor with low certainty, and insufficient data to differentiate racemic ketamine from esketamine effects [29]

- No clear benefit for remission/response rates in bipolar-only analyses beyond the acute phase, further research needed [ [29]; Bahji2022a]

- Dosing:

- Similar to TRD dosing with careful monitoring:

- IV: 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes [59]

- Consider concurrent mood stabilizer therapy to prevent mood switching [13]

- Similar to TRD dosing with careful monitoring:

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline suggests against the use of ketamine for the treatment of PTSD [61]

- Significant improvement in PTSD symptoms at 24 hours and 1-4 week endpoints with small to moderate effect size (standardized effect = 0.25) [62]

- However, high heterogeneity across studies and methodological quality concerns limit the certainty of findings [62,63]

- Anxiolytic effects across acute (<12h), subacute (24h), and sustained (7-14 days) timepoints [63]

- Evidence suggests potential for both rapid symptom relief and sustained neuroplastic changes [64]

- May be helpful for comorbid PTSD and depression [65]

- Dosing:

- Limited data, generally follows TRD dosing:

- IV: 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes [66]

- Limited data, generally follows TRD dosing:

FDA-approved Indications

General anesthesia (induction ± maintenance)

- Intravenous or intramuscular dissociative anesthetic used as a sole agent, for induction before other agents, or as a supplement when hemodynamic stability is desirable [2]

- Used as an adjunct to decrease the need for other anesthetic medications. Particularly valuable in opioid-tolerant patients to minimize opioid requirements.

- Dosing

- Anesthetic doses (2-4.5 mg/kg IV) are approximately 4-10x higher than doses used for depression [2]

Side Effects

Most common side effects

Neurological/Psychiatric

- Dissociation and psychotomimetic effects (>70% of patients) [67]

- It may occur more often with ketamine than with esketamine. However, no head-to-head trials comparing the two drugs have been published [68]

- Most common adverse effect and primary reason for treatment discontinuation [2,67]

- Includes transient perceptual changes, depersonalization, derealization, hallucinations, and emergence reactions

- Typically begins during infusion and resolves within 2-4 hours [2,13]

- May manifest as pleasant dream-like states to frank delirium and irrational behavior [2]

- Intensity tends to diminish with repeated administrations [31]

- Emergence reactions (12% incidence)

- Postoperative confusional states, agitation, and vivid imagery during recovery period [2]

- Duration generally a few hours, with no known residual psychological effects from anesthetic use

- Higher incidence with intravenous administration and higher doses

- Can be reduced by minimizing verbal, tactile, and visual stimulation during recovery [2]

- Anxiety, blurred vision, poor coordination

- Headache

- Nausea or vomiting

Cardiovascular

- Blood pressure elevation (frequently observed) (30-40% incidence) [67]

- Typically occur 30-40 minutes post-infusion and resolve within 70-90 minutes [2]

- Systolic BP (20 mmHg average peak) [13,49,57,69]

- Diastolic BP (13 mmHg average peak) [49,57,69]

- Dose-dependent response with higher elevations at increased doses [70]

- Heart rate increase

- Mean increases of 9 beats/minute within 2 hours of infusion [69]

- Changes typically normalize within hours of administration

- Increased cardiac output and cardiac index [2]

- Results from ketamine’s sympathomimetic effects and catecholamine reuptake inhibition

- May increase myocardial oxygen demand

- Other effects: Chest pain, palpitations, and pressure may occur but typically resolve within 90 minutes [67]

Gastrointestinal

- Nausea and vomiting

- Common transient adverse effects in randomized trials [31,57]

- Generally resolve within hours of administration

Other common side effects

- Dizziness and coordination difficulties

- Increased salivation [2]

- Antisialagogue may be administered prior to induction to manage hypersalivation

- Diplopia and nystagmus [2]

- Elevation in intraocular pressure [2]

Severe side effects

- Respiratory depression and apnea

- May occur with overdosage or rapid rate of administration [2]

- Emergency airway equipment must be immediately available [2]

- Abuse and dependence potential

- Schedule III controlled substance due to abuse potential [2]

- The addictive potential of ketamine could be attributed to its chemical structure being similar to phencyclidine, as well as its agonistic effects on opioid receptors [67,71]

- Street Names: Special K, K, Kit Kat, Cat Valium, Super Acid, Special La Coke, Purple, Jet, and Vitamin K [67,72]

- Physical and psychological dependence may occur with prolonged use; tolerance may develop with repeated use.

- Renal and urinary disorders (with chronic use)

- Lower urinary tract symptoms, including dysuria, frequency, urgency, and hematuria [2]

- Cystitis and reduced bladder capacity have been reported with long-term off-label use

- Regular monitoring recommended for patients with a history of chronic ketamine use [2]

- Neurotoxicity (with long-term use)

- Studies in abusers show adverse effects on brain structure and cognitive function [67]

- Hepatotoxicity (with recurrent use)

- Drug-induced liver injury with cholestatic pattern [2]

- Baseline liver function tests recommended for patients receiving recurrent ketamine [2]

Contraindications

- Patients for whom significant elevation of blood pressure would constitute a serious hazard [2]

- Known hypersensitivity to ketamine or any component of the formulation [2]

- Known or suspected schizophrenia (absolute contraindication) [73]

Use in special populations

Pregnancy

- Not recommended: Animal studies show dose-dependent histopathologic changes in fetal organs and neurodevelopmental concerns [74,75]

- Fetal brain development may be affected through NMDA receptor antagonism.

Breastfeeding

- Ketamine and metabolites present in breast milk with relative infant dose 0.34-0.77% of maternal dose [76,77]

- Single-dose use (e.g., surgical procedures) generally considered acceptable with no reported adverse effects in breastfed infants [78,79]

- Repeated/chronic use for depression:

- Limited safety data available; case series of 4 patients showed no adverse effects [76]

- The manufacturer of Esketamine does not recommend breastfeeding during treatment since NMDA receptor antagonism affects rapid brain development in infants [80]

- Monitor breastfed infants for sedation, poor feeding, and adequate weight gain

Hepatic impairment

- No dosage adjustments are provided in the manufacturer’s labeling.

- Ketamine undergoes extensive metabolism in the liver.

- Hepatic impairment is expected to reduce the clearance of ketamine, leading to increased plasma concentrations and a prolonged elimination half-life.

- Hepatobiliary dysfunction has been reported with recurrent or prolonged use of ketamine (e.g., scenarios of misuse/abuse, or medically supervised but unapproved off-label indications such as certain chronic pain regimens) [2,81]

Renal impairment

- Mild to moderate impairment:

- No dose adjustment necessary for single doses [20]

- Severe impairment/End-stage renal disease:

- No dosage adjustment necessary [82]

- Use with caution. Avoid prolonged use or monitor for signs of toxicity

- Parenteral: Ketamine levels may be 20% higher; active metabolites may accumulate with unknown clinical significance [82,83]

- Oral administration (off-label): Limited pharmacokinetic data; extensive first-pass metabolism results in higher norketamine and dehydronorketamine concentrations compared to parenteral routes [54,84]

Obesity

- Limited data. Inconsistent dosing strategies prevent universal weight-based recommendations [85,86]

- Class 1 and 2 obesity (BMI 30-39 kg/m²):

- Use actual body weight for initial dosing

- Titrate to clinical effect as needed

- Class 3 obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m²):

- Use adjusted body weight or ideal body weight for initial dosing [87]

- Maintain consistent dosing weight throughout therapy (do not switch between weight calculations). Monitor for metabolite accumulation with prolonged use.

Elderly

- No specific dose adjustments needed

- Older adults metabolize ketamine slowly and need lower dosing.

Brand names

- US: Ketalar

- Canada: Ketalar

- Other countries/regions: Calypsol, Inducmina, Kain, Keiran, Ketalar, Ketanest, Ketamin, Ketamin curamed, Ketamin Inresa, Ketamin sintetica, Ketamine, Ketamine HCL, Ketamine interpharma, Ketlar, Ketomin, Micro ketamine, Narkamon, Tekam

References

- Singh, B., Kung, S., Pazdernik, V., Schak, K. M., Geske, J., Schulte, P. J., Frye, M. A., & Vande Voort, J. L. (2023). Comparative Effectiveness of Intravenous Ketamine and Intranasal Esketamine in Clinical Practice Among Patients With Treatment-Refractory Depression: An Observational Study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 84(2), 22m14548. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.22m14548

- Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (n.d.). KetalarFDA. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/016812s051lbl.pdf

- Zanos, P., Moaddel, R., Morris, P. J., Riggs, L. M., Highland, J. N., Georgiou, P., Pereira, E. F. R., Albuquerque, E. X., Thomas, C. J., Zarate, C. A., & Gould, T. D. (2018). Ketamine and Ketamine Metabolite Pharmacology: Insights into Therapeutic Mechanisms. Pharmacological Reviews, 70(3), 621–660. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.117.015198

- McIntyre, R. S., Rosenblat, J. D., Nemeroff, C. B., Sanacora, G., Murrough, J. W., Berk, M., Brietzke, E., Dodd, S., Gorwood, P., Ho, R., Iosifescu, D. V., Lopez Jaramillo, C., Kasper, S., Kratiuk, K., Lee, J. G., Lee, Y., Lui, L. M. W., Mansur, R. B., Papakostas, G. I., … Stahl, S. (2021). Synthesizing the Evidence for Ketamine and Esketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression: An International Expert Opinion on the Available Evidence and Implementation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(5), 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20081251

- Jelen, L. A., Young, A. H., & Stone, J. M. (2021). Ketamine: A tale of two enantiomers. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 35(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120959644

- Liu, P., Zhang, S.-S., Liang, Y., Gao, Z.-J., Gao, W., & Dong, B.-H. (2022). Efficacy and Safety of Esketamine Combined with Antidepressants for Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 18, 2855–2865. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S388764

- Vasiliu, O. (2023). Esketamine for treatment‑resistant depression: A review of clinical evidence (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 25(3), 111. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2023.11810

- Yang, C., Shirayama, Y., Zhang, J., Ren, Q., Yao, W., Ma, M., Dong, C., & Hashimoto, K. (2015). R-ketamine: A rapid-onset and sustained antidepressant without psychotomimetic side effects. Translational Psychiatry, 5(9), e632. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.136

- Zanos, P., Moaddel, R., Morris, P. J., Georgiou, P., Fischell, J., Elmer, G. I., Alkondon, M., Yuan, P., Pribut, H. J., Singh, N. S., Dossou, K. S. S., Fang, Y., Huang, X.-P., Mayo, C. L., Wainer, I. W., Albuquerque, E. X., Thompson, S. M., Thomas, C. J., Zarate, C. A., & Gould, T. D. (2016). NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature, 533(7604), 481–486. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17998

- Duman, R. S., Aghajanian, G. K., Sanacora, G., & Krystal, J. H. (2016). Synaptic plasticity and depression: New insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nature Medicine, 22(3), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4050

- Williams, N. R., Heifets, B. D., Blasey, C., Sudheimer, K., Pannu, J., Pankow, H., Hawkins, J., Birnbaum, J., Lyons, D. M., Rodriguez, C. I., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2018). Attenuation of Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine by Opioid Receptor Antagonism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(12), 1205–1215. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020138

- Sanacora, G. (2019). Caution Against Overinterpreting Opiate Receptor Stimulation as Mediating Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 176(3), 249. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18091061

- Newport, D. J., Carpenter, L. L., McDonald, W. M., Potash, J. B., Tohen, M., Nemeroff, C. B., & APA Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. (2015). Ketamine and Other NMDA Antagonists: Early Clinical Trials and Possible Mechanisms in Depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(10), 950–966. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040465

- Ates-Alagoz, Z., & Adejare, A. (2013). NMDA Receptor Antagonists for Treatment of Depression. Pharmaceuticals, 6(4), 480–499. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph6040480

- Andrade, C. (2017). Ketamine for Depression, 4: In What Dose, at What Rate, by What Route, for How Long, and at What Frequency? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(7), e852–e857. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17f11738

- Bailey, D. G., Dresser, G., & Arnold, J. M. O. (2013). Grapefruit-medication interactions: Forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences? CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne, 185(4), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.120951

- Peltoniemi, M. A., Saari, T. I., Hagelberg, N. M., Laine, K., Neuvonen, P. J., & Olkkola, K. T. (2012). S-ketamine concentrations are greatly increased by grapefruit juice. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 68(6), 979–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1214-9

- Peltoniemi, M. A., Saari, T. I., Hagelberg, N. M., Reponen, P., Turpeinen, M., Laine, K., Neuvonen, P. J., & Olkkola, K. T. (2011). Exposure to oral S-ketamine is unaffected by itraconazole but greatly increased by ticlopidine. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 90(2), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2011.140

- Rao, L. K., Flaker, A. M., Friedel, C. C., & Kharasch, E. D. (2016). Role of Cytochrome P4502B6 Polymorphisms in Ketamine Metabolism and Clearance. Anesthesiology, 125(6), 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001392

- Mion, G., & Villevieille, T. (2013). Ketamine Pharmacology: An Update (Pharmacodynamics and Molecular Aspects, Recent Findings). CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 19(6), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12099

- Ford, N., Ludbrook, G., & Galletly, C. (2015). Benzodiazepines may reduce the effectiveness of ketamine in the treatment of depression. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(12), 1227–1227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415590631

- Frye, M. A., Blier, P., & Tye, S. J. (2015). Concomitant benzodiazepine use attenuates ketamine response: Implications for large scale study design and clinical development. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 35(3), 334–336. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000316

- Albott, C. S., Shiroma, P. R., Cullen, K. R., Johns, B., Thuras, P., Wels, J., & Lim, K. O. (2017). The Antidepressant Effect of Repeat Dose Intravenous Ketamine Is Delayed by Concurrent Benzodiazepine Use. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(3), e308–e309. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16l11277

- Uribe, E., Landaeta, J., Wix, R., & Eblen, A. (2013). Memantine Reverses Social Withdrawal Induced by Ketamine in Rats. Experimental Neurobiology, 22(1), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.5607/en.2013.22.1.18

- Javitt, D. C. (2004). Glutamate as a therapeutic target in psychiatric disorders. Molecular Psychiatry, 9(11), 984–997, 979. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4001551

- Malhotra, A. K., Adler, C. M., Kennison, S. D., Elman, I., Pickar, D., & Breier, A. (1997). Clozapine blunts N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist-induced psychosis: A study with ketamine. Biological Psychiatry, 42(8), 664–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00546-x

- Veraart, J. K. E., Smith-Apeldoorn, S. Y., Kutscher, M., Vischjager, M., Meij, A. van der, Kamphuis, J., & Schoevers, R. A. (2022). Safety of Ketamine Augmentation to Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Systematic Literature Review and Case Series. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 83(6), 21m14267. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21m14267

- Sanacora, G., Frye, M. A., McDonald, W., Mathew, S. J., Turner, M. S., Schatzberg, A. F., Summergrad, P., Nemeroff, C. B., & for the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. (2017). A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(4), 399. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0080

- Rodolico, A., Cutrufelli, P., Di Francesco, A., Aguglia, A., Catania, G., Concerto, C., Cuomo, A., Fagiolini, A., Lanza, G., Mineo, L., Natale, A., Rapisarda, L., Petralia, A., Signorelli, M. S., & Aguglia, E. (2024). Efficacy and safety of ketamine and esketamine for unipolar and bipolar depression: An overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1325399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1325399

- Andrade, C. (2017). Ketamine for Depression, 5: Potential Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug Interactions: (Clinical and Practical Psychopharmacology). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(7), e858–e861. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17f11802

- Singh, J. B., Fedgchin, M., Daly, E. J., De Boer, P., Cooper, K., Lim, P., Pinter, C., Murrough, J. W., Sanacora, G., Shelton, R. C., Kurian, B., Winokur, A., Fava, M., Manji, H., Drevets, W. C., & Van Nueten, L. (2016). A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Frequency Study of Intravenous Ketamine in Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(8), 816–826. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010037

- Kryst, J., Kawalec, P., Mitoraj, A. M., Pilc, A., Lasoń, W., & Brzostek, T. (2020). Efficacy of single and repeated administration of ketamine in unipolar and bipolar depression: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Pharmacological Reports, 72(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-020-00097-z

- Wilkinson, S. T., Katz, R. B., Toprak, M., Webler, R., Ostroff, R. B., & Sanacora, G. (2018). Acute and longer-term outcomes using ketamine as a clinical treatment at the Yale Psychiatric Hospital. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(4), 17m11731. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17m11731

- Kishimoto, T., Chawla, J. M., Hagi, K., Zarate, C. A., Kane, J. M., Bauer, M., & Correll, C. U. (2016). Single-dose infusion ketamine and non-ketamine N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists for unipolar and bipolar depression: A meta-analysis of efficacy, safety and time trajectories. Psychological Medicine, 46(7), 1459–1472. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716000064

- McGirr, A., Berlim, M. T., Bond, D. J., Fleck, M. P., Yatham, L. N., & Lam, R. W. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive episodes. Psychological Medicine, 45(4), 693–704. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714001603

- Anand, A., Mathew, S. J., Sanacora, G., Murrough, J. W., Goes, F. S., Altinay, M., Aloysi, A. S., Asghar-Ali, A. A., Barnett, B. S., Chang, L. C., Collins, K. A., Costi, S., Iqbal, S., Jha, M. K., Krishnan, K., Malone, D. A., Nikayin, S., Nissen, S. E., Ostroff, R. B., … Hu, B. (2023). Ketamine versus ECT for Nonpsychotic Treatment-Resistant Major Depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(25), 2315–2325. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2302399

- Ghasemi, M., Kazemi, M. H., Yoosefi, A., Ghasemi, A., Paragomi, P., Amini, H., & Afzali, M. H. (2014). Rapid antidepressant effects of repeated doses of ketamine compared with electroconvulsive therapy in hospitalized patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research, 215(2), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.008

- Papadimitropoulou, K., Vossen, C., Karabis, A., Donatti, C., & Kubitz, N. (2017). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological and somatic interventions in adult patients with treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 33(4), 701–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2016.1277201

- Phillips, J. L., Norris, S., Talbot, J., Hatchard, T., Ortiz, A., Birmingham, M., Owoeye, O., Batten, L. A., & Blier, P. (2020). Single and repeated ketamine infusions for reduction of suicidal ideation in treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(4), 606–612. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0570-x

- Sanacora, G., Frye, M. A., McDonald, W., Mathew, S. J., Turner, M. S., Schatzberg, A. F., Summergrad, P., Nemeroff, C. B., & American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. (2017). A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(4), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0080

- Schatzberg, A. F. (2014). A Word to the Wise About Ketamine. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 262–264. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101434

- Freedman, R., Brown, A. S., Cannon, T. D., Druss, B. G., Earls, F. J., Escobar, J., Hurd, Y. L., Lewis, D. A., López-Jaramillo, C., Luby, J., Mayberg, H. S., Moffitt, T. E., Oquendo, M., Perlis, R. H., Pine, D. S., Rush, A. J., Tamminga, C. A., Tohen, M., Vieta, E., … Xin, Y. (2018). Can a Framework Be Established for the Safe Use of Ketamine? American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(7), 587–589. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18030290

- Szymkowicz, S. M., Finnegan, N., & Dale, R. M. (2013). A 12-month naturalistic observation of three patients receiving repeat intravenous ketamine infusions for their treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(0), 416–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.015

- Wilkinson, S. T., Ballard, E. D., Bloch, M. H., Mathew, S. J., Murrough, J. W., Feder, A., Sos, P., Wang, G., Zarate, C. A., & Sanacora, G. (2018). The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(2), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472

- Hu, Y.-D., Xiang, Y.-T., Fang, J.-X., Zu, S., Sha, S., Shi, H., Ungvari, G. S., Correll, C. U., Chiu, H. F. K., Xue, Y., Tian, T.-F., Wu, A.-S., Ma, X., & Wang, G. (2016). Single i.v. Ketamine augmentation of newly initiated escitalopram for major depression: Results from a randomized, placebo-controlled 4-week study. Psychological Medicine, 46(3), 623–635. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002159

- aan het Rot, M., Collins, K. A., Murrough, J. W., Perez, A. M., Reich, D. L., Charney, D. S., & Mathew, S. J. (2010). Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry, 67(2), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.038

- Murrough, J. W., Perez, A. M., Pillemer, S., Stern, J., Parides, M. K., aan het Rot, M., Collins, K. A., Mathew, S. J., Charney, D. S., & Iosifescu, D. V. (2013). Rapid and Longer-Term Antidepressant Effects of Repeated Ketamine Infusions in Treatment-Resistant Major Depression. Biological Psychiatry, 74(4), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.022

- Andrade, C. (2017). Ketamine for Depression, 3: Does Chirality Matter? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(6), e674–e677. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17f11681

- Wan, L.-B., Levitch, C. F., Perez, A. M., Brallier, J. W., Iosifescu, D. V., Chang, L. C., Foulkes, A., Mathew, S. J., Charney, D. S., & Murrough, J. W. (2015). Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(3), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08852

- Chilukuri, H., Reddy, N. P., Pathapati, R. M., Manu, A. N., Jollu, S., & Shaik, A. B. (2014). Acute antidepressant effects of intramuscular versus intravenous ketamine. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 36(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.127258

- Loo, C. K., Gálvez, V., O’Keefe, E., Mitchell, P. B., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Leyden, J., Harper, S., Somogyi, A. A., Lai, R., Weickert, C. S., & Glue, P. (2016). Placebo-controlled pilot trial testing dose titration and intravenous, intramuscular and subcutaneous routes for ketamine in depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 134(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12572

- Lapidus, K. A. B., Levitch, C. F., Perez, A. M., Brallier, J. W., Parides, M. K., Soleimani, L., Feder, A., Iosifescu, D. V., Charney, D. S., & Murrough, J. W. (2014). A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intranasal Ketamine in Major Depressive Disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 76(12), 970–976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.026

- Domany, Y., Bleich-Cohen, M., Tarrasch, R., Meidan, R., Litvak-Lazar, O., Stoppleman, N., Schreiber, S., Bloch, M., Hendler, T., & Sharon, H. (2019). Repeated oral ketamine for out-patient treatment of resistant depression: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 214(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.196

- Grant, I. S., Nimmo, W. S., & Clements, J. A. (1981). Pharmacokinetics and analgesic effects of i.m. And oral ketamine. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 53(8), 805–810. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/53.8.805

- Glue, P., Loo, C., Fam, J., Lane, H.-Y., Young, A. H., & Surman, P. (2024). Extended-release ketamine tablets for treatment-resistant depression: A randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Nature Medicine, 30(7), 2004–2009. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03063-x

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Chen-Li, D., Rosenblat, J. D., Rodrigues, N. B., Carvalho, I., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Narsi, F., Mansur, R. B., Lee, Y., & McIntyre, R. S. (2021). The acute antisuicidal effects of single-dose intravenous ketamine and intranasal esketamine in individuals with major depression and bipolar disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134, 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.038

- Grunebaum, M. F., Galfalvy, H. C., Choo, T.-H., Keilp, J. G., Moitra, V. K., Parris, M. S., Marver, J. E., Burke, A. K., Milak, M. S., Sublette, M. E., Oquendo, M. A., & Mann, J. J. (2018). Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: A midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(4), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17060647

- Fancy, F., Haikazian, S., Johnson, D. E., Chen-Li, D. C. J., Levinta, A., Husain, M. I., Mansur, R. B., & Rosenblat, J. D. (2023). Ketamine for bipolar depression: An updated systematic review. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 13, 20451253231202723. https://doi.org/10.1177/20451253231202723

- Zarate, C. A., Brutsche, N. E., Ibrahim, L., Franco-Chaves, J., Diazgranados, N., Cravchik, A., Selter, J., Marquardt, C. A., Liberty, V., & Luckenbaugh, D. A. (2012). Replication of Ketamine’s Antidepressant Efficacy in Bipolar Depression: A Randomized Controlled Add-on Trial. Biological Psychiatry, 71(11), 939–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.010

- Diazgranados, N., Ibrahim, L., Brutsche, N. E., Newberg, A., Kronstein, P., Khalife, S., Kammerer, W. A., Quezado, Z., Luckenbaugh, D. A., Salvadore, G., Machado-Vieira, R., Manji, H. K., & Zarate, C. A. (2010). A Randomized Add-on Trial of an N-methyl-d-aspartate Antagonist in Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(8), 793–802. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.90

- Schnurr, P. P., Hamblen, J. L., Wolf, J., Coller, R., Collie, C., Fuller, M. A., Holtzheimer, P. E., Kelly, U., Lang, A. J., McGraw, K., Morganstein, J. C., Norman, S. B., Papke, K., Petrakis, I., Riggs, D., Sall, J. A., Shiner, B., Wiechers, I., & Kelber, M. S. (2024). The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder: Synopsis of the 2023 U.s. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.s. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med., 177(3), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-2757

- Almeida, T. M., Lacerda da Silva, U. R., Pereira Pires, J., Neri Borges, I., Muniz Martins, C. R., Cordeiro, Q., & Uchida, R. R. (2024). EFFECTIVENESS OF KETAMINE FOR THE TREATMENT OF POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER – A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 21(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20240102

- Hartland, H., Mahdavi, K., Jelen, L. A., Strawbridge, R., Young, A. H., & Alexander, L. (2023). A transdiagnostic systematic review and meta-analysis of ketamine’s anxiolytic effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 37(8), 764–774. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811231161627

- Wellington, N. J., Boųcas, A. P., Lagopoulos, J., Quigley, B. L., & Kuballa, A. V. (2025). Molecular pathways of ketamine: A systematic review of immediate and sustained effects on PTSD. Psychopharmacology, 242(6), 1197–1243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-025-06756-4

- Pradhan, B., Kluewer D’Amico, J., Makani, R., & Parikh, T. (2016). Nonconventional interventions for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: Ketamine, repetitive trans-cranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), and alternative approaches. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 17(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.1046101

- Feder, A., Parides, M. K., Murrough, J. W., Perez, A. M., Morgan, J. E., Saxena, S., Kirkwood, K., Aan Het Rot, M., Lapidus, K. A. B., Wan, L.-B., Iosifescu, D., & Charney, D. S. (2014). Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(6), 681–688. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.62

- Short, B., Fong, J., Galvez, V., Shelker, W., & Loo, C. K. (2018). Side-effects associated with ketamine use in depression: A systematic review. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 5(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30272-9

- Andrade, C. (2017). Ketamine for Depression, 4: In What Dose, at What Rate, by What Route, for How Long, and at What Frequency?: The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(7), e852–e857. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17f11738

- Su, T.-P., Chen, M.-H., Li, C.-T., Lin, W.-C., Hong, C.-J., Gueorguieva, R., Tu, P.-C., Bai, Y.-M., Cheng, C.-M., & Krystal, J. H. (2017). Dose-Related Effects of Adjunctive Ketamine in Taiwanese Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(13), 2482–2492. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.94

- Fava, M., Freeman, M. P., Flynn, M., Judge, H., Hoeppner, B. B., Cusin, C., Ionescu, D. F., Mathew, S. J., Chang, L. C., Iosifescu, D. V., Murrough, J., Debattista, C., Schatzberg, A. F., Trivedi, M. H., Jha, M. K., Sanacora, G., Wilkinson, S. T., & Papakostas, G. I. (2020). Double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of intravenous ketamine as adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Molecular Psychiatry, 25(7), 1592–1603. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0256-5

- Malhi, G. S., Byrow, Y., Cassidy, F., Cipriani, A., Demyttenaere, K., Frye, M. A., Gitlin, M., Kennedy, S. H., Ketter, T. A., Lam, R. W., McShane, R., Mitchell, A. J., Ostacher, M. J., Rizvi, S. J., Thase, M. E., & Tohen, M. (2016). Ketamine: Stimulating antidepressant treatment? BJPsych Open, 2(3), e5–e9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.002923

- Administration, D. E. (2025). KETAMINE. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/ketamine.pdf

- Green, S. M., Roback, M. G., Kennedy, R. M., & Krauss, B. (2011). Clinical practice guideline for emergency department ketamine dissociative sedation: 2011 update. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 57(5), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.11.030

- Kochhar, M. M., Aykac, I., Davidson, P. P., & Fraley, E. D. (1986). Teratologic effects of d,1-2-(o-chlorophenyl)-2-(methylamino) cyclohexanone hydrochloride (ketamine hydrochloride) in rats. Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacology, 54(3), 413–416. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3797816

- Zhao, T., Li, Y., Wei, W., Savage, S., Zhou, L., & Ma, D. (2014). Ketamine administered to pregnant rats in the second trimester causes long-lasting behavioral disorders in offspring. Neurobiology of Disease, 68, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2014.02.009

- Majdinasab, E., Datta, P., Krutsch, K., Baker, T., & Hale, T. W. (2023–1 C.E.). Pharmacokinetics of Ketamine Transfer Into Human Milk. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 43(5), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001711

- Wolfson, P., Cole, R., Lynch, K., Yun, C., Wallach, J., Andries, J., & Whippo, M. (2023). The Pharmacokinetics of Ketamine in the Breast Milk of Lactating Women: Quantification of Ketamine and Metabolites. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 55(3), 354–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2022.2101903

- Mokube, J. A., Verla, V. S., Mbome, V. N., & Bitang, A. T. (2009). Burns in pregnancy: A case report from Buea Regional Hospital, Cameroon. The Pan African Medical Journal, 3, 21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2984292/

- Suppa, E., Valente, A., Catarci, S., Zanfini, B. A., & Draisci, G. (2012). A study of low-dose S-ketamine infusion as “preventive” pain treatment for cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: Benefits and side effects. Minerva Anestesiologica, 78(7), 774–781. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22374377

- Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (2025). SPRAVATO® esketamine hydrochloride solution Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. Prescribing Information.

- Noppers, I. M., Niesters, M., Aarts, L. P. H. J., Bauer, M. C. R., Drewes, A. M., Dahan, A., & Sarton, E. Y. (2011). Drug-induced liver injury following a repeated course of ketamine treatment for chronic pain in CRPS type 1 patients: A report of 3 cases. PAIN, 152(9), 2173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.03.026

- Köppel, C., Arndt, I., & Ibe, K. (1990). Effects of enzyme induction, renal and cardiac function on ketamine plasma kinetics in patients with ketamine long-term analgosedation. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 15(3), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03190213

- Schep, L. J., Slaughter, R. J., Watts, M., Mackenzie, E., & Gee, P. (2023). The clinical toxicology of ketamine. Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.), 61(6), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2023.2212125

- Weiss, M., & Siegmund, W. (2022). Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Ketamine Enantiomers and Their Metabolites After Administration of Prolonged-Release Ketamine With Emphasis on 2,6-Hydroxynorketamines. Clinical Pharmacology in Drug Development, 11(2), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpdd.993

- Adhikary, S. D., Thiruvenkatarajan, V., McFadden, A., Liu, W. M., Mets, B., & Rogers, A. (2021). Analgesic efficacy of ketamine and magnesium after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 68, 110097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110097

- Beaudequin, D., Can, A. T., Dutton, M., Jones, M., Gallay, C., Schwenn, P., Yang, C., Forsyth, G., Simcock, G., Hermens, D. F., & Lagopoulos, J. (2020). Predicting therapeutic response to oral ketamine for chronic suicidal ideation: A Bayesian network for clinical decision support. BMC Psychiatry, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02925-1

- Erstad, B. L., & Barletta, J. F. (2020). Drug dosing in the critically ill obese patient—a focus on sedation, analgesia, and delirium. Critical Care, 24(1), 315. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03040-z