In a nutshell

Buspirone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist and a second-line option for generalized anxiety disorder, typically considered when SSRIs are ineffective or poorly tolerated. Compared with benzodiazepines, it is generally less sedating and is not associated with clinically meaningful physical dependence or a significant withdrawal syndrome. Because food increases exposure, patients should take buspirone consistently—either always with food or always without food—to reduce variability in drug levels

- When to consider buspirone:

- Generalized anxiety disorder after inadequate response or intolerance to SSRIs

- GAD when benzodiazepines are contraindicated or undesirable

- History of substance use disorder

- Elderly patients at risk of falls or cognitive impairment

- Need for long-term anxiolytic treatment without dependence risk

- SSRI augmentation for major depression (STAR* D evidence supports comparable efficacy to bupropion augmentation)

- SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (may improve desire/frequency when added to SSRI therapy; evidence is mixed)

- Patients who must avoid sedation or psychomotor impairment (e.g., driving, operating machinery)

- Benzodiazepine-naïve patients with GAD who want a non-benzodiazepine option and can wait for delayed onset

- Prefer alternatives when:

- Acute or “as-needed” anxiety relief is required (buspirone has no immediate anxiolytic effect)

- Patient has recent (<1 month) or significant benzodiazepine exposure (higher dropout rates and reduced efficacy observed)

- Primary panic disorder, OCD, or PTSD (limited evidence; not recommended by most guidelines as a primary treatment)

- Treatment of benzodiazepine, barbiturate, or alcohol withdrawal

- Concurrent use of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers

- Pregnancy or lactation (limited human data; other agents preferred)

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

- Buspirone is an azapirone anxiolytic that is not chemically or pharmacologically related to benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or other sedative/anxiolytic drugs [1,2]

- Often termed “anxioselective” because it alleviates anxiety without exhibiting anticonvulsant, sedative, hypnotic, or muscle relaxant properties [1]

- Originally developed as an antipsychotic but found ineffective for psychosis; anxiolytic properties were subsequently recognized [2]

- Primary mechanism: 5-HT1A receptor partial agonism

- High affinity for serotonin 5-HT1A receptors, where it acts as a partial agonist [1–3]

- Presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors (dorsal raphe): Agonist activity, causing initial inhibition of serotonergic neuron firing

- Postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors (hippocampus, cortex): Partial agonist activity

- The underlying mechanism of how 5-HT1A partial agonism translates into anxiolysis remains incompletely understood.

- Delayed clinical onset (2–4 weeks) suggests anxiolytic effects occur through adaptive changes in 5-HT1A receptor sensitivity rather than acute receptor activation [4]

- Clinical implications:

- Augmentation of SSRI antidepressant effects [5,6]

- Attenuation of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction [7,8]

- High affinity for serotonin 5-HT1A receptors, where it acts as a partial agonist [1–3]

- Dopaminergic effects

- Moderate affinity for brain D2 dopamine receptors [1,2,9]

- Acts as a weak antagonist at D2 autoreceptors, which may increase dopamine release in certain brain regions [10]

- Clinical experience in controlled trials has not identified significant neuroleptic-like activity at therapeutic doses [1]

- Moderate affinity for brain D2 dopamine receptors [1,2,9]

- Noradrenergic effects

- Buspirone dose-dependently increases locus coeruleus noradrenergic neuronal firing

- This effect has been proposed to be mediated by the major metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine (1-PP), which acts as an α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist [11,12]

- This noradrenergic activation may contribute to the stimulant-type side effects (nervousness, dizziness, excitement) that occur more commonly than sedation

- Buspirone dose-dependently increases locus coeruleus noradrenergic neuronal firing

- Absence of GABAergic activity

- Buspirone has no significant affinity for benzodiazepine receptors [1]

- Does not affect GABA binding in vitro or in vivo

- Clinical implications:

- No sedative, hypnotic, or muscle relaxant effects

- Not associated with clinically meaningful physical dependence; does not produce a benzodiazepine-like withdrawal syndrome.

- No cross-tolerance with benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or alcohol

- Not effective to treat benzodiazepine or alcohol withdrawal

- Patients previously treated with benzodiazepines may have diminished response to buspirone [1,13]

Pharmacokinetics and Drug Interactions

Metabolism

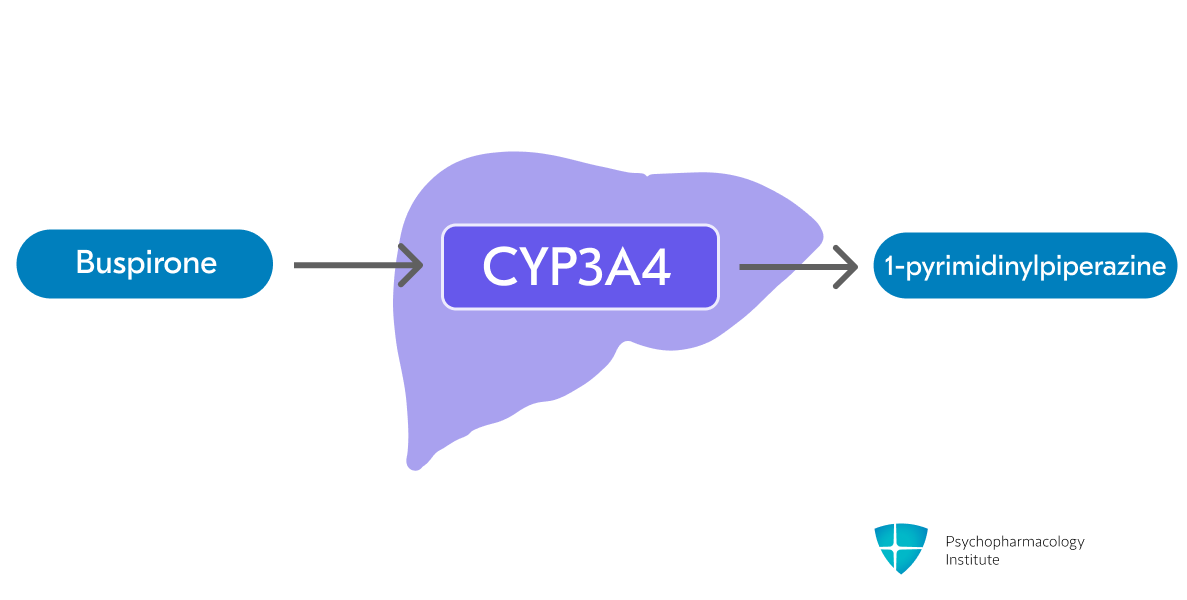

- Buspirone is metabolized primarily by hepatic oxidation via CYP3A4 [1,14]

- One of the major metabolites of buspirone is 1-pyrimidinylpiperazine (1-PP) [1,14]

- Acts as an α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist and may contribute to the psychostimulatory effects of buspirone [11,14]

- Acts as an α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist and may contribute to the psychostimulatory effects of buspirone [11,14]

Bioavailability Considerations

- Food effect [1,14]

- Food increases buspirone exposure (AUC and Cmax); it does not affect tmax and half-life

- Clinical recommendation: Take buspirone consistently — either always with food OR always without food — to avoid fluctuations in drug levels [1]

- Protein binding:

- Approximately 86% bound to plasma proteins [1,14]

- Aspirin increases free buspirone by ~23%; flurazepam decreases it by ~20%

- In vitro, buspirone does not displace highly protein-bound drugs (phenytoin, warfarin, propranolol) but may displace digoxin; clinical significance is uncertain [1]

Half-life

- Elimination half-life: 2–3 hours [1,14]

- Increased in hepatic and renal impairment [1,14,15]

Drug Interactions

Pharmacokinetic Interactions

- Buspirone levels markedly increased by

- CYP3A4 inhibitors

- Strong inhibitors: Use very low starting doses and titrate cautiously

- Itraconazole, nefazodone: Start at 2.5 mg once daily [1,16]

- Erythromycin: Start at 2.5 mg twice daily [16]

- Other potent CYP3A4 inhibitors (ketoconazole, ritonavir, clarithromycin, voriconazole): Use a low dose cautiously

- Grapefruit juice: Avoid large quantities [17]

- Moderate inhibitors: Use low dose with clinical assessment

- Diltiazem, verapamil: Start at reduced dose and titrate based on response

- Strong inhibitors: Use very low starting doses and titrate cautiously

- CYP3A4 inhibitors

- Buspirone levels decreased by

- Strong CYP3A4 inducers [1]

- Rifampin:

- May need to increase buspirone dose to maintain anxiolytic effect

- Other inducers: Carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, dexamethasone, St. John’s Wort

- Monitor for reduced efficacy and adjust buspirone dose as needed

- Rifampin:

- Strong CYP3A4 inducers [1]

- Effects on other drugs [1]

- Haloperidol: Buspirone may increase serum haloperidol concentrations, though the clinical significance is unclear

- Digoxin: Buspirone may displace digoxin from plasma proteins (in vitro)

- Warfarin: One case report of prolonged prothrombin time; monitor if used together

- No significant effect on steady-state pharmacokinetics of amitriptyline, diazepam, or benzodiazepines

Pharmacodynamic Interactions

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) [1]

- Avoid concomitant use due to risk of serotonin syndrome and/or elevated blood pressure

- Allow at least 14 days between discontinuing an MAOI and initiating buspirone, and vice versa

- Serotonergic drugs

- Concomitant use increases the risk of serotonin syndrome

- Examples: SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, triptans, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, St. John’s Wort

- CNS depressants [1]

- Buspirone may enhance CNS depressant effects of alcohol, though formal studies showed no significant alcohol-induced impairment increase

- Advise patients to avoid alcohol during treatment

- Benzodiazepines [1]

- Buspirone does not exhibit cross-tolerance with benzodiazepines

- No prolongation or intensification of sedative effects with triazolam or flurazepam

Drug/Laboratory Test Interactions

- Buspirone may interfere with the urinary metanephrine/catecholamine assay [1]

- Can cause false-positive results during routine assay testing for pheochromocytoma

- Discontinue buspirone at least 48 hours before urine collection for catecholamines

Dosage forms

- Immediate-release:

- Tablets

- 5 mg (scored), 7.5 mg (scored), 10 mg (scored), 15 mg (DIVIDOSE®, scored), 30 mg (DIVIDOSE®, scored)

- Generic, BuSpar (discontinued brand)

- Capsules

- 7.5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg

- Bucapsol

- Tablets

- Formulation considerations:

- Tablet scoring allows for flexible dosing:

- 5 mg and 10 mg tablets can be bisected (halved)

- 15 mg and 30 mg DIVIDOSE® tablets can be bisected or trisected

- Capsule administration:

- May be opened and contents sprinkled on 1–2 tablespoons of applesauce for patients with swallowing difficulties; swallow mixture immediately [18]

- Food and absorption:

- Food significantly increases bioavailability [1]

- Must be taken consistently with regard to food—either always with food or always without food—to maintain stable blood levels [1]

- Grapefruit juice should be avoided as it inhibits CYP3A4 and can significantly increase buspirone levels

- Tablet scoring allows for flexible dosing:

Indications

FDA-Approved Indications

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Buspirone is FDA-approved for “the management of anxiety disorders or the short-term relief of the symptoms of anxiety” [1]

- This broad labeling reflects the regulatory environment of the 1980s, when buspirone was approved under DSM-III criteria for anxiety disorders—a nosology that predated the current, more specific diagnostic categories

- Efficacy was demonstrated in controlled clinical trials of outpatients whose diagnosis corresponds to Generalized Anxiety Disorder [1,19]

- Many patients in registration trials had coexisting depressive symptoms, and buspirone relieved anxiety in the presence of these coexisting depressive symptoms [20]

- Clinical positioning

- Typically used as a second-line agent when patients do not respond to or cannot tolerate SSRIs [4,21,22]

- Effective for GAD, though effect sizes are smaller compared to benzodiazepines, and long-term and relapse prevention data are limited [19,23]

- May be considered an alternative in patients for whom benzodiazepines are contraindicated (e.g., history of substance use disorder, need for long-term treatment, older adults at risk of falls) [4]

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 7.5 mg twice daily or 5 mg three times daily [1]

- Titration: Increase by 5 mg/day every 2–3 days as needed [1]

- Target dose: 20–30 mg/day in divided doses [1]

- Maximum dose: 60 mg/day [1]

- BID vs TID: Twice-daily schedules can be used for convenience; comparative data suggest similar efficacy with potentially improved tolerability/adherence for some patients [24]

- Clinical considerations

- Clinical effects typically take 2–4 weeks to emerge; not suitable for acute or PRN anxiety relief [4]

- Non-sedating/non-habit-forming alternative due to lack of GABA activity; does not block benzodiazepine withdrawal—taper benzodiazepines gradually if switching [1,25,26]

- Prior benzodiazepine use may predict reduced response; patients with recent use (<1 month) had higher dropout rates and more adverse events [13,27]

- Possible explanations include subclinical benzodiazepine withdrawal, differing patient expectations regarding onset and sedation [13,27]

Off-Label Uses

Unipolar Depression Augmentation

- Buspirone is used off-label as an augmentation strategy for patients with inadequate response to SSRIs, though supporting evidence is limited [5,28]

- The STAR* D trial compared augmentation with bupropion-SR versus buspirone in patients who failed to remit on citalopram [5]

- Remission rates were similar between groups:

- HRSD-17: 30% vs. 30%

- QIDS-SR-16: 33% vs. 39% [5]

- However, bupropion was associated with greater symptom reduction and better tolerability [5]

- In anxious depressed patients, bupropion augmentation showed higher remission rates than buspirone (18% vs. 9%) [29]

- Remission rates were similar between groups:

- Placebo-controlled evidence is less supportive [28]

- Two double-blind RCTs of buspirone augmentation in SSRI nonresponders failed to show significant differences from placebo [6,30]

- High placebo response rates and small sample sizes may have limited the ability to detect a true effect [28]

- A subgroup with severe depression (MADRS >30) may benefit, based on post-hoc analysis of one trial [6]

- Clinical positioning:

- Consider when targeting comorbid anxiety symptoms and when alternatives (e.g., bupropion) are not preferred or tolerated.

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 15–20 mg/day in 2 divided doses

- Titration: May increase every 3–7 days in increments of 10–15 mg/day

- Maximum dose: 60 mg/day in 2–3 divided doses

SSRI-Associated Sexual Dysfunction

- Buspirone has been used off-label to address SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction, but evidence is mixed, so it should be framed as a time-limited trial rather than a reliable intervention [7,8,31]

- Mechanism may involve antagonism of the alpha 2 receptor by buspirone’s active metabolite; 5-HT1A agonism could play a role [31]

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 5–10 mg twice daily

- Target dose: 20–30 mg/day in divided doses; may increase up to 60 mg/day

- Assess response after 2–4 weeks of treatment since response is usually rapid

Social Anxiety Disorder

- Limited and mixed evidence; not recommended as first-line therapy [19,32,33]

Panic Disorder

- Buspirone is not effective for panic disorder and should not be used for this indication [19]

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Evidence is inconclusive; buspirone is not recommended for OCD [34,35]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- No established efficacy; not recommended [34]

Side effects

Buspirone is generally well tolerated; dizziness is the most common adverse effect. Compared with benzodiazepines, it is less sedating and does not cause clinically meaningful psychomotor impairment or physical dependence. Rare but notable adverse events include movement disorders (eg, akathisia) and serotonin syndrome when combined with other serotonergic agents.

Most common side effects

Neurological/Psychiatric

- Dizziness (9-12% incidence) [1,36]

- Most common side effect [37]

- May improve with continued treatment; gradual titration can minimize occurrence

- Headache (6-7% incidence) [38]

- Usually transient and self-limiting, recent meta-analysis showed no significant difference from placebo [37]

- Drowsiness/sedation (9-10% incidence)

- Significantly lower than with benzodiazepines in previous studies [38]

- Meta-analysis suggests rates may not differ meaningfully from placebo [37]

- Does not impair psychomotor or cognitive function in healthy volunteers [36]

- Nervousness (4-5% incidence) [1,38]

- Paradoxical effect that typically resolves with continued treatment

- Light-headedness (4% incidence) [1,38]

- Excitement/agitation (2% incidence) [1,38]

- Paresthesia (2% incidence) [38]

- Confusion (1-2% incidence) [1]

- Insomnia, fatigue, vertigo, and tremor:

- Meta-analysis showed no significant difference from placebo for any of these adverse events [37]

Gastrointestinal

- Nausea (6-8% incidence)

- More common than with some benzodiazepines [38]; meta-analysis showed nausea incidence did not differ significantly from placebo [37]

- Generally mild and transient [39]

- Dry mouth (3% incidence) [1]

- Diarrhea (2-3% incidence)

- Constipation (1-2% incidence)

- Abdominal/gastric distress (1-2% incidence)

Other common side effects

- Fatigue (4-5% incidence) [38]

- Weakness (2% incidence) [1]

- Diaphoresis/sweating (1% incidence) [38]

- Blurred vision (1-2% incidence) [1]

- Tinnitus (1-2% incidence) [1]

- Nasal congestion (1-2% incidence) [1]

- Musculoskeletal pain (1% incidence) [1]

- Sexual side effects

- Buspirone has minimal sexual side effects

- May improve SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction when used as augmentation [7]

Severe side effects

- Movement disorders

- Rare but documented in case reports/series [40]

- Dyskinesia (14 cases), akathisia (10 cases), myoclonus (8 cases), parkinsonism (6 cases), dystonia (6 cases)

- Akathisia

- Hypothesized mechanisms of buspirone-induced akathisia may involve the noradrenergic effects of the 1-PP metabolite

- Risk may be increased when combined with antipsychotics (buspirone increases haloperidol concentrations, though clinical significance is unclear)

- Dyskinesia (including orofacial dyskinesia) has been reported; whether cases represent tardive syndromes vs other drug-induced dyskinesias is often unclear in case reports. [40]

- Rare but documented in case reports/series [40]

- Serotonin syndrome (access the full Serotonin Syndrome Guide)

- Rare when used as monotherapy, but potential risk with serotonergic combinations [41]

- Contraindicated with MAOIs, including linezolid and IV methylene blue (14-day washout required) [1]

- Activation of mania/hypomania

- Rare case reports of buspirone-induced mania [42]

- Use with caution in patients with bipolar disorder

- Worsening of psychosis

- Very rare; case reports in patients with underlying psychotic disorders [43,44]

- Sleepwalking (somnambulism)

- Postmarketing reports of new-onset sleepwalking associated with buspirone [45]

- Mechanism unclear; consider underlying psychiatric comorbidities

- QT prolongation

- Reported in patients with preexisting cardiac disorders [46]

- Clinical significance in patients without cardiac disease remains unclear

- Consider ECG monitoring in patients with known cardiac conditions or risk factors

- Discontinuation considerations

- Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone is not associated with physical dependence [47,48]

- Abrupt discontinuation is generally tolerated; tapering can be used to maximize comfort and reduce rebound anxiety from the underlying disorder.

Tolerability considerations

- Cognitive effects

- No significant impairment of psychomotor or cognitive function [36]

- Does not potentiate the effects of alcohol on cognitive/psychomotor performance [49]

- Meta-analysis reported cognitive benefits with buspirone treatment in visual learning, memory, logical reasoning and attention [37]

- Proposed mechanisms may involve

- 5-HT1A receptor activation increases extracellular dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex

- D3 receptor antagonism enhances memory consolidation [37]

- Promotion of hippocampal neurogenesis (preclinical evidence) [37]

- Proposed mechanisms may involve

- Weight effects

- No clinically significant weight gain associated with buspirone use [1]

- Buspirone has a favorable safety profile in overdose [1]

Use in special populations

Pregnancy

- Limited human data overall; due to lack of data, agents other than buspirone are preferred for use during pregnancy [50]

- First-trimester safety:

- Animal reproductive studies showed no evidence of congenital anomalies or teratogenicity [1,51]

- No malformations were observed among 72 infants exposed to buspirone during the first trimester with or without other psychotropic medications according to the MGH National Pregnancy Registry for Psychiatric Medications [52]

Breastfeeding

- Human lactation data are limited; labeling recommends avoiding buspirone during breastfeeding if clinically possible [1]

- Limited data indicate low levels of buspirone in breast milk. Product labeling reported buspirone and its metabolites were excreted in rat milk

Hepatic impairment

- Use is not recommended as per product labelling [1]

- Severe hepatic impairment constitutes a contraindication in Canadian labelling [53]

- Buspirone undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism; AUC increased 10- to 20-fold and half-life doubled to tripled in patients with cirrhosis compared to healthy controls [1,54]

Renal impairment

- CrCl ≥60 mL/minute:

- No dosage adjustment necessary

- In patients with mild to moderate renal impairment, the pharmacokinetics of buspirone and its active metabolite 1-PP are similar to those in individuals with normal renal function [55]

- CrCl <60 mL/minute:

- Start with low daily doses (e.g., 5 mg twice daily) [15,55]

- Titrate cautiously based on response and tolerability with close monitoring for adverse effects

- Hemodialysis:

- 86% of buspirone is protein-bound, which makes it unlikely to be dialyzable

- Start at 2.5–5 mg twice daily; limit total daily dose to 30–45 mg/day [15,55]

- Canadian labeling contraindicates use in severe renal impairment [53]

Elderly

- No routine dosage adjustment is needed [1]

- No effects of age on pharmacokinetics were observed

Brand names

- US: Bucapsol, BuSpar (discontinued), BuSpar Dividose (discontinued), Vanspar

- Canada: AMB-Buspirone, APO-BusPIRone, AURO-Buspirone, CO BusPIRone, JAMP-Buspirone, MINT-Buspirone, PMS-BusPIRone, Pro-Buspirone, TEVA-BusPIRone

- Other countries/regions: Actium, Anchocalm, Anksilon, Ansial, Ansionax, Ansitec, Ansiten, Anxbeat, Anxinil, Anxiolan, Anxiron, Anxut, Apo-Buspirone, Aristopiron, Axoren, Babron, Barpil, Benzodep, Bergamol, Bespar, Biron, Biziron, Bonival, Boronex, Boryung buspar, Buisline, Busansil, Buscalm, Buscalma, Busirone, Buslac, Busmin, Busone, Busp, Buspam, Buspalex, Buspanil, Buspar, Buspar First Month, Busparium, Buspin, Buspimen, Buspine, Buspinet, Buspirona, Buspirona Labesfal, Buspirona orion, Buspirol, Buspiron, Buspiron 2care4, Buspiron Actavis, Buspiron alpharma, Buspiron ebb, Buspiron Hcl Actavis, Buspiron hcl alpharma, Buspiron hcl cf, Buspiron hcl merck, Buspiron HCl Sandoz, Buspiron hexal, Buspiron Mylan, Buspiron ratiopharm, Buspirone, Buspirone cox, Buspirone g gam, Buspirone HCL, Buspirone kent, Buspirone merck, Buspirone Orion, Buspirone Sandoz, Busporone, Buspro, Busron, Busta, Buxal, Cloridrato de buspirona, Dalpas, Depiron, Duvaline, Effiplen, Epsilat, Establix, Etex buspirone, Exan, Exupar, Hiremon, Hobatstress, Itagil, Komasin, Lanamont, Lebilon, Ledion, Loxapin, Mabuson, Myungin buspirone hcl, Nadrifor, Narol, Nervostal, Neurobus, Nevrorestol, Nitil, Nodeprex, Norbal, Normaton, Novatil, Pasrin, Paxon, Pendium, Piron, Pms buspirone, Psibeter, Qi bi te, Relac, Relax, Samsung buspirone, Sbrol, Sburol, Sepirone, Serenid, Seron, Sorbon, Spamilan, Spir, Spitomin, Stressigal, Su xin, Suxin, Svitalark, Tamspar, Tensispes, Tran-q, Tutran, Umolit, Vespireit, Vurinil, Whanin buspirone, Xiety, Yi shu, Young poong buspirone

References

1. Food & Drug Administration. (2010). BuSpar® (buspirone HCl, USP) tablets prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/018731s051lbl.pdf

2. Loane, C., & Politis, M. (2012). Buspirone: What is it all about? Brain Research, 1461, 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2012.04.032

3. Tunnicliff, G. (1991). Molecular basis of buspirone’s anxiolytic action. Pharmacology & Toxicology, 69(3), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0773.1991.tb01289.x

4. Howland, R. H. (2015). Buspirone: Back to the Future. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 53(11), 21–24. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20151022-01

5. Trivedi, M. H., Fava, M., Wisniewski, S. R., Thase, M. E., Quitkin, F., Warden, D., Ritz, L., Nierenberg, A. A., Lebowitz, B. D., Biggs, M. M., Luther, J. F., Shores-Wilson, K., & Rush, A. J. (2006). Medication Augmentation after the Failure of SSRIs for Depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(12), 1243–1252. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa052964

6. Appelberg, B. G., Syvälahti, E. K., Koskinen, T. E., Mehtonen, O. P., Muhonen, T. T., & Naukkarinen, H. H. (2001). Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(6), 448–452. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v62n0608

7. Landén, M., Eriksson, E., Agren, H., & Fahlén, T. (1999). Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 19(3), 268–271. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004714-199906000-00012

8. Michelson, D., Bancroft, J., Targum, S., Kim, Y., & Tepner, R. (2000). Female sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant administration: A randomized, placebo-controlled study of pharmacologic intervention. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(2), 239–243. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.239

9. McMillen, B. A., & McDonald, C. C. (1983). Selective effects of buspirone and molindone on dopamine metabolism and function in the striatum and frontal cortex of the rat. Neuropharmacology, 22(3), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3908(83)90240-x

10. Lechin, F., van der Dijs, B., Jara, H., Orozco, B., Baez, S., Benaim, M., Lechin, M., & Lechin, A. (1998). Effects of buspirone on plasma neurotransmitters in healthy subjects. Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996), 105(6–7), 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007020050079

11. Berlin, I., Chalon, S., Payan, C., Schöllnhammer, G., Cesselin, F., Varoquaux, O., & Puech, A. J. (1995). Evaluation of the alpha 2-adrenoceptor blocking properties of buspirone and ipsapirone in healthy subjects. Relationship with the plasma concentration of the common metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)-piperazine. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 39(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04443.x

12. Engberg, G. (1989). A metabolite of buspirone increases locus coeruleus activity via alpha 2-receptor blockade. Journal of Neural Transmission, 76(2), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01578749

13. DeMartinis, N., Rynn, M., Rickels, K., & Mandos, L. (2000). Prior benzodiazepine use and buspirone response in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(2), 91–94. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v61n0203

14. Mahmood, I., & Sahajwalla, C. (1999). Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of buspirone, an anxiolytic drug. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 36(4), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199936040-00003

15. Barbhaiya, R. H., Shukla, U. A., Pfeffer, M., Pittman, K. A., Shrotriya, R., Laroudie, C., & Gammans, R. E. (1994). Disposition kinetics of buspirone in patients with renal or hepatic impairment after administration of single and multiple doses. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 46(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00195914

16. Kivistö, K. T., Lamberg, T. S., Kantola, T., & Neuvonen, P. J. (1997). Plasma buspirone concentrations are greatly increased by erythromycin and itraconazole. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 62(3), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90038-2

17. Lilja, J. J., Kivistö, K. T., Backman, J. T., Lamberg, T. S., & Neuvonen, P. J. (1998). Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 64(6), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90056-X

18. BucapsolTM (buspirone hydrochloride) capsules. (2025). Pangea Pharmaceuticals LLC. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=f101c5f3-d533-474d-a8bf-90d054933d16&type=display#ID_2f628fb1-d49b-4748-adf8-f6f803a92f21

19. Bandelow, B., Allgulander, C., Baldwin, D. S., Costa, D. L. da C., Denys, D., Dilbaz, N., Domschke, K., Eriksson, E., Fineberg, N. A., Hättenschwiler, J., Hollander, E., Kaiya, H., Karavaeva, T., Kasper, S., Katzman, M., Kim, Y.-K., Inoue, T., Lim, L., Masdrakis, V., … Zohar, J. (2023). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders – Version 3. Part I: Anxiety disorders. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry: The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, 24(2), 79–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2022.2086295

20. Gammans, R. E., Stringfellow, J. C., Hvizdos, A. J., Seidehamel, R. J., Cohn, J. B., Wilcox, C. S., Fabre, L. F., Pecknold, J. C., Smiths, W. T., & Rickels, K. (2008). Use of Buspirone in Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Coexisting Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis of Eight Randomized, Controlled Studies. Neuropsychobiology, 25(4), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1159/000118837

21. Garakani, A., Murrough, J. W., Freire, R. C., Thom, R. P., Larkin, K., Buono, F. D., & Iosifescu, D. V. (2020). Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment Options. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 595584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.595584

22. Abejuela, H. R., & Osser, D. N. (2016). The Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Program: An Algorithm for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 24(4), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000098

23. Chessick, C. A., Allen, M. H., Thase, M. E., Batista Miralha da Cunha, A. A., Kapczinski, F., Silva de Lima, M., & dos Santos Souza, J. J. (2006). Azapirones for generalized anxiety disorder. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006(3), CD006115. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006115

24. Sramek, J. J., Frackiewicz, E. J., & Cutler, N. R. (1997). Efficacy and safety of two dosing regimens of buspirone in the treatment of outpatients with persistent anxiety. Clinical Therapeutics, 19(3), 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80134-8

25. Sramek, J. J., Hong, W. W., Hamid, S., Nape, B., & Cutler, N. R. (1999). Meta-analysis of the safety and tolerability of two dose regimens of buspirone in patients with persistent anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 9(3), 131–134. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10356651

26. Rickels, K., Schweizer, E., Csanalosi, I., Case, W. G., & Chung, H. (1988). Long-term Treatment of Anxiety and Risk of Withdrawal: Prospective Comparison of Clorazepate and Buspirone. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45(5), 444–450. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800290060008

27. Schweizer, E., Rickels, K., & Lucki, I. (1986). Resistance to the anti-anxiety effect of buspirone in patients with a history of benzodiazepine use. The New England Journal of Medicine, 314(11), 719–720. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198603133141121

28. Rafeyan, R., Papakostas, G. I., Jackson, W. C., & Trivedi, M. H. (2020). Inadequate Response to Treatment in Major Depressive Disorder: Augmentation and Adjunctive Strategies. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 81(3), OT19037BR3. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.OT19037BR3

29. Fava, M., Rush, A. J., Alpert, J. E., Balasubramani, G. K., Wisniewski, S. R., Carmin, C. N., Biggs, M. M., Zisook, S., Leuchter, A., Howland, R., Warden, D., & Trivedi, M. H. (2008). Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: A STAR*D report. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868

30. Landén, M., Björling, G., Agren, H., & Fahlén, T. (1998). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of buspirone in combination with an SSRI in patients with treatment-refractory depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(12), 664–668. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9921700

31. Lipman, K., Betterly, H., & Botros, M. (2024). Improvement in Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor-Associated Sexual Dysfunction With Buspirone: Examining the Evidence. Cureus, 16(4), e57981. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.57981

32. van Vliet, I. M., den Boer, J. A., Westenberg, H. G., & Pian, K. L. (1997). Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia: A double-blind placebo-controlled study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 58(4), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v58n0405

33. Van Ameringen, M., Mancini, C., & Wilson, C. (1996). Buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in social phobia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 39(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(96)00030-4

34. Bandelow, B., Allgulander, C., Baldwin, D. S., Costa, D. L. da C., Denys, D., Dilbaz, N., Domschke, K., Hollander, E., Kasper, S., Möller, H.-J., Eriksson, E., Fineberg, N. A., Hättenschwiler, J., Kaiya, H., Karavaeva, T., Katzman, M. A., Kim, Y.-K., Inoue, T., Lim, L., … Zohar, J. (2023). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders – Version 3. Part II: OCD and PTSD. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry: The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, 24(2), 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2022.2086296

35. Garg, K., & Tyagi, H. (2021). Buspirone in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A potential dark horse? BJPsych Open, 7(S1), S165–S165. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.457

36. O’Hanlon, J. F. (1991). Review of buspirone’s effects on human performance and related variables. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 1(4), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/0924-977X(91)90002-C

37. Du, Y., Li, Q., Dou, Y., Wang, M., Wang, Y., Yan, Y., Fan, H., Yang, X., & Ma, X. (2024). Side effects and cognitive benefits of buspirone: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon, 10(7), e28918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28918

38. Newton, R. E., Marunycz, J. D., Alderdice, M. T., & Napoliello, M. J. (1986). Review of the side-effect profile of buspirone. The American Journal of Medicine, 80, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(86)90327-X

39. Gammans, R. E., Mayol, R. F., & LaBudde, J. A. (1986). Metabolism and disposition of buspirone. The American Journal of Medicine, 80, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(86)90331-1

40. Rissardo, J. P., & Caprara, A. L. F. (2020). Buspirone-associated Movement Disorder: A Literature Review. Prague Medical Report, 121(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.14712/23362936.2020.1

41. Manos, G. H. (2000). Possible serotonin syndrome associated with buspirone added to fluoxetine. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 34(7–8), 871–874. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.19341

42. McIvor, R. J., & Sinanan, K. (1991). Buspirone-induced mania. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 158(1), 136–137. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.158.1.136

43. Apeldoorn, S., Chavez, R., Haschemi, F., Elsherif, K., Weinstein, D., & Torrico, T. (2023). Worsening psychosis associated with administrations of buspirone and concerns for intranasal administration: A case report. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1129489. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1129489

44. Pantelis, C., & Barnes, T. R. (1993). Acute exacerbation of psychosis with buspirone? Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 7(3), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/026988119300700311

45. Moses, T. E. H., & Javanbakht, A. (2022). New-Onset Sleepwalking in a Patient Treated With Buspirone. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 42(1), 96–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001476

46. Stock, E. M., Zeber, J. E., McNeal, C. J., Banchs, J. E., & Copeland, L. A. (2018). Psychotropic Pharmacotherapy Associated With QT Prolongation Among Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 52(9), 838–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028018769425

47. Sellers, E. M., Schneiderman, J. F., Romach, M. K., Kaplan, H. L., & Somer, G. R. (1992). Comparative drug effects and abuse liability of lorazepam, buspirone, and secobarbital in nondependent subjects. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 12(2), 79–85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1573044

48. Griffith, J. D., Jasinski, D. R., Casten, G. P., & McKinney, G. R. (1986). Investigation of the abuse liability of buspirone in alcohol-dependent patients. The American Journal of Medicine, 80, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(86)90329-3

49. Rush, C. R., & Griffiths, R. R. (1997). Acute participant-rated and behavioral effects of alprazolam and buspirone, alone and in combination with ethanol, in normal volunteers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 5(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.5.1.28

50. Thorsness, K. R., Watson, C., & LaRusso, E. M. (2018). Perinatal anxiety: Approach to diagnosis and management in the obstetric setting. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 219(4), 326–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.017

51. Kai, S., Kohmura, H., Ishikawa, K., Ohta, S., Kuroyanagi, K., Kawano, S., Kadota, T., Chikazawa, H., Kondo, H., & Takahashi, N. (1990). [Reproductive and developmental toxicity studies of buspirone hydrochloride (II)–Oral administration to rats during perinatal and lactation periods]. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences, 15 Suppl 1, 61–84. https://doi.org/10.2131/jts.15.supplementi_61

52. Freeman, M. P., Szpunar, M. J., Kobylski, L. A., Harmon, H., Viguera, A. C., & Cohen, L. S. (2022). Pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to buspirone: Prospective longitudinal outcomes from the MGH National Pregnancy Registry for Psychiatric Medications. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25(5), 923–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01250-8

53. TEVA-BUSPIRONE Buspirone Hydrochloride Tablets. (2023). Teva Canada Limited. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00073925.PDF

54. Dalhoff, K., Poulsen, H. E., Garred, P., Placchi, M., Gammans, R. E., Mayol, R. F., & Pfeffer, M. (1987). Buspirone pharmacokinetics in patients with cirrhosis. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 24(4), 547–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03210.x

55. Caccia, S., Vigano, G. L., Mingardi, G., Garattini, S., Gammans, R. E., Placchi, M., Mayol, R. F., & Pfeffer, M. (1988). Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Oral Buspirone in Patients with Impaired Renal Function. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 14(3), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-198814030-00005