In a nutshell

When pharmacotherapy is indicated for unipolar depression, SSRIs are the default first-line choice, with sertraline 50 mg or escitalopram 10 mg as standard starting points. However, specific patient characteristics and preferences may favor alternative agents.

- Key principles for initial selection:

- Match intensity to severity:

- For mild MDD, prioritize psychotherapy.

- For moderate MDD, offer a choice between psychotherapy or an antidepressant.

- For severe MDD, recommend combination therapy (psychotherapy + antidepressant) from the start.

- Match intensity to severity:

- Practical starting points & monitoring:

- Default first-line agent:

- When there is no compelling reason to choose otherwise, an SSRI is the standard starting point due to a favorable balance of efficacy and tolerability.

- Default SSRIs: Sertraline 50 mg or escitalopram 10 mg (start at half-dose in anxiety-prone patients)

- Tailor to the patient profile:

- For prominent fatigue or to avoid sexual side effects, consider bupropion.

- For significant insomnia and/or weight loss, consider mirtazapine.

- If there are weight-gain concerns, prefer bupropion; avoid mirtazapine/paroxetine.

- For comorbid neuropathic pain, consider an SNRI like duloxetine.

- Older adults:

- Follow the “start low, go slow” principle.

- Prefer agents like sertraline or escitalopram and monitor closely for hyponatremia, falls, and drug-drug interactions.

- Initial Follow-Up:

- Schedule the first follow-up within 1-2 weeks to assess tolerability, address side effects, and ensure adherence.

- Default first-line agent:

Introduction

A Practical Framework for the First Prescription

- Selecting the first antidepressant for a patient with MDD is one of the most common yet nuanced decisions in clinical practice.

- This guide’s goal is to provide clinically useful “nuggets” to aid the prescriber in making that critical first choice.

- We have distilled the convergent recommendations from the latest major clinical guidelines (CANMAT, RANZCP, NICE, ACP, VA/DoD) [1–5] and other authoritative resources to create a practical, actionable framework for initial pharmacotherapy selection.

- This guide focuses on initial pharmacotherapy

- Strategies for non-response (switch/augment), continuation/maintenance, and special diagnoses (psychotic depression, perinatal, etc.) follow separate algorithms in the source guidelines.

- The contemporary focus is now on a strategic matching of treatment to the patient [1,4], based on:

- Depression severity: Guiding the choice of treatment modality (e.g., psychotherapy vs. medication vs. combination)

- Patient characteristics: Personalizing medication selection based on symptom profile, comorbidities, and tolerability concerns

- Shared decision-making: Collaboratively aligning the evidence with the patient’s unique values and preferences

Initial Assessment and Principles of Care

- Goals [1,6,7]

- Confirm MDD diagnosis

- Rule out conditions that change first-line choices

- Set up a quick, measurable plan for the first 4–8 weeks

Confirming the Diagnosis and Safety

- Screen for bipolar spectrum (brief mania screen/MDQ + history of antidepressant-induced activation)

- Before initiating an antidepressant, screen for a personal or family history of mania or hypomania to rule out bipolar disorder.

- Red flags for potential bipolar spectrum disorder include a history of antidepressant-induced mood elevation, recurrent depressive episodes, and early onset (<25 years).

- Targeted medical screen:

- A targeted medical workup is often appropriate.

- Baseline labs typically include CBC and TSH; test further based on clinical suspicion (e.g., B12, LFTs, electrolytes) [1]

Core Principles of Management

- Shared Decision-Making (SDM):

- The clinician and patient work as partners

- This process involves a transparent discussion of all evidence-based treatment options (including no treatment), their respective benefits and harms

- Align the final choice with the patient’s values, preferences, and life circumstances

- Measurement-Based Care (MBC):

- MBC is an evidence-based practice comprising three essential components [1,5]

- Regular use of validated outcome scales during patient encounters

- Review of scale scores with patients to facilitate shared understanding.

- Use of scores alongside clinical assessment to support collaborative decision-making

- Meta-analyses show patients receiving MBC are more likely to achieve remission and experience improved treatment adherence [8,9]

- MBC is an evidence-based practice comprising three essential components [1,5]

- Recommended Assessment Tools

- The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)[10,11] is the most widely recommended tool for monitoring depression symptoms due to being:

- Short and self-administered

- Extensively validated across diverse populations

- Aligned with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria

- Sensitive to change over time

- PHQ-9 Scoring and Interpretation [5,12]

- Mild depression: 5-9

- Moderate depression: 10-14

- Moderately severe: 15-19

- Severe depression: ≥20

- Clinically meaningful change: ≥5 points

- Alternative validated scales include [1]

- Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR)

- Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS)

- Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

- Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

- The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)[10,11] is the most widely recommended tool for monitoring depression symptoms due to being:

- Use clear definitions for treatment milestones: – Goal: Remission (e.g., PHQ-9 < 5) – Response: ≥50% score reduction from baseline – Non-response: <25-30% score reduction after an adequate trial (typically 4-8 weeks at a therapeutic dose)

Treatment Intensity Selection by Severity Level

- The severity of the depressive episode is the primary factor guiding the modality of the initial treatment.

- Stratification helps frame the initial conversation with the patient, but the final choice should always be guided by shared decision-making, patient preference, and practical considerations like treatment availability.

Mild Depression (PHQ-9 ≈ 5–9, Limited Impairment)

- Initial approach:

- For patients with mild MDD, guidelines converge on recommending evidence-based psychotherapy as the preferred initial treatment when accessible [1,3,4,13]

- The rationale is to prioritize interventions with a favorable risk-benefit profile and lasting skills acquisition.

- Consider patient preference, cost, therapy availability, and previous treatment response

- Exercise programs, complementary/alternative treatments, or guided digital health interventions [1]

- Offer low-intensity options when preferred/feasible: supervised exercise, guided digital interventions/BA/CBT-based supports; use active surveillance with scheduled check-ins (CANMAT/NICE) [1,3]

- Alternative options:

- Antidepressant medication is a perfectly reasonable first-line choice if it aligns with the patient’s preference or if there are practical barriers to accessing timely psychotherapy

- “Active surveillance” (or “watchful waiting”) is an option for a first, mild episode with minimal functional impairment or for patients who do not want treatment or whose symptoms are improving [3]

- This is not passive waiting; it involves scheduling regular check-ins (e.g., in 2-4 weeks) to monitor symptom trajectory [3]

- Offer psychotherapy or antidepressants (not watchful waiting) if [14]

- Patients with mild MDD + prior depression history

- Significant functional impairment despite mild symptoms

- Symptoms >3 months

Moderate Depression (PHQ-9 ≈ 10–19, Clear Impairment)

- For moderate MDD, either evidence-based psychotherapy (like CBT) or a second-generation antidepressant is an appropriate and effective first-line treatment [13]

- The decision should be made collaboratively, and is driven by patient preference, prior response, cost, and availability of evidence-based psychotherapy [1,4]

- Patient preference: Some patients prefer therapy to avoid medication side effects. Antidepressants are often more available/convenient/less costly [4]

- Availability and cost: Access to qualified therapists can be a significant barrier

- Efficacy note: Head-to-head meta-analyses show CBT ≈ antidepressant for acute response/remission; psychotherapy may have more durable benefit after discontinuation (skills acquisition) [15–18]

- Antidepressants may be slightly more efficacious in reducing symptoms of depressed mood, guilt, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, and somatic symptoms during the acute treatment phase, but structured psychotherapy is more efficacious than antidepressants at 6- to 12-month follow-up [1]

- Adjuncts: Exercise and other supplemental interventions can be added to either path; they are adjuncts, not replacements, at this severity [1]

- Initial pharmacologic treatment options

- If pharmacotherapy is chosen, SSRIs (e.g., escitalopram or sertraline) are generally preferred due to their optimal balance of efficacy and tolerability [19]

- Combination (psychotherapy + medication)is a reasonable alternative, especially if partial response to monotherapy [1,4]

- Consider combination treatment if [20]

- Prior recurrent episodes

- Duration >6 months

- Active suicidal ideation

- Marked functional impairment

- Patient preference favors a faster/greater probability of benefit

- Consider combination treatment if [20]

Severe Depression (PHQ-9 ≥20 or Marked Impairment)

- Without psychotic features:

- Initial approach: combination of antidepressant + psychotherapy [1,3–5]

- While an SSRI is a reasonable first choice, some authors recommend trialing venlafaxine, mirtazapine, or a tricyclic antidepressant [19]

- These may be augmented if necessary with lithium or T3 (triiodothyronine).

- SNRIs (such as venlafaxine or duloxetine) may have a slight efficacy advantage in achieving remission in more severe or inpatient settings [21–23]

- Medication considerations: treatment may require higher doses or earlier augmentation

- With psychotic features:

- Treatment: Antidepressant + atypical antipsychotic

- Psychotherapy timing: Deferring structured therapy might be recommended until psychosis resolves [1]

- Life-threatening situations (severe suicidality, catatonia, physical deterioration):

- Consider ECT as first-line treatment [1]

- Hospitalization often required

Choosing an Initial Antidepressant

Why “Best Fit,” Not “Best Drug”

- The initial selection is rarely based on finding the “strongest” antidepressant but rather the “best fit” for the individual patient.

- Insights from large-scale network meta-analyses found that differences in efficacy are modest and often not clinically significant [24,25]

- The primary drivers of choice are [4] – Side effect profile and patient preferences for avoiding specific effects (e.g., weight gain, sexual dysfunction) – Patient comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions – Specific symptom clusters (e.g., insomnia, fatigue, comorbid pain) – Prior treatment history (personal or family) – Cost and availability

- Modern guidelines emphasize that between reasonable options, the choice should be personalized based on the patient’s symptoms (e.g. insomnia or hypersomnia, appetite changes), comorbidities, and preferences [4]

- In other words, the goal is finding the best fit for the patient’s profile, not necessarily a theoretical “best” drug

What’s “First-Line”?

- Second-generation antidepressants are the first-line pharmacologic choice for MDD due to their favorable balance of efficacy and tolerability. These include:

- SSRIs (e.g., sertraline, escitalopram, fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine)

- SNRIs (e.g., venlafaxine, duloxetine)

- Atypicals (bupropion, mirtazapine)

- Serotonin modulators (vortioxetine, vilazodone).

- Across guidelines SSRIs and SNRIs are core first-line classes; other SGAs antidepressants (e.g., bupropion, mirtazapine, vortioxetine) are also widely accepted and commonly used first-line depending on patient characteristics and priorities [1,4]

- Default to SSRIs (e.g., sertraline or escitalopram):

- In the absence of special considerations

- For outpatients without modifying comorbidities

- Meta-analyses suggest sertraline and escitalopram have slight advantages in efficacy/tolerability and few drug interactions [19,26]

- Clinical considerations:

- Start at half-dose in anxiety-prone patients (sertraline 25 mg, escitalopram 5 mg)

- Morning dosing typically preferred (except paroxetine – evening due to sedation)

- Allow 4-6 weeks before declaring treatment failure at therapeutic dose

- Bupropion is a reasonable alternative first-line—particularly if avoiding SSRI-related sexual adverse effects is a priority [19]

- For a patient who has failed SSRIs due to sexual side effects, or who has prominent fatigue or tobacco use, consider starting with bupropion

- Fluoxetine’s long half-life can be helpful if adherence is variable; paroxetine is less preferred due to weight gain and discontinuation symptoms.

- Older agents like Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) and Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) are reserved for second- or third-line use due to their significant side-effect burden and toxicity in overdose.

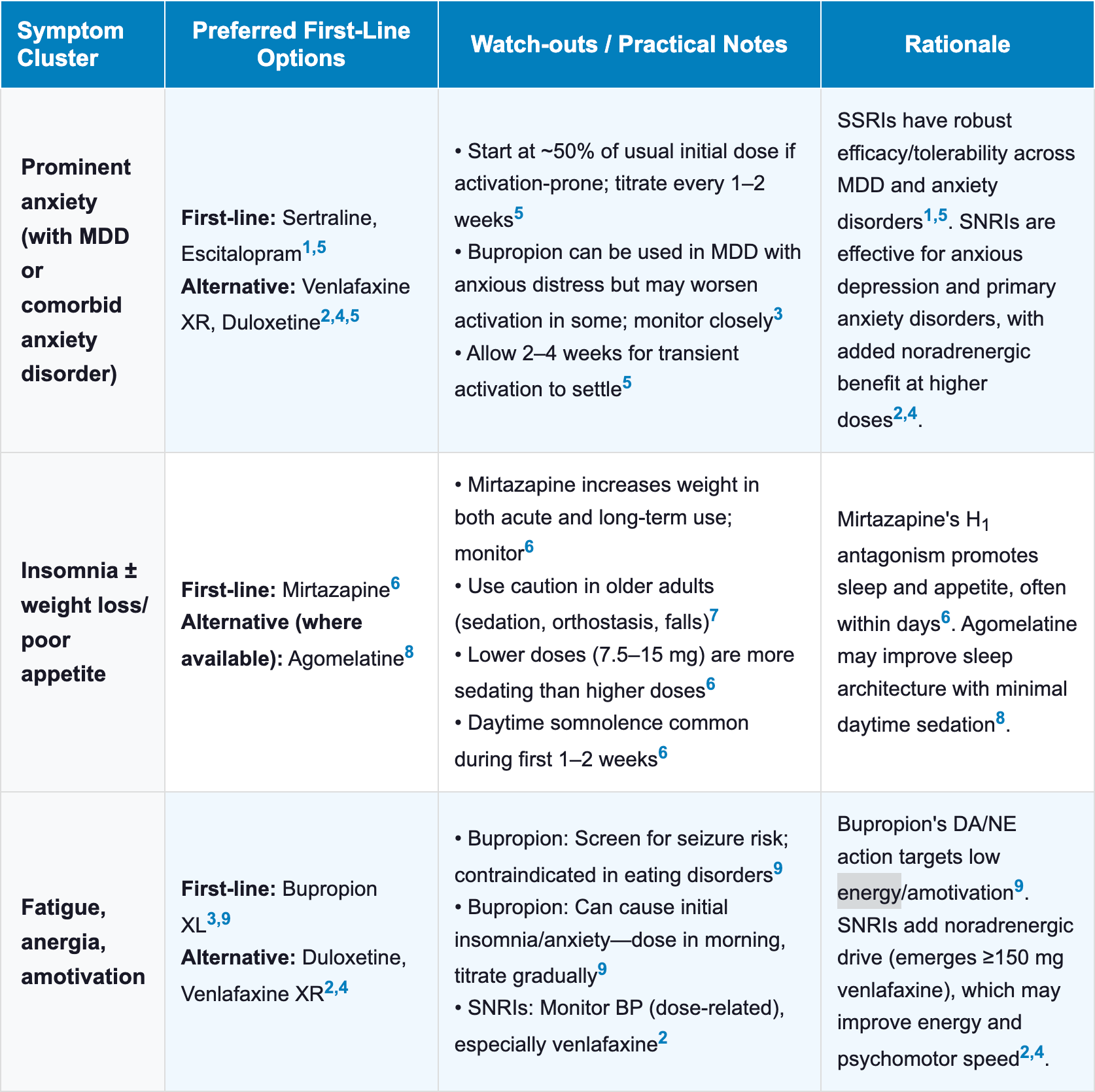

Antidepressant Selection by Symptom Cluster

- Matching the antidepressant to the patient’s predominant symptom cluster can help maximize the “best fit.”

- Below are common clinical scenarios and corresponding preferred agents

| Table 1 Antidepressant Selection by Symptom Cluster |

|---|

|

|

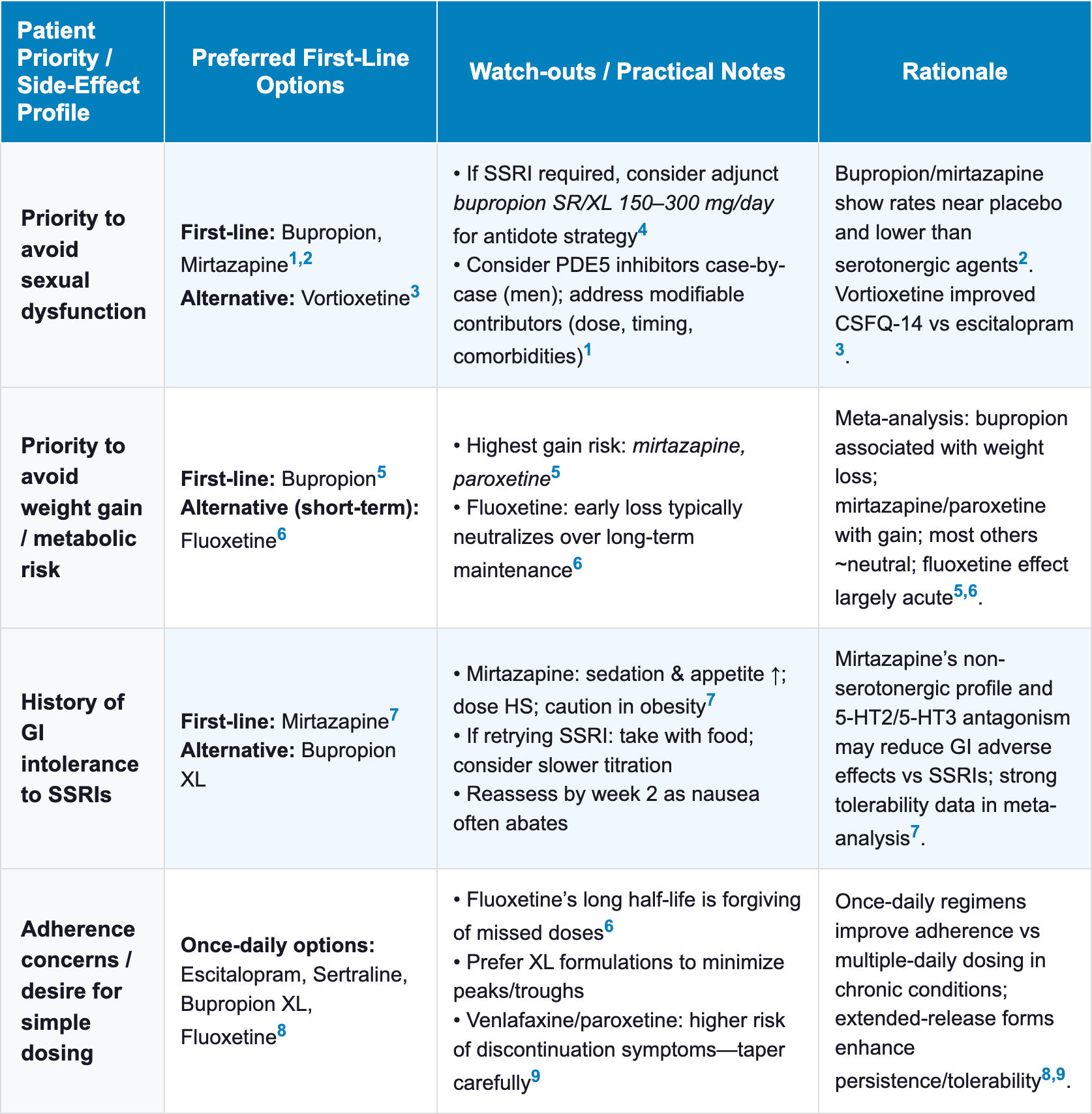

Antidepressant Selection by Patient Priorities and Side Effect Profile

| Table 2 Antidepressant Selection by Patient Priorities and Side Effect Profile |

|---|

|

|

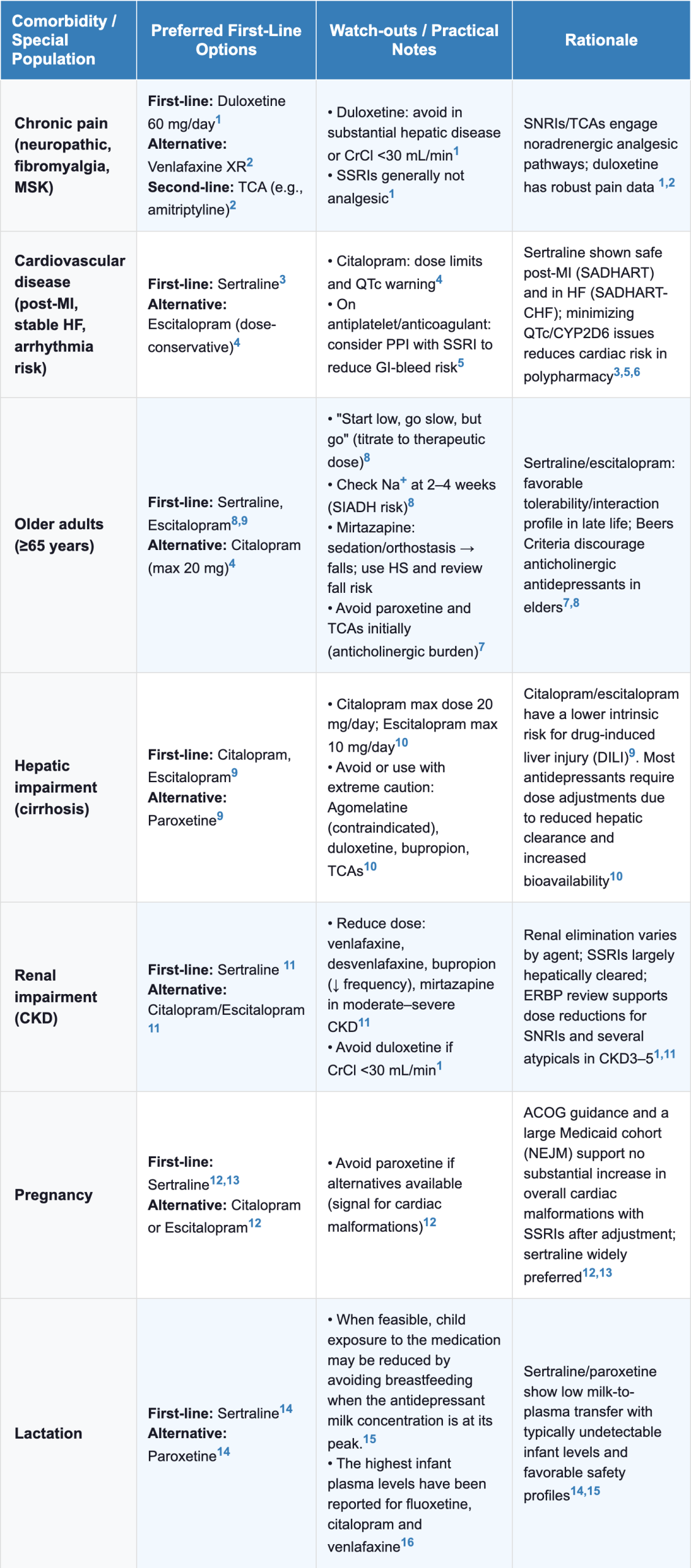

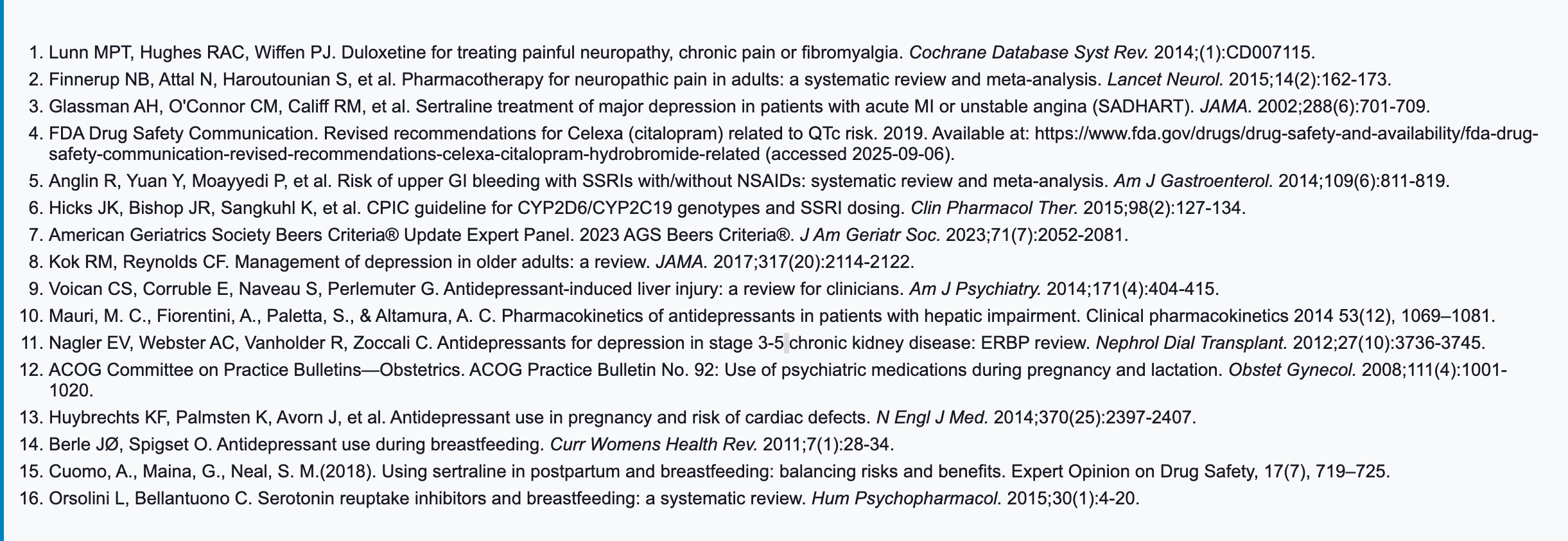

Antidepressant Selection in Comorbidities & Special Populations

| Table 3 Antidepressant Selection in Comorbidities & Special Populations |

|---|

|

|

Follow-Up and Monitoring After Initial Treatment

- Contemporary guidelines converge on measurement-based care (MBC) with routine, structured follow-up to optimize dose early, detect non-response, and manage safety.

- MBC uses brief validated scales (e.g., PHQ-9, QIDS-SR) at each contact to guide decisions and engage patients.

- This approach involves a collaborative review of progress with patients, and data-driven treatment adjustments [1,5]

Making Early Adjustments: Titrating the Dose

- Dose adjustment at 2-4 weeks

- For individuals who do not show an adequate response to the minimum therapeutic dose within two to four weeks, increasing the dose as tolerated toward the upper end of the usual dosing range is an alternative [27–29]

- Rapid titration:

- If the patient is tolerating the medication well, the dose can be increased relatively quickly.

- Gradual titration:

- If the patient is experiencing side effects or is reluctant to increase the dose, a more gradual titration is appropriate.

- In these cases, continuing the current dose is a reasonable alternative, as some patients will eventually respond without an increase.

- Rapid titration:

- Supporting evidence:

- Greater improvement in depression symptoms with higher doses of SSRIs reported in a large meta-analysis [30]

- This increased efficacy outweighed the higher rate of discontinuation due to side effects.

- However, the clinical benefit of higher doses was small and tended to plateau at the upper end of the therapeutic range.

- Greater improvement in depression symptoms with higher doses of SSRIs reported in a large meta-analysis [30]

- Countervailing evidence:

- Other meta-analyses have found that for patients who do not respond to an initial standard dose of an SSRI or SNRI, increasing the dose may not lead to significantly better outcomes than simply continuing the initial dose [31]

- For individuals who do not show an adequate response to the minimum therapeutic dose within two to four weeks, increasing the dose as tolerated toward the upper end of the usual dosing range is an alternative [27–29]

- Do not consider switching antidepressants until the patient has had an adequate trial (at least 4-6 weeks) at a therapeutic dose [32,33]

- For patients with a partial response, extending the trial to 6-12 weeks is reasonable before making a change [34,35]

References

- Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Adams, C., Bahji, A., Beaulieu, S., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Blumberger, D. M., Brietzke, E., Chakrabarty, T., Do, A., Frey, B. N., Giacobbe, P., Gratzer, D., Grigoriadis, S., Habert, J., Ishrat Husain, M., Ismail, Z., McGirr, A., … Milev, R. V. (2024). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023 : Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can. J. Psychiatry, 69(9), 641–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437241245384

- Malhi, G. S., Bell, E., Bassett, D., Boyce, P., Bryant, R., Hazell, P., Hopwood, M., Lyndon, B., Mulder, R., Porter, R., Singh, A. B., & Murray, G. (2021). The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55(1), 7–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420979353

- Depression in adults: Treatment and management. (2022). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583074/

- Qaseem, A., Owens, D. K., Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I., Tufte, J., Cross, J. T., Wilt, T. J., & Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. (2023). Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Treatments of Adults in the Acute Phase of Major Depressive Disorder: A Living Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 176(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.7326/M22-2056

- VA/DoD. (2022). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline The Management of Major Depressive Disorder. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/VADODMDDCPGFinal508.pdf

- Simon, G. E., Johnson, E., Lawrence, J. M., Rossom, R. C., Ahmedani, B., Lynch, F. L., Beck, A., Waitzfelder, B., Ziebell, R., Penfold, R. B., & Shortreed, S. M. (2018). Predicting Suicide Attempts and Suicide Deaths Following Outpatient Visits Using Electronic Health Records. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(10), 951–960. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101167

- McDowell, A. K., Lineberry, T. W., & Bostwick, J. M. (2011). Practical suicide-risk management for the busy primary care physician. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 86(8), 792–800. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2011.0076

- Zhu, M., Hong, R. H., Yang, T., Yang, X., Wang, X., Liu, J., Murphy, J. K., Michalak, E. E., Wang, Z., Yatham, L. N., Chen, J., & Lam, R. W. (2021). The Efficacy of Measurement-Based Care for Depressive Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(5), 21r14034. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21r14034

- Knaup, C., Koesters, M., Schoefer, D., Becker, T., & Puschner, B. (2009). Effect of feedback of treatment outcome in specialist mental healthcare: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 195(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053967

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- PHQ-9 Depression Screening Tool. (n.d.). Retrieved September 13, 2025, from https://www.phq-9.com/

- Löwe, B., Unützer, J., Callahan, C. M., Perkins, A. J., & Kroenke, K. (2004). Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Medical Care, 42(12), 1194–1201. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006

- Depression – ACP – YYYY – Guideline copy. (n.d.).

- Major depressive disorder in adults: Approach to initial management – UpToDate. (n.d.). Retrieved August 20, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/major-depressive-disorder-in-adults-approach-to-initial-management?search=Major%20depressive%20disorder%20in%20adults%3A%20Approach%20to%20initial%20management&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Cuijpers, P., Reynolds, C. F., Donker, T., Li, J., Andersson, G., & Beekman, A. (2012). Personalized treatment of adult depression: Medication, psychotherapy, or both? A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 29(10), 855–864. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21985

- Gartlehner, G., Nussbaumer‐Streit, B., Gaynes, B. N., Forneris, C. A., Morgan, L. C., Greenblatt, A., Wipplinger, J., Lux, L. J., Noord, M. G. V., & Winkler, D. (n.d.). Second‐generation antidepressants for preventing seasonal affective disorder in adults – Gartlehner, G – 2019 | Cochrane Library. Retrieved January 17, 2025, from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011268.pub3/full

- Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, S. L., Andersson, G., Beekman, A. T., & Reynolds, C. F. (2013). The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 12(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20038

- Spielmans, G. I., Berman, M. I., & Usitalo, A. N. (2011). Psychotherapy versus second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of depression: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(3), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31820caefb

- Osser, D. N. (2021). Psychopharmacology algorithms: Clinical guidance from the Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Psychiatry Residency Program. Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Driessen, E., Fokkema, M., Dekker, J. J. M., Peen, J., Van, H. L., Maina, G., Rosso, G., Rigardetto, S., Cuniberti, F., Vitriol, V. G., Andreoli, A., Burnand, Y., López Rodríguez, J., Villamil Salcedo, V., Twisk, J. W. R., Wienicke, F. J., & Cuijpers, P. (2023). Which patients benefit from adding short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy to antidepressants in the treatment of depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Psychological Medicine, 53(13), 6090–6101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722003270

- Bradley, A. J., & Lenox-Smith, A. J. (2013). Does adding noradrenaline reuptake inhibition to selective serotonin reuptake inhibition improve efficacy in patients with depression? A systematic review of meta-analyses and large randomised pragmatic trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 27(8), 740–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881113494937

- Schmitt, A. B., Bauer, M., Volz, H.-P., Moeller, H.-J., Jiang, Q., Ninan, P. T., & Loeschmann, P.-A. (2009). Differential effects of venlafaxine in the treatment of major depressive disorder according to baseline severity. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 259(6), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-009-0003-7

- Machado, M., Iskedjian, M., Ruiz, I., & Einarson, T. R. (2006). Remission, dropouts, and adverse drug reaction rates in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of head-to-head trials. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 22(9), 1825–1837. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079906X132415

- Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Salanti, G., Chaimani, A., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., Leucht, S., Ruhe, H. G., Turner, E. H., Higgins, J. P. T., Egger, M., Takeshima, N., Hayasaka, Y., Imai, H., Shinohara, K., Tajika, A., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Geddes, J. R. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet, 391(10128), 1357–1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32802-7

- Wagner, G., Schultes, M.-T., Titscher, V., Teufer, B., Klerings, I., & Gartlehner, G. (2018). Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran, vilazodone and vortioxetine compared with other second-generation antidepressants for major depressive disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 228, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.056

- Giakoumatos, C. I., & Osser, D. (2019). The Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Program: An Update on Unipolar Nonpsychotic Depression. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000197

- Spijker, J., & Nolen, W. A. (2010). An algorithm for the pharmacological treatment of depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 121(3), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01492.x

- Ruhé, H. G., Huyser, J., Swinkels, J. A., & Schene, A. H. (2006). Dose escalation for insufficient response to standard-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 189, 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018325

- Shelton, R. C., Osuntokun, O., Heinloth, A. N., & Corya, S. A. (2010). Therapeutic options for treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs, 24(2), 131–161. https://doi.org/10.2165/11530280-000000000-00000

- Jakubovski, E., Varigonda, A. L., Freemantle, N., Taylor, M. J., & Bloch, M. H. (2016). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Dose-Response Relationship of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Major Depressive Disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(2), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030331

- Rink, L., Braun, C., Bschor, T., Henssler, J., Franklin, J., & Baethge, C. (2018). Dose Increase Versus Unchanged Continuation of Antidepressants After Initial Antidepressant Treatment Failure in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Double-Blind Trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(3), 17r11693. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17r11693

- Papakostas, G. I. (2009). Managing partial response or nonresponse: Switching, augmentation, and combination strategies for major depressive disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70 Suppl 6, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.8133su1c.03

- Rush, A. J. (2007). STAR*D: What have we learned? The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(2), 201–204. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.201

- Quitkin, F. M., Petkova, E., McGrath, P. J., Taylor, B., Beasley, C., Stewart, J., Amsterdam, J., Fava, M., Rosenbaum, J., Reimherr, F., Fawcett, J., Chen, Y., & Klein, D. (2003). When should a trial of fluoxetine for major depression be declared failed? The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(4), 734–740. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.734

- Posternak, M. A., Baer, L., Nierenberg, A. A., & Fava, M. (2011). Response rates to fluoxetine in subjects who initially show no improvement. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(7), 949–954. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06098