In a nutshell

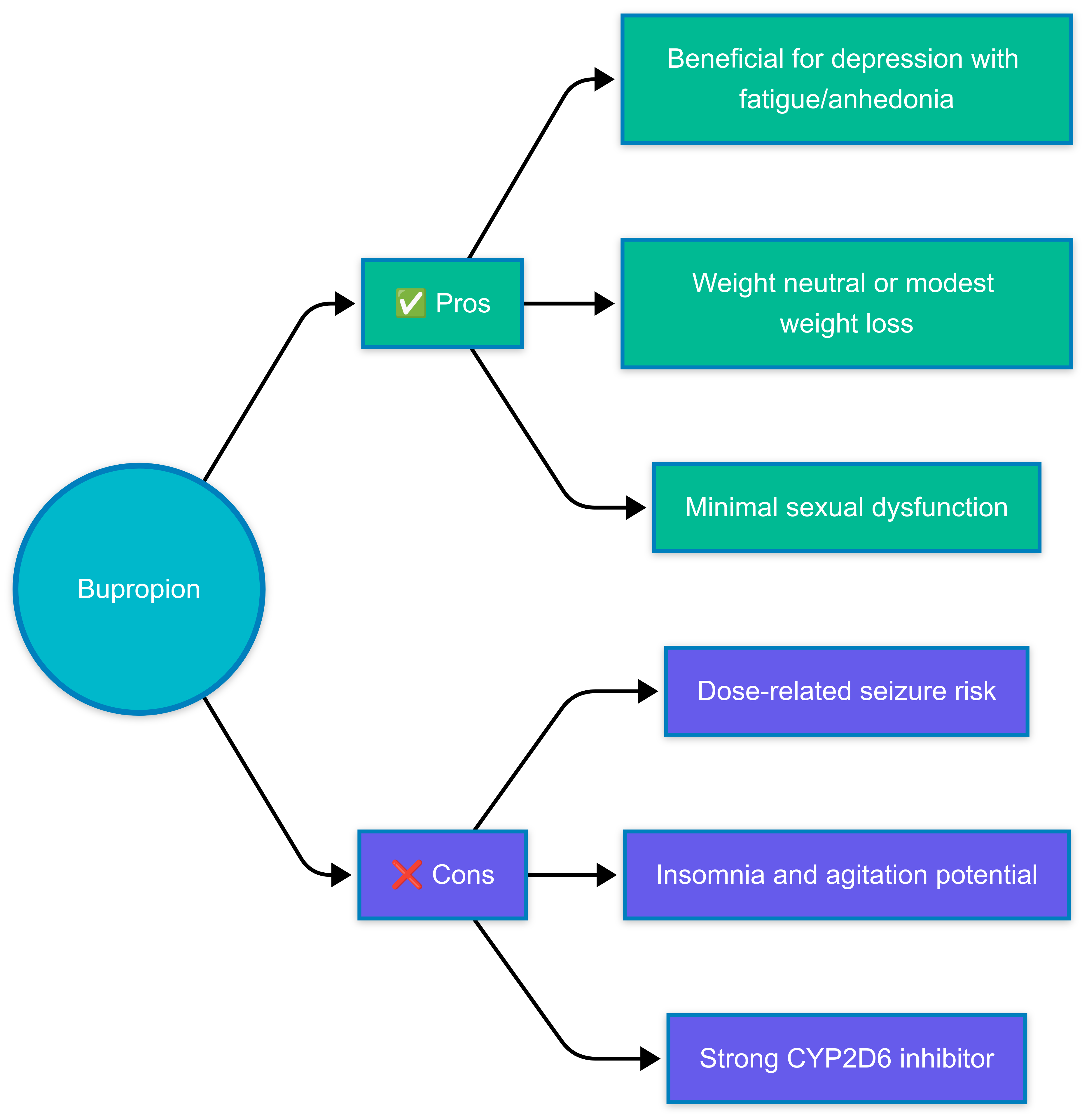

Bupropion is a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor without significant serotonergic effects. It may be particularly useful for patients whose depression is associated with fatigue, poor concentration, or anhedonia. Its favorable profile regarding sexual dysfunction and weight makes it an appealing option when these issues are a concern. The seizure risk, while dose-related and manageable for most patients when dosed appropriately, requires consideration in at-risk populations. Similarly, the potential for insomnia and anxiety may limit its use in certain patients, though traditional concerns about using bupropion in anxious patients have been challenged (See Indications, Major depressive disorder).

- Choosing bupropion over other antidepressants:

- Depression with prominent fatigue, lack of energy, or anhedonia

- Concerns about sexual dysfunction or weight gain

- Need for smoking cessation

- Seasonal affective disorder prevention

- SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction

- Prefer alternatives if:

- Patients with seizure risk factors (see Side effects section below)

- Significant insomnia or agitation, though evidence shows bupropion provides comparable improvement in comorbid anxiety symptoms and similar rates of activation side effects as SSRIs (See Side effects)

- Patients with eating disorders, especially bulimia

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

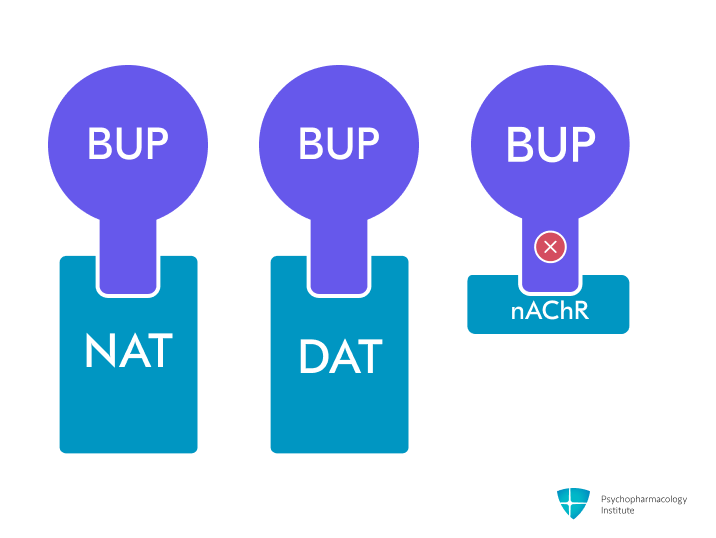

- Primary mechanism: Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibition (NDRI) through NET and DAT blockade [1]

- Does not affect serotonin reuptake and has no significant activity at serotonergic, adrenergic, muscarinic, and histaminergic receptors [2]

- Lower risk of sexual dysfunction and weight gain compared to other antidepressants [1,3]

- Dopaminergic effects

- Weak dopamine reuptake inhibition compared to stimulants [4]

- Unlike amphetamines, it does not act as a dopamine-releasing agent [4]

- May explain efficacy in depression with prominent anhedonia and fatigue [5]

- Blockade of dopamine reuptake in the mesolimbic dopamine system may explain part of the efficacy in smoking cessation [6]

- Noradrenergic effects

- Norepinephrine reuptake inhibition is approximately 10-fold weaker than dopamine effects [2]

- May contribute to its therapeutic effects in depression and ADHD [7,8]

- Nicotinic receptor antagonism

- Non-competitive antagonist of α3β4 nicotinic receptors [1,9]

- The active metabolite hydroxybupropion is a more potent non-competitive antagonist of α4β2 receptors [1,9]

- This mechanism probably plays a role in its efficacy for smoking cessation [9]

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism

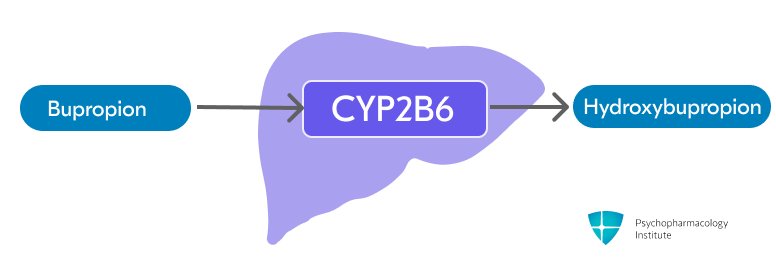

- Bupropion is extensively metabolized in the liver through CYP2B6 to form active metabolite hydroxybupropion (primary pathway) [1]

- Threohydrobupropion and erythrohydrobupropion are formed through non-CYP-mediated metabolism (secondary pathway)

- Active metabolites exhibit long half-lives but 20% to 50% of the potency of bupropion.

- Bupropion levels potentially increased by:

- CYP2B6 inhibitors

- Ticlopidine and clopidogrel

- Consider dose reduction when using strong CYP2B6 inhibitors

- CYP2B6 inhibitors

- Bupropion levels potentially decreased by:

- CYP2B6 inducers

- Carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin

- Ritonavir, lopinavir, efavirenz

- Consider dose increase but do not exceed the maximum recommended dose [10]

- CYP2B6 inducers

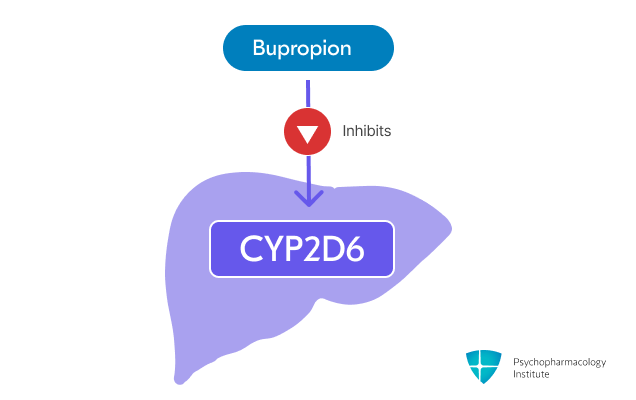

- Bupropion is a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor [10]

- May increase levels of CYP2D6 substrates, including:

- Antidepressants (venlafaxine, duloxetine, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline)

- Vortioxetine dose should be reduced by 50% when used with bupropion. Consider alternative options.

- Antipsychotics (haloperidol, risperidone, aripiprazole)

- Beta-blockers (metoprolol)

- Type 1C antiarrhythmics (propafenone, flecainide)

- Antidepressants (venlafaxine, duloxetine, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline)

- Consider dose reduction of CYP2D6 substrates when used concomitantly

- Bupropion may reduce the efficacy of prodrugs requiring CYP2D6 activation, such as tamoxifen. Patients treated concomitantly may require increased doses of the drug.

- May increase levels of CYP2D6 substrates, including:

- Important drug interactions

- Contraindicated with MAOIs

- A 14-day washout period is required when switching to/from MAOIs

- Use caution with dopaminergic drugs (levodopa, amantadine) due to potential CNS toxicity [10]

- Contraindicated with MAOIs

- Note: Bupropion may cause false-positive urine test results for amphetamines [11,12]

Half-life

- Bupropion’s half-life is approximately 21 (12 to 30) hours, and it is prolonged in renal and hepatic failure

- Active metabolites half-life (after a single dose)

- Hydroxybupropion: 20 ± 5 hours

- Erythrohydrobupropion: 33 ± 10 hours

- Threohydrobupropion: 37 ± 13 hours

- While bupropion’s long half-life provides steady therapeutic effects, gradual dose titration is recommended to reduce seizure risk [10,13]

Dosage forms

Dosage forms

- Immediate-release

- Tablets

- 75 mg, 100 mg

- Generic, Wellbutrin

- Tablets

- Sustained-release (12-hour)

- Tablets

- 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg

- Generic, Wellbutrin SR

- Tablets

- Extended-release (24-hour)

- Tablets (hydrochloride salt)

- 150 mg, 300 mg, 450 mg

- Generic, Wellbutrin XL, Forfivo XL (450 mg only)

- Tablets (hydrobromide salt)

- Not interchangeable on a mg-per-mg basis with hydrochloride formulations.

- 174 mg, 348 mg, 522 mg (equivalent to 150 mg, 300 mg, 450 mg HCl)

- Aplenzin

- Tablets (hydrochloride salt)

Formulation practicalities

- The extended-release formulation is the preferred option for most patients.

- This is due to its once-daily dosing, stable blood levels, and lowest peak concentrations, which may reduce seizure risk [7,14]

- All formulations should be swallowed whole; do not crush, chew, or divide.

- The insoluble shell of extended-release tablets may remain intact during GI transit and be eliminated in the feces.

- Extended Release (XL/XR)

- Dosing frequency: Once daily

- Maximum single dose: 450 mg

- The preferred formulation for most patients

- Can be given once daily in the morning to minimize sleep disruption [14]

- Sustained Release (SR)

- Dosing frequency: Twice daily

- Requires at least 8 hours between successive doses

- Maximum single dose: 200 mg

- Provides intermediate convenience between IR and XL formulations with twice-daily dosing [3,7]

- Immediate Release (IR)

- Dosing frequency: 3-4 times daily

- Requires at least 6 hours between successive doses

- Maximum single dose: 150 mg

- Higher peak serum levels with greater fluctuations, potentially increasing seizure risk and requiring more frequent dosing [7]

- Rarely used, except in cost-constrained settings or when titration flexibility is required (e.g., elderly patients) [7]

- Converting between formulations

- When switching formulations, maintain the same total daily dose [10]

- Adjust only the dosing frequency based on the formulation characteristics.

- Conversion example: 100 mg IR three times daily = 150 mg SR twice daily = 300 mg XL once daily

- Gradual dose titration is recommended with all formulations to reduce seizure risk [10,13]

Indications

FDA-Approved Indications

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

- First-line antidepressant treatment option for MDD [15]

- It may be particularly useful for patients whose depression manifests with fatigue [16] and poor concentration [17]

- Favorable sexual function profile and weight neutrality position it as a valuable first-line option when these issues are a concern [15]

- In the STAR-D trial, adding bupropion to citalopram resulted in higher remission rates for anxious patients compared to augmentation with buspirone (18% vs. 9%) [18]

- Dosing:

- While bupropion’s long half-life provides steady therapeutic effects, gradual dose titration is recommended to reduce seizure risk [10,13]

- Extended-release (XL)

- Hydrochloride salt

- Starting dose: 150 mg once daily in the morning

- Target dose: 300 mg once daily after 4 days

- Maximum: 450 mg once daily

- Hydrobromide salt

- Starting dose: 174 mg once daily in the morning

- Target dose: 348 mg once daily after 4 days

- Maximum: 522 mg once daily

- Hydrochloride salt

- Sustained release (SR)

- Starting dose: 150 mg once daily in the morning

- Target dose: 150 mg twice daily after 3 days

- Maximum dose: 200 mg twice daily (no single dose>200 mg)

- Immediate release

- Starting dose: 100 mg twice daily

- Target dose: 100 mg three times daily after 3 days

- Maximum dose: 450 mg/day in 3 or 4 divided doses (no single dose >150 mg)

Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) Prevention (XL formulation only)

- Bupropion extended-release is the only FDA-approved antidepressant with prophylactic efficacy for SAD [19]. While effective, the benefits vary among patients, with moderate-quality evidence supporting its use [20]

- Not all patients benefit equally; clinical response and side effect risks should be carefully considered [21]

- Reserve preventive treatment for patients with a history of recurrent seasonal episodes or marked functional impairment.

- Initiate treatment in the autumn, prior to the onset of depressive symptoms

- Continue through the winter season

- Taper and discontinue in early spring with a dose reduction to 150 mg once daily before discontinuing

- Dosing

- Initial: 150 mg XL once daily

- Target dose: May increase to 300 mg once daily, after 7 days

- Maximum dose: 300 mg. Doses above 300 mg were not assessed in the SAD trials [10]

Smoking Cessation

- Bupropion SR is the only formulation of bupropion that is FDA-approved for smoking cessation

- While Zyban (bupropion SR) was discontinued in 2022, generic SR formulations remain available for smoking cessation; evidence suggests XL formulations may be equally effective [14]

- Can be used as monotherapy or in combination with nicotine replacement therapy [22]

- Treatment timing

- Begin at least 1 week before the target quit date

- If successful, continue for at least 12 weeks [23]

- May extend up to 1 year for relapse prevention in select cases [24]

- Consider discontinuation if no significant progress by week 7 [24]

- Dosing

- Starting dose: 150 mg/day for 3 days

- Target dose: 150 mg twice daily

- Maximum dose: 300 mg/day

- For poor tolerability: May continue 150 mg/day, which has proven efficacy [25]

Off-Label Uses

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Not recommended as first-line therapy in ADHD [26]

- Shows moderate efficacy in ADHD, with clinical effects taking several weeks to appear.

- Meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials showed higher response rates compared to placebo [27]

- May offer a modest benefit for patients with comorbid depression or substance use disorders, but more research is needed due to methodological caveats [28,29]

- Less effective than stimulants based on indirect comparisons of effect sizes, though no direct head-to-head trials exist [30]

- Dosing:

- SR formulation

- Starting dose: 100 mg/day in the morning

- After 1 week titrate to 100 mg twice daily

- Target dose: May increase to 100-150 mg twice daily based on response

- Maximum dose: 400 mg/day [8]

- XL formulation

- Starting dose: 150 mg/day in the morning for one week

- Target dose: 300 mg/day for 3 weeks

- Maximum dose: 450 mg/day

- SR formulation

Sexual Dysfunction (SSRI-induced)

- Effective both as an augmentation to SSRIs or as monotherapy after SSRI discontinuation [31,32]

- Consider a watchful waiting period (2-8 weeks) before the intervention, as dysfunction may remit spontaneously [31]

- Augmentation

- SR formulation

- Starting dose: 150 mg/day

- Target dose: 150 mg twice daily after 2-4 weeks, based on response

- May increase sooner (after 3 days) if needed and tolerated [32]

- Maximum dose: 200 mg twice daily after an additional 2-4 weeks [32]

- XL formulation

- Starting dose: 150 mg/day

- Target dose: 300 mg once daily after 2-4 weeks, based on response

- May increase sooner (after 4 days) if needed and tolerated [10]

- Maximum dose: 450 mg once daily after additional 2-4 weeks

- SR formulation

- For switching to monotherapy

- Cross-taper over 1-2 weeks while initiating bupropion

- Titrate bupropion to a therapeutic dose based on indication and response [33,34]

Bipolar Depression

- Proposed as a second-line add-on treatment with lithium/divalproex or an atypical antipsychotic [35]

- Avoided or use cautiously in patients with a history of antidepressant-induced mania, current or predominant mixed features, or recent rapid cycling [36]

- Despite early studies suggesting otherwise, current evidence shows manic/hypomanic switching rates similar to other antidepressants [37]

- Dosing:

- Recommendations derived primarily from studies using the SR formulation [38]

- Starting dose: 100 mg once daily with mood stabilizer

- Titration: Increase at 2-week intervals based on response and tolerability

- Target dose: 250 mg/day (average effective dose in clinical trials)

- Maximum dose: 450 mg/day in two divided doses

Combination Products

- Contrave (naltrexone/bupropion)

- FDA-approved for chronic weight management [39]

- For adults with:

- Initial BMI ≥30 kg/m², or

- BMI ≥27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbidity (e.g., hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia) [40]

- Used as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity [41]

- Dosing

- Each tablet contains naltrexone 8 mg/bupropion 90 mg

- Start with one tablet daily, increase by one tablet weekly to reach the target dose of two tablets twice daily by Week 4.

- Maximum dose: naltrexone 32 mg/bupropion 360 mg (four tablets daily)

Side Effects

Most common side effects

Neurological/Psychiatric

- Insomnia (11-40% incidence)

- Most common side effect [7]

- Dose and timing-dependent

- Can be minimized by morning dosing and avoiding late afternoon doses, particularly with SR/XL formulations [7]

- Generally improves with continued treatment [42,43]

- Agitation/Anxiety (2-32% incidence) [10,44]

- Although bupropion may induce anxiety in some cases, evidence shows it provides comparable improvement in comorbid anxiety symptoms and similar rates of activation side effects (e.g., insomnia) as SSRIs [45]

- More common during the first few weeks, but may persist hronically for a minority of patients [43]

- Consider lower starting doses in anxiety-prone patients [43,46].

- Headache (up to 34% incidence)

- Dizziness (6% to 22% incidence)

- Tremor (1-21% incidence)

Gastrointestinal

- Dry mouth (10-28% incidence)

- Nausea/vomiting (9-23% incidence)

- Can be minimized by taking it with food [47]

- Generally transient [1,42]

- Constipation (8-26% incidence) [10]

- Weight loss (14-28% incidence)

- More pronounced than with SSRIs [48]

- Dose-dependent effect [10]

- May be beneficial in patients where weight gain is a concern

- Monitor in underweight patients [7]

Other common side effects

- Tachycardia (11% incidence)

- Hypertension (2% incidence in SAD trials)

- Clinical trial data suggests no significant difference from placebo in patients with pre-existing mild hypertension [7,49]

- Risk increases when combined with nicotine replacement [10]

- Consider blood pressure assessment primarily in high-risk patients or when used with nicotine replacement [7]

- Antidepressant-induced excessive sweating (ADIES)

- Incidence 5% to 22% [10,50]

- Consider switching to an SSRI [51]

- Terazosin and oxybutynin have shown efficacy in reducing ADIES [52,53]

Severe side effects

- Seizures

- Contraindicated in current or past epilepsy and low threshold for seizures [1]

- Risk is dose-dependent and formulation-dependent [1,54]

- Highest seizure risk profile among antidepressants [55]

- Seizure risk: Bupropion (>2x risk, OR = 2.23) > SSRIs (OR = 1.76) > SNRIs (OR = 1.40) ≈ Mirtazapine (OR = 1.38)

- Incidence by formulation and dose [7,55]

- IR: 0.4% at 300-450mg/day; 4% at 450-600mg/day

- SR/XL: 0.1% at 100-300mg/day; 0.4% at 400mg/day [55]

- Lower peak concentrations may further reduce seizure risk [54]

- Seizure incidence increases almost tenfold between 450–600 mg/day [10]

- Limit bupropion XL to ≤450 mg/day and titrate gradually to minimize risk

- Risk factors

- History of seizures

- Eating disorders

- Electrolyte/metabolic disturbances

- Abrupt discontinuation of alcohol or sedatives

- Head trauma

- CNS tumors or conditions with high seizure risk (e.g. arteriovenous malformation, stroke)

- Higher doses/overdoses ( >400 mg/day) and use of IR formulation [7]

- Medications that lower seizure threshold [10]

- Activation of mania/hypomania

- While early studies suggested lower mania/hypomania risk with bupropion, current evidence indicates switch rates comparable to other antidepressants [37]

- Psychosis/paranoia

- Rare but reported, especially in patients with risk factors like substance use, older age, or history of head trauma [56]

- Angle-closure glaucoma

- Pupilar dilation induced by bupropion may trigger angle-closure attack in a patients with anatomically narrow angles [10,57]

- Hypersensitivity reactions

- Ranging from pruritus and urticaria to life-threatening conditions (anaphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) [58]

- Consider immediate discontinuation and medical attention upon first allergic symptoms [10]

- Delayed hypersensitivity reactions to bupropion can manifest as serum sickness, including arthralgia, myalgia, fever, and rash [59]

- Ranging from pruritus and urticaria to life-threatening conditions (anaphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) [58]

- Abuse potential

- Bupropion is the most commonly misused antidepressant, with 75% increase in abuse between 2000-2012; particularly prevalent in correctional facilities where it’s known as “poor man’s cocaine” [60–62]

- Intranasal insufflation (crushing and snorting) is the most common method of abuse (50% of cases), producing cocaine-like euphoric effects by bypassing first-pass metabolism; seizures are the most common serious adverse effect (36% of cases) [63]

Use in special populations

Pregnancy

- First-trimester safety:

- Systematic reviews and manufacturer data found no increased risk of malformations, impact on birthweight, or gestational age compared to the general population [64,65]

- While some individual studies have reported cardiac abnormalities [66,67], a study that adjusted for depression severity showed no increase in cardiac malformations [68]

- Pregnancy outcomes:

- Bupropion exposure during pregnancy was not associated with poor neonatal adaptation [69]

- Unlike SSRIs, bupropion did not increase the risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension when accounting for maternal depression severity [70]

- Smoking cessation during pregnancy:

- The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found insufficient evidence for bupropion use in pregnancy, with no significant improvement in quit rates compared to placebo in clinical trials [71–73]

Breastfeeding

- Generally considered acceptable during breastfeeding

- Bupropion is present in breast milk, but exposure is low (~2% of the maternal dose) [74]

- Rare case reports of seizure-like episodes in breastfed infants exist, but causality cannot be established [75,76]

- Monitor breastfed infants for:

- Sedation

- Changes in feeding patterns

- Seizure-like activity

Hepatic impairment

- Moderate to severe impairment (Child-Pugh B/C)

- It is not recommended for smoking cessation or SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction; consider alternatives.

- If alternatives are not appropriate, use with extreme caution:

- Immediate release:

- Starting dose: 75 mg every other day

- Titrate no more frequently than every 30 days

- Maximum dose: 75 mg once daily

- 12-hour sustained release:

- Establish tolerability with immediate release first

- Maximum dose: 100 mg once daily or ≤150 mg every other day

- 24-hour extended release:

- Establish tolerability with immediate release first

- Maximum: 150 mg hydrochloride salt or 174 mg hydrobromide salt every other day [10]

- Immediate release:

- Mild impairment (Child-Pugh A/B)

- Starting dose: 50% of the usual indication-specific dose or extend the dosing interval

- May titrate no more frequently than every 14 days

- Do not exceed the indication-specific maximum dose

- Monitor closely for adverse effects

Renal impairment

- CrCl ≥60 mL/minute

- No dosage adjustment is necessary

- CrCl 15-60 mL/minute

- Use with caution

- Consider a maximum daily dose of 150 mg [77]

- CrCl <15 mL/minute or End-Stage Renal Disease

- Alternative agents are preferred

- If necessary:

- Start at 100 mg every 48 hours or 150 mg every 72 hours

- Maximum daily dose: 150 mg [77]

Elderly

- No routine dosage adjustment is needed

- May be at greater risk of drug accumulation during chronic dosing

- Consider lower starting doses and monitor closely [78]

Obesity

- Mean elimination half-life prolonged by 48% in patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m² compared to normal BMI

- Consider an extended washout period when switching to MAOIs in patients with obesity [79]

Brand names

- US: Aplenzin, Forfivo XL, Wellbutrin, Wellbutrin SR, Wellbutrin XL, Zyban (discontinued)

- Canada: MYLAN-BuPROPion XL, ODAN Bupropion SR, TARO-Bupropion XL, TEVA-Bupropion XL, Wellbutrin SR, Wellbutrin XL, Zyban

- Other countries/regions: Addpion SR, Alpes, Alpes XL, Amfebutamone hydrochloride, Anpress SR, Binex bupropion HCL ER, Bromark, Bropion, Budep XR, Budeprion, Buene, Bup, Bupep, Bupiprece SR, Bupion, Bupium, Bupium XL, Bupogran, Bupopin, Bupotel XR, Buproban, Buprinol, Bupropione, Bupropionhydrochlorid, Bupril, Buprion, Buprion SR, Bupress XL, Bupron, Bupron ER, Bupron XL, Bupron-SR, Buropion, Butrew, Butrin, Butrin XL, Butrino XL, Buxon, Carmubine, Clorprax, Cloridrato de bupropiona, Corzen, Depnox, Deprion, Deradop, Duforin, Elontril, Ession ER, Eupropion SR, Eutymia XL, Funnix, Healthpion ER, Healthpion SR, Hupion, Inip, Le fu ting, Mondrian, Nicolift, Niconope ER, Nicopion SR, Noradop, Nordobux, Numax XL, Odranal, Oribion, Papion ER, Paritdam, PMS bupropion, Prewell, Prexaton, Proxiven XL, Qsmok, Quomem, Ravec, Ropion SR, Seth, Smoquit, Stapion SR, Sunbuwell, Trexter, Voxra, Voxra XL, Welard, Welbox, Well, Well SR, Wellben, Wellbutrin (all formulations), Wellviewderma ER, Wrdrop, Xaslexx, Yue ting, Zeropion SR, Zetron, Zetron XL, Ziety, Zupion, Zybex, Zylexx, Zylexx SR, Zylexx XR, Zyntabac

References

- Costa, R., Oliveira, N. G., & Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. (2019). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic of bupropion: Integrative overview of relevant clinical and forensic aspects. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 51(3), 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/03602532.2019.1620763

- Shalabi, A. R., Walther, D., Baumann, M. H., & Glennon, R. A. (2017). Deconstructed Analogues of Bupropion Reveal Structural Requirements for Transporter Inhibition versus Substrate-Induced Neurotransmitter Release. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 8(6), 1397–1403. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00055

- Jefferson, J. W., Pradko, J. F., & Muir, K. T. (2005). Bupropion for major depressive disorder: Pharmacokinetic and formulation considerations. Clinical Therapeutics, 27(11), 1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.11.011

- Bredeloux, P., Dubuc, I., & Costentin, J. (2007). Comparisons between bupropion and dexamphetamine in a range of in vivo tests exploring dopaminergic transmission. British Journal of Pharmacology, 150(6), 711–719. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0707151

- Stahl, S. M., Pradko, J. F., Haight, B. R., Modell, J. G., Rockett, C. B., & Learned-Coughlin, S. (2004). A Review of the Neuropharmacology of Bupropion, a Dual Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(4), 159–166. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC514842/

- Watkins, S. S., Koob, G. F., & Markou, A. (2000). Neural mechanisms underlying nicotine addiction: Acute positive reinforcement and withdrawal. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 2(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200050011277

- Fava, M., Rush, A. J., Thase, M. E., Clayton, A., Stahl, S. M., Pradko, J. F., & Johnston, J. A. (2005). 15 Years of Clinical Experience With Bupropion HCl: From Bupropion to Bupropion SR to Bupropion XL. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 7(3), 106–113. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1163271/

- Wilens, T. E., Spencer, T. J., Biederman, J., Girard, K., Doyle, R., Prince, J., Polisner, D., Solhkhah, R., Comeau, S., Monuteaux, M. C., & Parekh, A. (2001). A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(2), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.282

- Damaj, M. I., Carroll, F. I., Eaton, J. B., Navarro, H. A., Blough, B. E., Mirza, S., Lukas, R. J., & Martin, B. R. (2004). Enantioselective effects of hydroxy metabolites of bupropion on behavior and on function of monoamine transporters and nicotinic receptors. Molecular Pharmacology, 66(3), 675–682. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.104.001313

- Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (2024). WELLBUTRIN XL® (bupropion hydrochloride extended-release) tablets Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/021515s046lbl.pdf

- Casey, E. R., Scott, M. G., Tang, S., & Mullins, M. E. (2011). Frequency of False Positive Amphetamine Screens due to Bupropion Using the Syva Emit II Immunoassay. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 7(2), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-010-0131-5

- Battini, V., Cirnigliaro, G., Giacovelli, L., Boscacci, M., Manzo, S. M., Mosini, G., Guarnieri, G., Gringeri, M., Benatti, B., Clementi, E., Dell’Osso, B., & Carnovale, C. (2023). Psychiatric and non-psychiatric drugs causing false-positive amphetamines urine test in psychiatric patients: A pharmacovigilance analysis using FAERS. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17512433.2023.2211261

- Foley, K. F., DeSanty, K. P., & Kast, R. E. (2006). Bupropion: Pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 6(9), 1249–1265. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.6.9.1249

- Robinson, J. D., Karam-Hage, M., Kypriotakis, G., Beneventi, D., Blalock, J. A., Cui, Y., Gonzalez, R., Tayar, J., Chaftari, P., & Cinciripini, P. M. (2022). Bupropion XL and SR Have Similar Effectiveness and Adverse Event Profiles When Used to Treat Smoking Among Patients at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. The American Journal on Addictions, 31(3), 236–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13282

- Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Adams, C., Bahji, A., Beaulieu, S., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Blumberger, D. M., Brietzke, E., Chakrabarty, T., Do, A., Frey, B. N., Giacobbe, P., Gratzer, D., Grigoriadis, S., Habert, J., Ishrat Husain, M., Ismail, Z., McGirr, A., … Milev, R. V. (2024). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023 : Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can. J. Psychiatry, 69(9), 641–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437241245384

- Pae, C.-U., Lim, H.-K., Han, C., Patkar, A. A., Steffens, D. C., Masand, P. S., & Lee, C. (2007). Fatigue as a core symptom in major depressive disorder: Overview and the role of bupropion. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 7(10), 1251–1263. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.7.10.1251

- Jamerson, B. D., Krishnan, K. R. R., Roberts, J., Krishen, A., & Modell, J. G. (2003). Effect of bupropion SR on specific symptom clusters of depression: Analysis of the 31-item Hamilton Rating Scale for depression. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 37(2), 67–78.

- Fava, M., Rush, A. J., Alpert, J. E., Balasubramani, G. K., Wisniewski, S. R., Carmin, C. N., Biggs, M. M., Zisook, S., Leuchter, A., Howland, R., Warden, D., & Trivedi, M. H. (2008). Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: A STAR*D report. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868

- Belge, J.-B., Sabbe, A. C., & Sabbe, B. G. (2022). When is pharmacotherapy necessary for the treatment of seasonal affective disorder? Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 23(11), 1243–1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2022.2100696

- Gartlehner, G., Nussbaumer‐Streit, B., Gaynes, B. N., Forneris, C. A., Morgan, L. C., Greenblatt, A., Wipplinger, J., Lux, L. J., Noord, M. G. V., & Winkler, D. (n.d.). Second‐generation antidepressants for preventing seasonal affective disorder in adults – Gartlehner, G – 2019 | Cochrane Library. Retrieved January 17, 2025, from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011268.pub3/full

- Hawks, C., Zadounaev, I., Willis, B. J., Hoenig, K., & Holmes, J. (2019). Is bupropion an effective intervention for preventing seasonal affective disorder? Evidence-Based Practice, 22(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.1097/EBP.0000000000000150

- Leone, F. T., Zhang, Y., Evers-Casey, S., Evins, A. E., Eakin, M. N., Fathi, J., Fennig, K., Folan, P., Galiatsatos, P., Gogineni, H., Kantrow, S., Kathuria, H., Lamphere, T., Neptune, E., Pacheco, M. C., Pakhale, S., Prezant, D., Sachs, D. P. L., Toll, B., … Zhu, M. (2020). Initiating Pharmacologic Treatment in Tobacco-Dependent Adults. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 202(2), e5–e31. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202005-1982ST

- Hughes, J. R., Stead, L. F., Hartmann‐Boyce, J., Cahill, K., & Lancaster, T. (2014). Antidepressants for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014(1), CD000031. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub4

- Hays, J. T., Hurt, R. D., Rigotti, N. A., Niaura, R., Gonzales, D., Durcan, M. J., Sachs, D. P. L., Wolter, T. D., Buist, A. S., Johnston, J. A., & White, J. D. (2001). Sustained-Release Bupropion for Pharmacologic Relapse Prevention after Smoking Cessation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 135(6), 423–433. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-135-6-200109180-00011

- Fiore, M. (n.d.). Treating tobacco use and dependence; 2008 guideline. Retrieved January 17, 2025, from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/6964

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: Treatment overview – UpToDate. (n.d.). Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-in-adults-treatment-overview?search=Attention%20deficit%20hyperactivity%20disorder%20in%20adults%3A%20&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Maneeton, N., Maneeton, B., Srisurapanont, M., & Martin, S. D. (2011). Bupropion for adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 65(7), 611–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02264.x

- Ng, Q. X. (2017). A Systematic Review of the Use of Bupropion for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 27(2), 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2016.0124

- Verbeeck, W., Bekkering, G. E., Van den Noortgate, W., & Kramers, C. (2017). Bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(10), CD009504. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009504.pub2

- Moriyama, T. S., Polanczyk, G. V., Terzi, F. S., Faria, K. M., & Rohde, L. A. (2013). Psychopharmacology and psychotherapy for the treatment of adults with ADHD-a systematic review of available meta-analyses. CNS Spectrums, 18(6), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1017/S109285291300031X

- Montejo, A. L., Prieto, N., de Alarcón, R., Casado-Espada, N., de la Iglesia, J., & Montejo, L. (2019). Management Strategies for Antidepressant-Related Sexual Dysfunction: A Clinical Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(10), 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101640

- Clayton, A. H., Warnock, J. K., Kornstein, S. G., Pinkerton, R., Sheldon-Keller, A., & McGarvey, E. L. (2004). A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion SR as an antidote for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v65n0110

- Walker, P. W., Cole, J. O., Gardner, E. A., Hughes, A. R., Johnston, J. A., Batey, S. R., & Lineberry, C. G. (1993). Improvement in fluoxetine-associated sexual dysfunction in patients switched to bupropion. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 54(12), 459–465.

- Dobkin, R. D., Menza, M., Marin, H., Allen, L. A., Rousso, R., & Leiblum, S. R. (2006). Bupropion improves sexual functioning in depressed minority women: An open-label switch study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 26(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jcp.0000194623.07611.90

- Keramatian, K., Chithra, N. K., & Yatham, L. N. (2023). The CANMAT and ISBD Guidelines for the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: Summary and a 2023 Update of Evidence. Focus, 21(4), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20230009

- Pacchiarotti, I., Bond, D. J., Baldessarini, R. J., Nolen, W. A., Grunze, H., Licht, R. W., Post, R. M., Berk, M., Goodwin, G. M., Sachs, G. S., Tondo, L., Findling, R. L., Youngstrom, E. A., Tohen, M., Undurraga, J., González-Pinto, A., Goldberg, J. F., Yildiz, A., Altshuler, L. L., … Vieta, E. (2013). The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force Report on Antidepressant Use in Bipolar Disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(11), 1249–1262. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185

- Li, D.-J., Tseng, P.-T., Chen, Y.-W., Wu, C.-K., & Lin, P.-Y. (2016). Significant Treatment Effect of Bupropion in Patients With Bipolar Disorder but Similar Phase-Shifting Rate as Other Antidepressants: A Meta-Analysis Following the PRISMA Guidelines. Medicine, 95(13), e3165. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003165

- McIntyre, R. S., Mancini, D. A., McCann, S., Srinivasan, J., Sagman, D., & Kennedy, S. H. (2002). Topiramate versus bupropion SR when added to mood stabilizer therapy for the depressive phase of bipolar disorder: A preliminary single-blind study. Bipolar Disorders, 4(3), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01189.x

- Yanovski, S. Z., & Yanovski, J. A. (2015). Naltrexone-Extended Release plus Bupropion-Extended Release for Treatment of Obesity. JAMA, 313(12), 1213–1214. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.1617

- ContraveFDA. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2025, from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/200063s000lbl.pdf

- Saunders, K. H., Igel, L. I., & Aronne, L. J. (2016). An update on naltrexone/bupropion extended-release in the treatment of obesity. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 17(16), 2235–2242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2016.1244527

- Aubin, H.-J. (2002). Tolerability and Safety of Sustained-Release Bupropion in the Management of Smoking Cessation: Drugs, 62, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200262002-00005

- Foley, K. F., DeSanty, K. P., & Kast, R. E. (2006). Bupropion: Pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 6(9), 1249–1265. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.6.9.1249

- Bupropion: Drug information – UpToDate. (n.d.).

- Trivedi, M. H., Rush, A. J., Carmody, T. J., Donahue, R. M., Bolden-Watson, C., Houser, T. L., & Metz, A. (2001). Do bupropion SR and sertraline differ in their effects on anxiety in depressed patients? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(10), 776–781. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v62n1005

- Westfall, N. C., & Coffey, B. J. (2018). Medication Reconciliation: Making Bupropion Work After a “Bad Experience.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 28(3), 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2018.29147.bjc

- Kelly, K., Posternak, M., & Jonathan, E. A. (2008). Toward achieving optimal response: Understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/kkelly

- Petimar, J., Young, J. G., Yu, H., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Daley, M. F., Heerman, W. J., Janicke, D. M., Jones, W. S., Lewis, K. H., Lin, P.-I. D., Prentice, C., Merriman, J. W., Toh, S., & Block, J. P. (2024). Medication-Induced Weight Change Across Common Antidepressant Treatments. Annals of Internal Medicine, 177(8), 993–1003. https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-2742

- Thase, M. E., Fayyad, R., Cheng, R. J., Guico-Pabia, C. J., Sporn, J., Boucher, M., & Tourian, K. A. (2015). Effects of desvenlafaxine on blood pressure in patients treated for major depressive disorder: A pooled analysis. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 31(4), 809–820. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2015.1020365

- Vanderkooy, J., Ken nedy, S. ney H., & Bagby, R. M. chael. (2002). Antidepressant Side Effects in Depression Patients Treated in a Naturalistic Setting: A Study of Bupropion, Moclobemide, Paroxetine, Sertraline, and Venlafaxine. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47(2), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370204700208

- Demling, J., Beyer, S., & Kornhuber, J. (2010). To sweat or not to sweat? A hypothesis on the effects of venlafaxine and SSRIs. Medical Hypotheses, 74(1), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.07.011

- Ghaleiha, A., Shahidi, K. M., Afzali, S., & Matinnia, N. (2013). Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 17(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

- Grootens, K. P. (2011). Oxybutynin for antidepressant-induced hyperhidrosis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(3), 330–331. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10091348

- Davidson, J. (1989). Seizures and bupropion: A review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 50(7), 256–261.

- Wu, C.-S., Liu, H.-Y., Tsai, H.-J., & Liu, S.-K. (2017). Seizure Risk Associated With Antidepressant Treatment Among Patients With Depressive Disorders: A Population-Based Case-Crossover Study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(9), e1226–e1232. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16m11377

- Omri, M., Ferhi, M., Rauschenbach, C., Ibrahim, A., Oliveira Galvao, M., & Hamm, O. (2024). Understanding De Novo Bupropion-Induced Psychosis and Its Management Strategies: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.73980

- Narayanan, V. (2019). Ocular Adverse Effects of Antidepressants – Need for an Ophthalmic Screening and Follow up Protocol. Ophthalmology Research: An International Journal, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.9734/or/2019/v10i330107

- González‐Urbieta, I., Jafferany, M., & Torales, J. (2021). Bupropion in dermatology: A brief update. Dermatologic Therapy, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14303

- Cartwright, A. M., Shaw, J. T., & Traiger, D. (n.d.). Bupropion-Induced Delayed Hypersensitivity Serum Sickness-Like Reaction. Cureus, 15(3), e36158. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36158

- Evans, E. A., & Sullivan, M. A. (2014). Abuse and misuse of antidepressants. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 5, 107–120. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S37917

- Stassinos, G. L., & Klein-Schwartz, W. (2016). Bupropion “abuse” reported to us poison centers. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(5), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000249

- Kaur, J., Modesto-Lowe, V., & León-Barriera, R. (2024). Do not overlook bupropion misuse. Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 26(2), 54349. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.23lr03685

- Aikoye, S., Basiru, T. O., Nwoye, I., Adereti, I., Asuquo, S., Ezeokoli, A., Hardy, J., & Umudi, O. (2023). A Systematic Review of Abuse or Overprescription of Bupropion in American Prisons and a Synthesis of Case Reports on Bupropion Abuse in American Prison and Non-prison Systems. Cureus, 15(3), e36189. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36189

- Cole, J. A., Modell, J. G., Haight, B. R., Cosmatos, I. S., Stoler, J. M., & Walker, A. M. (2007). Bupropion in pregnancy and the prevalence of congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 16(5), 474–484. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1296

- Turner, E., Jones, M., Vaz, L. R., & Coleman, T. (2019). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis to Assess the Safety of Bupropion and Varenicline in Pregnancy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 21(8), 1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty055

- Alwan, S., Reefhuis, J., Botto, L. D., Rasmussen, S. A., Correa, A., Friedman, J. M., & National Birth Defects Prevention Study. (2010). Maternal use of bupropion and risk for congenital heart defects. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 203(1), 52.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.015

- Louik, C., Kerr, S., & Mitchell, A. A. (2014). First-trimester exposure to bupropion and risk of cardiac malformations. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 23(10), 1066–1075. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3661

- Huybrechts, K. F., Palmsten, K., Avorn, J., Cohen, L. S., Holmes, L. B., Franklin, J. M., Mogun, H., Levin, R., Kowal, M., Setoguchi, S., & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2014). Antidepressant Use in Pregnancy and the Risk of Cardiac Defects. The New England Journal of Medicine, 370(25), 2397–2407. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1312828

- Brumbaugh, J. E., Ball, C. T., Crook, J. E., Stoppel, C. J., Carey, W. A., & Bobo, W. V. (2023). Poor Neonatal Adaptation After Antidepressant Exposure During the Third Trimester in a Geographically Defined Cohort. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 7(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.02.002

- Huybrechts, K. F., Bateman, B. T., Palmsten, K., Desai, R. J., Patorno, E., Gopalakrishnan, C., Levin, R., Mogun, H., & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2015). Antidepressant Use Late in Pregnancy and Risk of Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the Newborn. JAMA, 313(21), 2142–2151. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.5605

- Siu, A. L., & U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2015). Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(8), 622–634. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2023

- Patnode, C. D., Henderson, J. T., Coppola, E. L., Melnikow, J., Durbin, S., & Thomas, R. G. (2021). Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA, 325(3), 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.23541

- Nanovskaya, T. N., Onkcen, C., Fokina, V. M., Feinn, R. S., Clark, S. M., WEST, H., JAIN, S. K., AHMED, M. S., & HANKINS, G. D. V. (2017). Bupropion Sustained-Release for Pregnant Smokers: A Randomized, Placebo Controlled Trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 216(4), 420.e1–420.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.1036

- Haas, J., Kaplan, C., Barenboim, D., Jacob, P., & Benowitz, N. (2004). Bupropion in breast milk: An exposure assessment for potential treatment to prevent post-partum tobacco use. Tobacco Control, 13(1), 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2003.004093

- Chaudron, L. H., & Schoenecker, C. J. (2004). Bupropion and breastfeeding: A case of a possible infant seizure. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(6), 881–882. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v65n0622f

- Neuman, G., Colantonio, D., Delaney, S., Szynkaruk, M., & Ito, S. (2014). Bupropion and Escitalopram During Lactation. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 48(7), 928–931. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028014529548

- Nagler, E. V., Webster, A. C., Vanholder, R., & Zoccali, C. (2012). Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety with recommendations by European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation: Official Publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association – European Renal Association, 27(10), 3736–3745. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfs295

- Sweet, R. A., Pollock, B. G., Kirshner, M., Wright, B., Altieri, L. P., & DeVane, C. L. (1995). Pharmacokinetics of single- and multiple-dose bupropion in elderly patients with depression. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 35(9), 876–884. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04132.x

- Greenblatt, D. J., Harmatz, J. S., & Chow, C. R. (2018). Vortioxetine Disposition in Obesity: Potential Implications for Patient Safety. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 38(3), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000861