In a nutshell

Mirtazapine enhances noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission through alpha-2 receptor antagonism and 5-HT2/5-HT3 receptor blockade. It is particularly suitable for depressed patients with insomnia, anxiety, or decreased appetite. Unlike SSRIs/SNRIs, mirtazapine causes minimal sexual dysfunction and GI side effects. Lower doses (≤15 mg) are more sedating than higher doses.

- Choosing mirtazapine over other antidepressants:

- Depression with prominent insomnia or poor appetite, given its H1 and 5-HT2/3 receptor blockade

- When sexual dysfunction is a concern (switching from SSRIs/SNRIs)

- For patients with poor appetite or weight loss

- When GI side effects limit SSRI/SNRI use

- Prefer alternatives if:

- Patients with obesity or metabolic syndrome

- Concern about sedation affecting daytime functioning

- Patients with hepatic impairment

- History of orthostatic hypotension

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

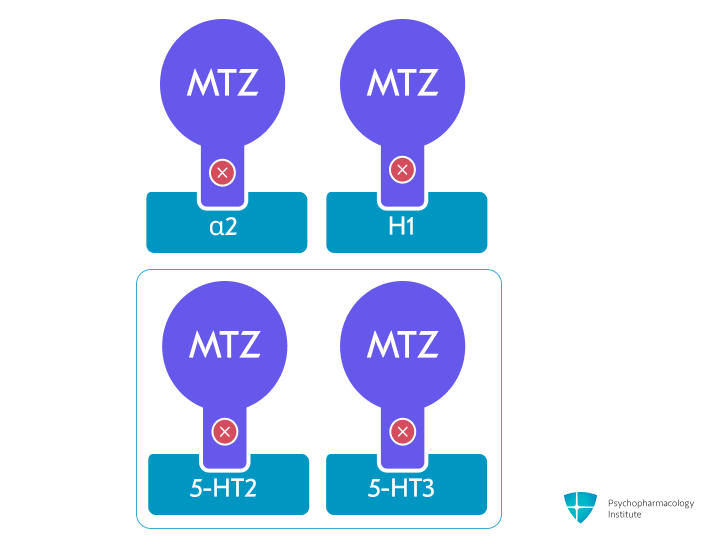

- Mirtazapine is a tetracyclic antidepressant that acts as an antagonist at central presynaptic α2-adrenergic autoreceptors and heteroreceptors [1]

- This mechanism enhances both noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission

- It has also been characterized as a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) [2]

- No direct serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibition

- Serotonergic effects:

- Potent antagonist at 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors [1,3]

- Mirtazapine increases noradrenergic and 5-HT1A-mediated serotonergic neurotransmission, despite showing no significant intrinsic affinity for 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors [1,4]

- This unique profile may explain its low rate of sexual dysfunction and GI side effects compared to SSRIs [5]

- Antihistaminergic effects:

- Potent H1 receptor antagonism [1,3,6]

- Shows inverse dose-response relationship with sedation – lower doses (≤15 mg) are more sedating than higher doses due to noradrenergic effects counteracting histamine blockade at higher doses [7–9]

- Additional receptor binding:

- Moderate antagonism at peripheral α1-adrenergic receptors [3]

- Weak muscarinic receptor antagonism [6]

- This may contribute to side effects like orthostatic hypotension and mild anticholinergic effects.

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism

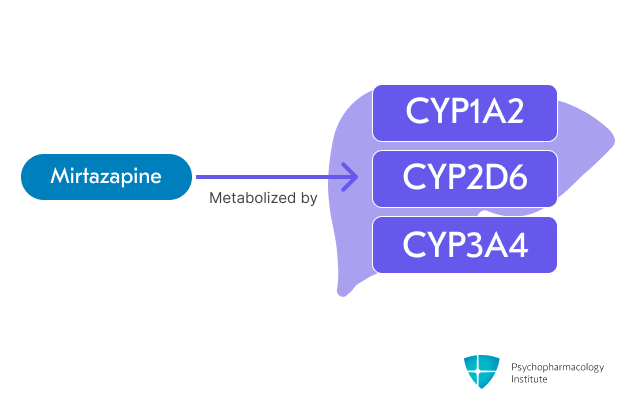

- Primarily metabolized through CYP1A2, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 [1,10]

- Mirtazapine levels potentially increased by:

- Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole): Increases peak plasma levels ~40% and AUC ~50% [1]

- Cimetidine (CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4 inhibitor): Increases AUC >50% [10]

- Consider decreasing mirtazapine dose when using these inhibitors

- Mirtazapine levels potentially decreased by:

- Strong CYP3A4 inducers:

- Carbamazepine: Decreases plasma concentrations ~60% [1]

- Phenytoin: Decreases plasma concentrations ~45% [1]

- Smoking: Reduces concentrations due to CYP1A2 induction [1]

- Consider increasing mirtazapine dose when using inducers and monitor therapy in patients who smoke

- Strong CYP3A4 inducers:

- Mirtazapine should be used cautiously with other QT-prolonging drugs like haloperidol, as concurrent use may increase the risk of QT interval prolongation.

- The concomitant use of warfarin with mirtazapine may result in increased INR [1]

- Monitor INR during concomitant use of warfarin

- Serotonergic agents:

- Concurrent use requires careful consideration.

- Monitor for serotonin syndrome with other serotonergic medications (SSRIs, SNRIs, triptans, tricyclic antidepressants)

- Also applies to tramadol, tryptophan, St. John’s Wort

- Contraindicated with MAOIs [11]

- A 14-day washout period is required after discontinuation before starting an MAOI

- A 14-day washout period is required after discontinuing an MAOI before initiating mirtazapine

Half-life

- Mirtazapine’s half-life is approximately 20-40 hours, with women exhibiting significantly longer elimination half-lives than men [10]

- The (–) enantiomer has an elimination half-life approximately twice as long as the (+) enantiomer [1]

Dosage forms

Dosage forms

- Immediate-release:

- Tablets

- 7.5 mg, 15 mg (scored), 30 mg (scored), 45 mg

- Generic, Remeron

- Orally disintegrating tablets

- 15 mg, 30 mg, 45 mg

- Generic, Remeron SolTab

- Formulation considerations

- Must remain in blister pack until ready to use

- Cannot be split or crushed

- Contains phenylalanine (component of aspartame)

- Tablets

Indications

FDA-Approved Indications

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

- First-line antidepressant treatment option for MDD [12,13]

- Particularly effective for depression with sleep disturbances and anxiety symptoms due to its unique receptor profile [6]

- May be a good option for patients with poor appetite or weight loss due to depression [6]

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 15 mg once daily at bedtime (due to sedating properties) [1]

- Sensitive patients: 7.5 mg daily in anxiety-prone patients [14]

- Increase dose in 15 mg increments at intervals of 1-2 weeks

- Target dose: 15-45 mg/day

- Maximum dose: 45 mg/day (though doses up to 60 mg have been studied) [15]

- Starting dose: 15 mg once daily at bedtime (due to sedating properties) [1]

Off-Label Uses

Panic Disorder

- Alternative agent for patients who are nonresponsive to SSRIs [16]

- Two open-label studies have shown efficacy in panic disorder [17,18]

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 15 mg once daily at bedtime

- Increase in 15 mg increments at ≥1 week intervals

- Target dose: 30 mg/day (average in clinical trials)

- Maximum dose: 45 mg once daily [19]

Sexual Dysfunction Associated with SSRIs

- Meta-analysis showed significantly lower rates compared to SSRIs [20] and other antidepressants [21]

- Two potential strategies for management:

- Strategy 1: Switch to mirtazapine

- Before switching, consider watchful waiting for 2-8 weeks, as sexual side effects may resolve spontaneously [21]

- When switching, use appropriate schedule (cross-taper over 1-2 weeks or immediate switch) [22]

- Initiate and titrate mirtazapine to therapeutic dose based on the primary indication

- Strategy 2: Add-on therapy

- Low-dose mirtazapine (15-30 mg/day) as an adjunct to ongoing SSRI treatment has shown effectiveness in reducing sexual dysfunction [23,24]

- Strategy 1: Switch to mirtazapine

Side Effects

Common side effects

- Somnolence (54% incidence)

- Most common side effect and cause of discontinuation, particularly at lower doses [1]

- Inverse dose-relationship: Lower doses (≤15 mg) cause more sedation than higher doses (>15 mg) [7,8]

- Mechanism: Primarily due to H1 antihistamine effects at lower doses; higher doses activate noradrenergic transmission which partially offsets sedation [7–9]

- Tolerance typically develops within a few days [25,26]

- Weight gain (12% incidence)

- Among antidepressants with the greatest impact on weight [27]

- Short-term (4-12 weeks): Average gain of 1.74 kg

- Long-term (≥4 months): Average gain of 2.59 kg

- Substantial long-term impact:

- 22% of patients experience >7% weight gain at 9 months [28]

- Highest risk among antidepressants in 10-year follow-up (rate ratio: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.45-1.56) [29]

- Mechanism: Related to H1 antihistamine blockade and 5-HT2C receptor effects [30]

- Monitor weight regularly, especially in the first months of treatment

- Consider alternative antidepressants in:

- Patients with obesity or metabolic syndrome

- Cases where weight gain could worsen comorbid conditions

- Among antidepressants with the greatest impact on weight [27]

- Increased appetite (17% incidence) [1,31]

- May be used therapeutically in elderly or cancer patients needing appetite stimulation [32,33]

- Occurs early in treatment [34]

- Dry mouth (25% incidence) [1]

- Constipation (13% incidence) [1]

- Dizziness (7% incidence) [1]

- Dyslipidemia

- Increased cholesterol (15% incidence) [1]

- Elevated triglycerides (6% incidence)

- Studies support the hypothesis that mirtazapine has direct pharmacological effects on lipid metabolism, independent of weight gain [35]

- Consider baseline and periodic lipid monitoring

- Hyponatremia (3-4% incidence) [36]

- Ranking of risk [37]:

- MAOIs > SNRIs > SSRIs > TCAs > Mirtazapine

- Often considered the antidepressant of choice for hyponatremia-prone patients [36]

- Ranking of risk [37]:

Severe side effects

- Hematologic abnormalities

- Agranulocytosis and severe neutropenia

- Rare but serious adverse effect

- Onset ranged from 1 day to 8 months after initiation, with the majority of cases occurring within 1 month after starting mirtazapine [38]

- Mechanism poorly understood, proposed pathways involve immune-mediated neutrophil destruction and direct toxic effects on bone marrow precursor cells [38,39]

- Monitor for signs of infection (fever, sore throat, flu-like symptoms) [1]

- Discontinue if white blood cell count drops significantly [1]

- Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia [40,41]

- Non-dose-dependent

- Immunologic mechanism involves drug-dependent antibodies that bind to platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complexes [42]

- Agranulocytosis and severe neutropenia

- Serotonin syndrome

- Risk increases with other serotonergic drugs

- Has also been reported rarely in monotherapy at therapeutic doses [43]

- Some clinicians argue that mirtazapine’s receptor binding profile, which does not significantly increase synaptic serotonin levels, makes it mechanistically improbable for the drug to cause true serotonin toxicity, suggesting reported cases may represent misclassification of other adverse effects [44,45]

- Use caution when combining mirtazapine with serotonergic medications, especially during treatment initiation or dose adjustments [1]

- Activation of mania/hypomania

- Although rare, cases with mirtazapine have been reported [46,47]

- May present atypically with dysphoria and agitation [48]

- QT prolongation

- Risk increases with higher doses

- Doses up to 45 mg generally considered to have minimal clinical impact on QT interval [1,49]

- Use caution in patients with cardiovascular disease [1]

- Discontinuation syndrome

- SNRIs, paroxetine, and mirtazapine have the highest risk among antidepressants [50]

- Symptoms may include dizziness, nausea, anxiety, and sleep disturbances [1,51]

- Rare manifestations involve withdrawal-induced mania/hypomania and pruritus [52,53]

- Mechanism attributed to sudden removal of 5-HT2/5-HT3 receptor blockade, H1-receptor rebound may cause dizziness [54]

- Gradual tapering recommended to minimize risk [1]

Other side effects

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Infrequently reported adverse effect [1,55]

- Mechanism: α1-adrenergic and H1 receptor antagonism [6]

- Consider monitoring blood pressure in high-risk patients

- Drug-induced movement disorders

- Akathisia

- More common at higher doses (30 mg/day) [ [56]; [57,58]

- Lower doses have been used to treat antipsychotic-induced akathisia , potentially due to 5-HT2A receptor blockade [59]

- Mechanism likely related to α2-adrenoreceptor blockade [57]

- Onset varies from immediate (single dose) to delayed (up to 20 years of treatment) [56]

- Dystonia and dyskinesia

- More common at lower doses (15 mg/day) [58]

- Related to 5-HT2 receptor inhibition and noradrenergic-dopaminergic imbalance [60,61]

- Restless leg syndrome (RLS)

- Associated with serotonergic modulation [62]

- Akathisia

Use in special populations

Pregnancy

- First-trimester safety

- Congenital malformations risk

- No increased risk of congenital malformations according to multiple studies, including a nationwide medical birth register [63,64]

- Congenital malformations risk

- Pregnancy complications

- Possible increased preterm birth risk (13% vs 2% in controls) [65]

- No increased risk of:

- Stillbirth or neonatal death [64]

- Low birth weight [65]

- Preeclampsia [66]

- Neonatal adaptation

- Poor neonatal adaptation in about one-third of exposed infants [67]

- Generally mild and self-limiting effects [68,69]

Breastfeeding

- Mirtazapine is present in breast milk [1,70]

- Generally considered acceptable during breastfeeding due to minimal infant exposure [71]

- Drug levels in breastmilk are low [1]

- Infant serum levels typically <1% of maternal levels [70]

- No reported serious adverse effects in breastfed infants [69]

- Breastfed infants should be monitored for [71]

- Sedation

- Poor feeding patterns.

- Weight gain adequacy.

- Development

- When initiating antidepressant therapy in treatment-naive patients:

- SSRIs are typically first-line options [72]

- Mirtazapine may be considered if maternal history suggests better tolerability [69]

Hepatic impairment

- Mirtazapine should be used with caution in patients with impaired hepatic function [1]

- Mild to moderate cirrhosis (Child-Pugh Class A/B)

- Starting dose: Administer 50% of the normal indication-specific starting dose [73,74]

- Maximum dose: 30 mg/day

- Monitor closely for adverse effects

- Child-Pugh Class C [75]

- Consider alternative agents

- If use is required:

- Start at 50% of usual dose

- Maximum: 30 mg/day

- Close monitoring essential

Renal impairment

- ClCr ≥30 mL/minute [1]

- No dosage adjustment necessary

- ClCr <30 mL/minute and hemodialysis/peritoneal dialysis [1,76]

- Initial: 7.5 to 15 mg once daily

- Titrate slowly with close monitoring

- Clearance reduced by ~50% in severe impairment

Elderly

- Consider lower starting doses (7.5 mg once daily) [1]

- Clearance reduced (40% lower in elderly males and 10% lower in elderly females) [1]

- Elderly patients may be at increased risk of hyponatremia with mirtazapine, though the incidence is lower compared to other antidepressants [1,37]

Patients with Phenylketonuria

- Mirtazapine orally disintegrating tablets (Remeron SolTab) contains phenylalanine (from aspartame) [1]

Brand names

- US: Remeron, Remeron SolTab

- Canada: APO‐Mirtazapine, Auro‐Mirtazapine, Auro‐Mirtazapine OD, MYLAN‐Mirtazapine, NRA‐Mirtazapine, PMS‐Mirtazapine, PRO‐Mirtazapine, Remeron, Remeron RD, SANDOZ Mirtazapine, TEVA‐Mirtazapine

- Other countries/regions: Actizipine, ADCO Mirteron, Alpreak, Amirel, Amiron, Aprimertaz, Arintapin, Auromirta oro, Aurozapine, Avanza, Bilanz, Calixta, Ciblex, Combar, Comenter, Contrelmin, Conalpin, Depreram, Dinertone, Deprezapina, Divaril, Elaxine, Esprital, Exania, Epilfarmo, Farmapina, Itazpam, Jeta, Jewell, Kang duo ning, M zap, Matiz, Maz, Mazipine, Melinton, Mira, Miramind, Mirap, Miradep, Miraz, Mirazagen, Mirazep, Mirdep, Mirfast, Miro, Miron, Mirnite, Mirpine, Mirsol, Milta, Milta od, Mipine, Mirt, Mirtabene, Mirtachem, Mirtalab, Mirtalich, Mirtagen, Mirtagamma, Mirtamerck, Mirtamylan, Mirtamor, Mirtan, Mirtapax, Mirtaril, Mirtatsapiini ennapharma, Mirtatsapiini Teva, Mirtastad, Mirtastadin, Mirtawin, Mirtax, Mirtel, Mitaprex, Mitapin, Mitocent, Mitpin, Mitraford, Mitrazac, Mzapine, Mirzaten, Mirzaten Q Tab, Mirzagen, Mirastad, Multapine, Mirzentac, Mirzentac od, Nasdep, Noxibel, Ociples, Ociplos, Odonazin, Orzap, Pai di sheng, Psidep, Rapine, Ramizipine, Rapizapine, Rejoy, Reflex, Remedrint, Remeron, Remergil, Remirta, Remirta oro, Remeron soltab, Rezam, Redepra, Remixil, Ramure, Saxib, Segmir, Shakes, Sypine, Sinmaron, Smilon, Tazepin, Tazamel, Tasomin, Terladep, Tazip, Tizapine, Trimazimyl, U Mirtaron, U-Zepine, Valdren, Velorin OD, Vastat, Vastat flas, Zapsy, Zania, Zatimar, Zemer, Zapimert, Zapex, Zestat, Zimvaken, Zispin, Zismirt, Zispin soltab, Zulin, Zuleptan, Zamir 15, Zamir 30, Zymron, Zipdep, Zapmir

References

- Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (2021). RemeronFDA.pdf. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/020415s038,021208s028lbl.pdf

- Al-Majed, A., Bakheit, A. H., Alharbi, R. M., & Abdel Aziz, H. A. (2018). Chapter Two – Mirtazapine. In H. G. Brittain (Ed.), Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology (Vol. 43, pp. 209–254). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.podrm.2018.01.002

- Schwasinger-Schmidt, T. E., & Macaluso, M. (2019). Other Antidepressants. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 250, 325–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2018_167

- de Boer, T. (1996). The pharmacologic profile of mirtazapine. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 57 Suppl 4, 19–25.

- Hassanein, E. H. M., Althagafy, H. S., Baraka, M. A., Abd-alhameed, E. K., & Ibrahim, I. M. (2024). Pharmacological update of mirtazapine: A narrative literature review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 397(5), 2603–2619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-023-02818-6

- Anttila, S. A. K., & Leinonen, E. V. J. (2006). A Review of the Pharmacological and Clinical Profile of Mirtazapine. CNS Drug Reviews, 7(3), 249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00198.x

- Iwamoto, K., Kawano, N., Sasada, K., Kohmura, K., Yamamoto, M., Ebe, K., Noda, Y., & Ozaki, N. (2013). Effects of low-dose mirtazapine on driving performance in healthy volunteers. Human Psychopharmacology, 28(5), 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2327

- Karsten, J., Hagenauw, L. A., Kamphuis, J., & Lancel, M. (2017). Low doses of mirtazapine or quetiapine for transient insomnia: A randomised, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 31(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116681399

- Radhakishun, F. S., van den Bos, J., van der Heijden, B. C., Roes, K. C., & O’Hanlon, J. F. (2000). Mirtazapine effects on alertness and sleep in patients as recorded by interactive telecommunication during treatment with different dosing regimens. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20(5), 531–537. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004714-200010000-00006

- Timmer, C. J., Sitsen, J. M., & Delbressine, L. P. (2000). Clinical pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 38(6), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200038060-00001

- Trintellix FDA.pdf. (n.d.).

- Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Adams, C., Bahji, A., Beaulieu, S., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Blumberger, D. M., Brietzke, E., Chakrabarty, T., Do, A., Frey, B. N., Giacobbe, P., Gratzer, D., Grigoriadis, S., Habert, J., Ishrat Husain, M., Ismail, Z., McGirr, A., … Milev, R. V. (2024). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023 : Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can. J. Psychiatry, 69(9), 641–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437241245384

- Bauer, M., Pfennig, A., Severus, E., Whybrow, P. C., Angst, J., Möller, H.-J., & Šon behalf of the Task Force on Unipolar Depressive Disorders. (2013). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Unipolar Depressive Disorders, Part 1: Update 2013 on the acute and continuation treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 14(5), 334–385. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2013.804195

- Bandelow, B., Allgulander, C., Baldwin, D. S., Costa, D. L. da C., Denys, D., Dilbaz, N., Domschke, K., Eriksson, E., Fineberg, N. A., Hättenschwiler, J., Hollander, E., Kaiya, H., Karavaeva, T., Kasper, S., Katzman, M., Kim, Y.-K., Inoue, T., Lim, L., Masdrakis, V., … Zohar, J. (2023). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders – Version 3. Part I: Anxiety disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry, 24(2), 79–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2022.2086295

- The Management of Major Depressive Disorder Work Group. (2022). Management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (2022). Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/

- Ribeiro, L., Busnello, J. V., Kauer-Sant’Anna, M., Madruga, M., Quevedo, J., Busnello, E. A., & Kapczinski, F. (2001). Mirtazapine versus fluoxetine in the treatment of panic disorder. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research = Revista Brasileira De Pesquisas Medicas E Biologicas, 34(10), 1303–1307. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-879×2001001000010

- Sarchiapone, M., Amore, M., De Risio, S., Carli, V., Faia, V., Poterzio, F., Balista, C., Camardese, G., & Ferrari, G. (2003). Mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder: An open-label trial. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(1), 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200301000-00006

- Montañés-Rada, F., De Lucas-Taracena, M. T., & Sánchez-Romero, S. (2005). Mirtazapine versus paroxetine in panic disorder: An open study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 9(2), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651500510018248

- Boshuisen, M. L., Slaap, B. R., Vester-Blokland, E. D., & den Boer, J. A. (2001). The effect of mirtazapine in panic disorder: An open label pilot study with a single-blind placebo run-in period. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(6), 363–368. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200111000-00008

- Serretti, A., & Chiesa, A. (2009). Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f

- Montejo, A. L., Prieto, N., de Alarcón, R., Casado-Espada, N., de la Iglesia, J., & Montejo, L. (2019). Management Strategies for Antidepressant-Related Sexual Dysfunction: A Clinical Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(10), 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101640

- Gelenberg, A. J., McGahuey, C., Laukes, C., Okayli, G., Moreno, F., Zentner, L., & Delgado, P. (2000). Mirtazapine substitution in SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(5), 356–360. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v61n0506

- Ozmenler, N. K., Karlidere, T., Bozkurt, A., Yetkin, S., Doruk, A., Sutcigil, L., Cansever, A., Uzun, O., Ozgen, F., & Ozsahin, A. (2008). Mirtazapine augmentation in depressed patients with sexual dysfunction due to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Human Psychopharmacology, 23(4), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.929

- Atmaca, M., Korkmaz, S., Topuz, M., & Mermi, O. (2011). Mirtazapine augmentation for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction: A retropective investigation. Psychiatry Investigation, 8(1), 55–57. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2011.8.1.55

- Nutt, D. (1997). Mirtazapine: Pharmacology in relation to adverse effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 391, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb05956.x

- Papazisis, G., Siafis, S., & Tzachanis, D. (2018). Tachyphylaxis to the Sedative Action of Mirtazapine. The American Journal of Case Reports, 19, 410–412. https://doi.org/10.12659/ajcr.908412

- Serretti, A., & Mandelli, L. (2010). Antidepressants and body weight: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(10), 1259–1272. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09r05346blu

- Blumenthal, S. R., Castro, V. M., Clements, C. C., Rosenfield, H. R., Murphy, S. N., Fava, M., Weilburg, J. B., Erb, J. L., Churchill, S. E., Kohane, I. S., Smoller, J. W., & Perlis, R. H. (2014). An Electronic Health Records Study of Long-term Weight Gain Following Antidepressant Use. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(8), 889–896. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.414

- Gafoor, R., Booth, H. P., & Gulliford, M. C. (2018). Antidepressant utilisation and incidence of weight gain during 10 years’ follow-up: Population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 361, k1951. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1951

- Salvi, V., Mencacci, C., & Barone-Adesi, F. (2016). H1-histamine receptor affinity predicts weight gain with antidepressants. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(10), 1673–1677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.08.012

- Hennings, J. M., Heel, S., Lechner, K., Uhr, M., Dose, T., Schaaf, L., Holsboer, F., Lucae, S., Fulda, S., & Kloiber, S. (2019). Effect of mirtazapine on metabolism and energy substrate partitioning in healthy men. JCI Insight, 4(1), e123786. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.123786

- Arrieta, O., Cárdenas-Fernández, D., Rodriguez-Mayoral, O., Gutierrez-Torres, S., Castañares, D., Flores-Estrada, D., Reyes, E., López, D., Barragán, P., Soberanis Pina, P., Cardona, A. F., & Turcott, J. G. (2024). Mirtazapine as Appetite Stimulant in Patients With Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer and Anorexia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology, 10(3), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.5232

- Avena-Woods, C., & Hilas, O. (2012). Antidepressant use in underweight older adults. The Consultant Pharmacist: The Journal of the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists, 27(12), 868–870. https://doi.org/10.4140/TCP.n.2012.868

- Nutt, D. J. (2002). Tolerability and safety aspects of mirtazapine. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 17(S1), S37–S41. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.388

- Lechner, K., Heel, S., Uhr, M., Dose, T., Holsboer, F., Lucae, S., Schaaf, L., Fulda, S., Kloiber, S., & Hennings, J. M. (2023). Weight-gain independent effect of mirtazapine on fasting plasma lipids in healthy men. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 396(9), 1999–2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-023-02448-y

- Moscona-Nissan, A., López-Hernández, J. C., & González-Morales, A. P. (n.d.). Mirtazapine Risk of Hyponatremia and Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion in Adult and Elderly Patients: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 13(12), e20823. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20823

- Gheysens, T., Van Den Eede, F., & De Picker, L. (2024). The risk of antidepressant-induced hyponatremia: A meta-analysis of antidepressant classes and compounds. European Psychiatry, 67(1), e20. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2024.11

- Kharel, H., Anjum, Z., Kharel, Z., Sugastti, E. F. A., Verghese, B. G., & Kouides, P. A. (2023). Mirtazapine induced neutropenia: A case report and systematic review. Revista Hematología, 27(2, 2), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.48057/hematologa.v27i2.535

- Johnston, A., & Uetrecht, J. (2015). Current understanding of the mechanisms of idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 11(2), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425255.2015.985649

- Arnold, D. M., Kukaswadia, S., Nazi, I., Esmail, A., Dewar, L., Smith, J. W., Warkentin, T. E., & Kelton, J. G. (2013). A systematic evaluation of laboratory testing for drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH, 11(1), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12052

- Stuhec, M., Alisky, J., & Malesic, I. (2014). Mirtazapine associated with drug-related thrombocytopenia: A case report. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 34(5), 662–664. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000201

- Liu, X., & Sahud, M. A. (2003). Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex is the target in mirtazapine-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases, 30(3), 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1079-9796(03)00037-8

- Ubogu, E. E., & Katirji, B. (2003). Mirtazapine-induced serotonin syndrome. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 26(2), 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002826-200303000-00002

- Berling, I., & Isbister, G. K. (2014). Mirtazapine overdose is unlikely to cause major toxicity. Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.), 52(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2013.859264

- Gillman, P. K. (2003). Mirtazapine: Unable to Induce Serotonin Toxicity? Clinical Neuropharmacology, 26(6), 288. https://journals.lww.com/clinicalneuropharm/citation/2003/11000/mirtazapine__unable_to_induce_serotonin_toxicity_.3.aspx

- Basavraj, V., Nanjundappa, G. B., & Chandra, P. S. (2011). Mirtazapine induced mania in a woman with major depression in the absence of features of bipolarity. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(10), 901. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2011.589369

- Soutullo, C. A., McElroy, S. L., & Keck, P. E. (1998). Hypomania associated with mirtazapine augmentation of sertraline. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(6), 320. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v59n0608e

- Bhanji, N. H., Margolese, H. C., Saint-Laurent, M., & Chouinard, G. (2002). Dysphoric mania induced by high-dose mirtazapine: A case for ’norepinephrine syndrome’? International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17(6), 319–322. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200211000-00009

- Allen, N. D., Leung, J. G., & Palmer, B. A. (2020). Mirtazapine’s effect on the QT interval in medically hospitalized patients. The Mental Health Clinician, 10(1), 30–33. https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.2020.01.030

- Horowitz, M. A., Framer, A., Hengartner, M. P., Sørensen, A., & Taylor, D. (2023). Estimating Risk of Antidepressant Withdrawal from a Review of Published Data. CNS Drugs, 37(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y

- Berigan, T. R. (2001). Mirtazapine-Associated Withdrawal Symptoms: A Case Report. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 3(3), 143. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v03n0307a

- Pombo, R., Johnson, E., Gamboa, A., & Omalu, B. (2017). Autopsy-proven Mirtazapine Withdrawal-induced Mania/Hypomania Associated with Sudden Death. Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics, 8(4), 185–187. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpp.JPP_162_16

- Spitznogle, B., & Gerfin, F. (2019). Pruritus associated with abrupt mirtazapine discontinuation: Single case report. The Mental Health Clinician, 9(6), 401–403. https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.2019.11.401

- Cosci, F. (2017). Withdrawal symptoms after discontinuation of a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant: A case report and review of the literature. Personalized Medicine in Psychiatry, 1–2, 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmip.2016.11.001

- Khawaja, I. S., & Feinstein, R. E. (2003). Cardiovascular effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other novel antidepressants. Heart Disease (Hagerstown, Md.), 5(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hdx.0000061695.97215.64

- Markoula, S., Konitsiotis, S., Chatzistefanidis, D., Lagos, G., & Kyritsis, A. P. (2010). Akathisia induced by mirtazapine after 20 years of continuous treatment. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 33(1), 50–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181bf213b

- Raveendranathan, D., & Swaminath, G. R. (2015). Mirtazapine Induced Akathisia: Understanding a Complex Mechanism. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(4), 474–475. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.168615

- Yoon, W. T. (2018). Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders Induced by Mirtazapine: Unusual Case Report and Clinical Analysis of Reported Cases. Journal of Psychiatry, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.4172/2378-5756.1000437

- Praharaj, S. K., Kongasseri, S., Behere, R. V., & Sharma, P. S. V. N. (2015). Mirtazapine for antipsychotic-induced acute akathisia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 5(5), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125315601343

- Konitsiotis, S., Pappa, S., Mantas, C., & Mavreas, V. (2005). Acute reversible dyskinesia induced by mirtazapine. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 20(6), 771. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.20432

- Balaz, M., & Rektor, I. (2010). Gradual onset of dyskinesia induced by mirtazapine. Neurology India, 58(4), 672–673. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.68693

- Makiguchi, A., Nishida, M., Shioda, K., Suda, S., Nisijima, K., & Kato, S. (2015). Mirtazapine-induced restless legs syndrome treated with pramipexole. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 27(1), e76. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13120357

- Winterfeld, U., Klinger, G., Panchaud, A., Stephens, S., Arnon, J., Malm, H., te Winkel, B., Clementi, M., Pistelli, A., Manakova, E., Eleftheriou, G., Merlob, P., Kaplan, Y. C., Buclin, T., & Rothuizen, L. E. (2015). Pregnancy Outcome Following Maternal Exposure to Mirtazapine A Multicenter, Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 35(3), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000309

- Ostenfeld, A., Petersen, T. S., Pedersen, L. H., Westergaard, H. B., Løkkegaard, E. C. L., & Andersen, J. T. (2022). Mirtazapine exposure in pregnancy and fetal safety: A nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 145(6), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13431

- Djulus, J., Koren, G., Einarson, T. R., Wilton, L., Shakir, S., Diav-Citrin, O., Kennedy, D., Voyer Lavigne, S., De Santis, M., & Einarson, A. (2006). Exposure to mirtazapine during pregnancy: A prospective, comparative study of birth outcomes. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(8), 1280–1284. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v67n0817

- Palmsten, K., Huybrechts, K. F., Michels, K. B., Williams, P. L., Mogun, H., Setoguchi, S., & Hernández-Díaz, S. (2013). Antidepressant use and risk for preeclampsia. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 24(5), 682–691.

- Kieviet, N., Hoppenbrouwers, C., Dolman, K. M., Berkhof, J., Wennink, H., & Honig, A. (2015). Risk factors for poor neonatal adaptation after exposure to antidepressants in utero. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992), 104(4), 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12921

- Grigoriadis, S., VonderPorten, E. H., Mamisashvili, L., Eady, A., Tomlinson, G., Dennis, C.-L., Koren, G., Steiner, M., Mousmanis, P., Cheung, A., & Ross, L. E. (2013). The effect of prenatal antidepressant exposure on neonatal adaptation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(4), e309–320. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r07967

- Smit, M., Dolman, K. M., & Honig, A. (2016). Mirtazapine in pregnancy and lactation – A systematic review. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(1), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.06.014

- Aichhorn, W., Whitworth, A. B., Weiss, U., & Stuppaeck, C. (2004). Mirtazapine and breast-feeding. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(12), 2325. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2325

- Kristensen, J. H., Ilett, K. F., Rampono, J., Kohan, R., & Hackett, L. P. (2007). Transfer of the antidepressant mirtazapine into breast milk. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 63(3), 322–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02773.x

- Sriraman, N. K., Melvin, K., Meltzer-Brody, S., & the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. (2015). ABM Clinical Protocol #18: Use of Antidepressants in Breastfeeding Mothers. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(6), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.29002

- Mauri, M. C., Fiorentini, A., Paletta, S., & Altamura, A. C. (2014). Pharmacokinetics of antidepressants in patients with hepatic impairment. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 53(12), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-014-0187-5

- Mullish, B. H., Kabir, M. S., Thursz, M. R., & Dhar, A. (2014). Review article: Depression and the use of antidepressants in patients with chronic liver disease or liver transplantation. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12925

- Rogal, S. S., Hansen, L., Patel, A., Ufere, N. N., Verma, M., Woodrell, C. D., & Kanwal, F. (2022). AASLD Practice Guidance: Palliative care and symptom-based management in decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 76(3), 819–853. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32378

- Nagler, E. V., Webster, A. C., Vanholder, R., & Zoccali, C. (2012). Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety with recommendations by European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation: Official Publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association – European Renal Association, 27(10), 3736–3745. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfs295