In a nutshell

Desvenlafaxine matches venlafaxine’s antidepressant efficacy while offering simpler dosing and minimal drug interactions. Desvenlafaxine lacks venlafaxine’s efficacy for anxiety and pain. Opt for desvenlafaxine when needing more straightforward dosing, or if there are drug interaction concerns. Consider venlafaxine for cases requiring flexible dosing or treatment beyond depression.

- Compared to venlafaxine

- Simplified dosing: 50 mg/day, starting and target dose.

- Favorable tolerability profile: lower discontinuation rates, risk of sexual dysfunction, lower risk of drug-drug interactions [1].

- Less versatile: FDA-approved only for MDD vs. multiple indications for venlafaxine.

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

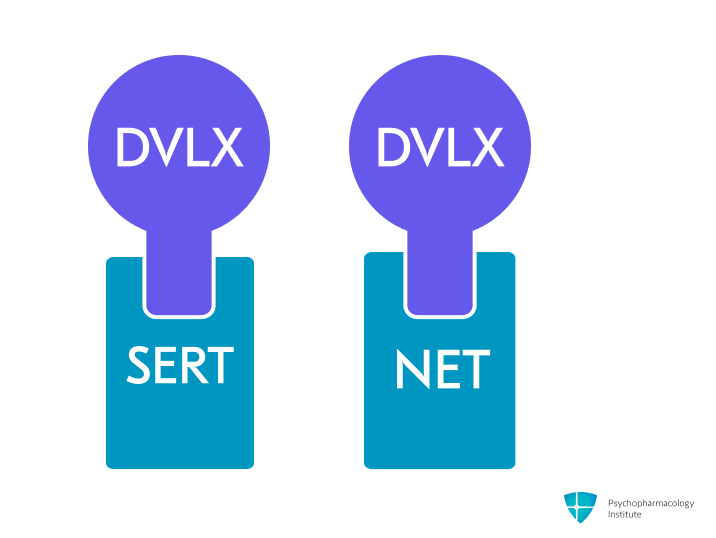

- Potent and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition (SNRI), by blocking SERT and NET.

- Compared to venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine shows more potent noradrenergic effects [2].

- By blocking NET, desvenlafaxine increases prefrontal dopamine levels, suggesting potential benefits for MDD-related cognitive dysfunction.

- Though mechanistically sound, clinical evidence for cognitive improvement remains preliminary [3].

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism

- Primarily metabolized through conjugation.

- Minimal involvement of the CYP450 system.

- Only minor oxidation occurs via CYP3A4.

- CYP2D6 does not significantly metabolize desvenlafaxine.

- No clinically significant interactions with drugs metabolized by CYP enzymes [4].

- A preferred option for:

- Patients at risk of drug-drug interactions.

- Those with genetic polymorphisms affecting CYP2D6 activity [2].

- Drug interactions:

- Contraindicated with MAOIs.

- Use caution with serotonergic agents (SNRIs, SSRIs, TCAs, triptans, buspirone, amphetamines, St. John’s Wort) due to serotonin syndrome risk.

Half-life

- Approximately 11 hours, prolonged in renal failure and hepatic failure.

- A longer half-life than venlafaxine (5 hours) contributes to a lower risk of discontinuation syndrome [5].

Dosage forms

- Extended-release:

- Tablets:

- 25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg.

- Generic, Pristiq.

- Tablets:

- Formulation considerations:

- Only the succinate salt form is currently available in the US market. Khedezla (base form) was discontinued.

- The 25 mg tablet is intended primarily for gradual dose reduction when discontinuing treatment.

- Extended-release tablets should be taken once daily, with or without food.

- Desvenlafaxine ER tablets should not be split, crushed, or chewed, as this will disrupt the extended-release mechanism [4].

Indications

FDA-Approved Indications

Major depressive disorder

- Current guidelines support desvenlafaxine as a first-line MDD treatment [6].

- Desvenlafaxine may be particularly effective in older adults (>65 years) or those with more physical symptoms of depression [6].

- SNRIs have been proposed to be especially effective for treating anhedonia and emotional blunting in MDD. This could be linked to their noradrenergic effect [7].

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 50 mg/day, with or without food.

- For most patients, 50 mg/day.

- Target dose: 50 mg/day

- Maximum recommended dose: 100 mg/day for patients who do not respond after 6 weeks (or 7 days in clinically urgent situations).

- Higher doses (>50 mg) show no added benefit but increased side effects, leading to more discontinuations [8].

Off-Label Uses

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

- SSRIs (escitalopram, paroxetine) and select SNRIs (duloxetine, venlafaxine) are first-line options [9].

- Despite being an SNRI, desvenlafaxine has limited evidence for GAD [10,11].

Social anxiety disorder

- Desvenlafaxine did not differ from placebo in one study, while venlafaxine is a first-line drug for the treatment of social anxiety disorder [9].

Panic disorder

- Desvenlafaxine has minimal evidence: just one retrospective chart review [12].

- SSRIs and venlafaxine are considered to be first-line drugs according to clinical practice guidelines [9].

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against desvenlafaxine for the treatment of PTSD [13].

- The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline recommends paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine [14].

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD)

- Desvenlafaxine lacks specific research, though venlafaxine has shown efficacy [15,16].

- British guidelines favor two SSRIs for PMDD (fluoxetine, sertraline), with evidence supporting continuous over luteal-phase dosing [17,18].

Fibromyalgia

- Desvenlafaxine is not a recommended treatment for fibromyalgia, with guidelines favoring other agents such as duloxetine and pregabalin [19].

Vasomotor symptoms of menopause

- Desvenlafaxine may be an option in patients unable or unwilling to take estrogen. However, it is associated with higher rates of adverse events and discontinuation [20,21].

- Dosing: Starting at 50 mg once daily, with increments up to a target dose of 100 mg daily [22].

Side Effects

Most common side effects

Gastrointestinal

- Nausea

- Less frequent than with venlafaxine [23].

- Reassure your patient that it is not dangerous and usually improves over time.

- Recommend ginger root in some form to alleviate nausea [24].

- Start low, with half the intended dose.

- Other GI effects:

- Dry mouth.

- Constipation.

- Reduced apetite/Anorexia.

Other side effects

- Antidepressant-induced excessive sweating (ADIES)

- Incidence: 10% at 50mg dose [4].

- Dose reduction isn’t usually practical with desvenlafaxine since 50mg is already the standard therapeutic dose.

- Consider switching to an SSRI [25].

- Terazosin and oxybutynin have shown efficacy in reducing ADIES [26,27].

- Sleep and alertness

- Insomnia (9-12%). Less prevalent than with venlafaxine across dosages [28].

- Somnolence (9%) [4].

- Dizziness (10-13%)

- Sexual dysfunction

- Ranking of risk: SSRIs and venlafaxine > tricyclics > other SNRIs [29].

- Desvenlafaxine shows lower sexual dysfunction rates vs SSRIs/venlafaxine, possibly due to its unique pharmacodynamic profile [30].

- Discontinuation syndrome

- Increased incidence at higher dosages, possibly related to noradrenergic effects.

- SNRIs, paroxetine, and mirtazapine have the highest risk among antidepressants [31].

- 25mg dose available for tapering

- Headache

- Nervousness

- Lipid effects

- Clinical trials show minor cholesterol, LDL, and triglyceride elevations, typically not clinically significant at standard doses [28,32].

Severe side effects

- Dose-related hypertension

- Relatively low hypertension rates of 1.9-2.4% across its dosing range [33].

- In comparison, venlafaxine causes hypertension in 10-15% (immediate-release) and 6% (extended-release) of patients [34].

- When normotensive patients develop hypertension on SNRIs, do not immediately discontinue the medication. First, investigate other contributing factors [28].

- Relatively low hypertension rates of 1.9-2.4% across its dosing range [33].

- Hyponatremia

- Ranking of risk [35]:

- MAOIs > SNRIs > SSRIs > TCAs > Mirtazapine

- For hyponatremia-prone patients:

- Mirtazapine should be considered the antidepressant of choice.

- SNRIs should be prescribed more cautiously than SSRIs.

- Higher risk: elderly, especially women on diuretics.

- Monitor sodium in high-risk patients.

- Ranking of risk [35]:

- Serotonin syndrome

- Risk increases with other serotonergic drugs.

- Bleeding risk

- Increased with aspirin, NSAIDs, and anticoagulants [4].

- Monitor if the combination is necessary.

Use in special populations

Pregnancy

- First-trimester safety:

- No increased malformation risk across 3,186 pregnancies [36]

- Maternal health risks:

- SNRIs use in the final month before delivery has been associated with an increase in postpartum hemorrhage risk by up to 2-fold, but residual confounding possible [37,38].

- Hypertensive complications emerge primarily after 20 weeks [39].

- Neonatal effects:

- PPHN risk elevated 1.83-fold, requiring 1,000 exposures for one case [40].

- Transient complications like poor neonatal adaptation reported with third trimester exposure [41].

Breastfeeding

- Generally safe – low infant exposure (6.8% maternal dose) [42].

- May reduce breastfeeding initiation rates [43].

- Rare reports of elevated prolactin/galactorrhea [44].

Hepatic impairment

- Desvenlafaxine does not require dose adjustments for hepatic impairment.

- Maximum dose 100 mg/day in moderate/severe impairment (Child-Pugh 7-15).

- Its metabolism occurs independently of liver function.

- This differs from venlafaxine and duloxetine, which have hepatic dosing restrictions [45].

Renal impairment

- Mild (CLcr 60–89 mL/min):

- No adjustment needed.

- Moderate (CLcr 30–59 mL/min):

- Maximum 50 mg/day.

- Severe (CLcr <30 mL/min) or ESRD: Maximum 25 mg/day or 50 mg every other day.

- Age-related renal decline alone doesn’t require adjustment [45].

Elderly

- No dose adjustment is routinely needed.

Brand names

- US: Pristiq

- Canada: Pristiq

- Other countries/regions: Alfaxin, Andes, Bedremine, Butran, Calmax, Dalilah, Datizine, Davlex, Deller, D-fax, D-flaxene, Disin, Drosix, Dt xt, Dvpex, Elifor, Elifore, Enzude, Exlov, Exsira, Fapris, Faxidepres, Hapytab, Imense, Indefa, Irsyn, Ixium, Lafaxine, Lafaxtor, Lornox, Mdd, Mistic, Neo moor, Nevola, Newven, Nexvenla, Oraxine, Prenexa, Prestiq, Prismaven, Pristimood, Pristiq, Qrist, Resvelare, Rielafix, Rytmise, Scotiq, Seristiq, Sigven, Siclot, Styma, Vaxoban, Velasar, Veldex, Vellana, Vendep, Vendexla, Venadex, Vencontrol, Venlatrope, Venlife, Venlite, Venpower, Vensol, Ventab, Venz, Zodel, Zyven

References

- Sampogna, G., Caraci, F., Carmassi, C., Dell’Osso, B., Ferrari, S., Martinotti, G., Sani, G., Serafini, G., Signorelli, M. S., & Fiorillo, A. (2023). Efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine in the real-world treatment of patients with major depression: A narrative review and an expert opinion paper. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 24(14), 1511–1525. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2023.2237410

- Colvard, M. D. (2014). Key differences between Venlafaxine XR and Desvenlafaxine: An analysis of pharmacokinetic and clinical data. Mental Health Clinician, 4(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.n186977

- Blumberg, M. J., Vaccarino, S. R., & McInerney, S. J. (2020). Procognitive Effects of Antidepressants and Other Therapeutic Agents in Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 81(4). https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.19r13200

- Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (2023). PRISTIQ (desvenlafaxine) Extended-Release Tablets Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/021992s051lbl.pdf

- Puzantian, T., & Carlat, D. (2024). Medication Fact Book for Psychiatric Practice 7th Edition.

- Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Adams, C., Bahji, A., Beaulieu, S., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Blumberger, D. M., Brietzke, E., Chakrabarty, T., Do, A., Frey, B. N., Giacobbe, P., Gratzer, D., Grigoriadis, S., Habert, J., Ishrat Husain, M., Ismail, Z., McGirr, A., … Milev, R. V. (2024). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023 : Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can. J. Psychiatry, 69(9), 641–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437241245384

- Allam, M. A. (2023). Is the most really the best: A review for the most selective SSRI concept three decades later. European Psychiatry, 66(S1), S417–S417. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.899

- Clayton, A. H., Tourian, K. A., Focht, K., Hwang, E., Cheng, R.-F. J., & Thase, M. E. (2015). Desvenlafaxine 50 and 100 mg/d versus placebo for the treatment of major depressive disorder: A phase 4, randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry, 76(5), 562–569. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08978

- Bandelow, B., Allgulander, C., Baldwin, D. S., Costa, D. L. da C., Denys, D., Dilbaz, N., Domschke, K., Eriksson, E., Fineberg, N. A., Hättenschwiler, J., Hollander, E., Kaiya, H., Karavaeva, T., Kasper, S., Katzman, M., Kim, Y.-K., Inoue, T., Lim, L., Masdrakis, V., … Zohar, J. (2023). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders – Version 3. Part I: Anxiety disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry, 24(2), 79–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2022.2086295

- Kornstein, S. G., Guico-Pabia, C. J., & Fayyad, R. S. (2014). The effect of desvenlafaxine 50 mg/day on a subpopulation of anxious/depressed patients: A pooled analysis of seven randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Hum. Psychopharmacol., 29(5), 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2427

- Tourian, K. A., Jiang, Q., & Ninan, P. T. (2010). Analysis of the effect of desvenlafaxine on anxiety symptoms associated with major depressive disorder: Pooled data from 9 short-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. CNS Spectr., 15(3), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852900027450

- Min Lee, S., & Kyung Park, J. (2022). Desvenlafaxine extended-release in panic disorder: A retrospective chart review. Alpha Psychiatry, 23(3), 142–143. https://doi.org/10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2022.21703

- Schnurr, P. P., Hamblen, J. L., Wolf, J., Coller, R., Collie, C., Fuller, M. A., Holtzheimer, P. E., Kelly, U., Lang, A. J., McGraw, K., Morganstein, J. C., Norman, S. B., Papke, K., Petrakis, I., Riggs, D., Sall, J. A., Shiner, B., Wiechers, I., & Kelber, M. S. (2024). The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder: Synopsis of the 2023 U.s. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.s. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med., 177(3), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-2757

- Williams, T., Phillips, N. J., Stein, D. J., & Ipser, J. C. (2022). Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., 3, CD002795. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002795.pub3

- Hsiao, M.-C., & Liu, C.-Y. (2003). Effective open-label treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with venlafaxine. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 57(3), 317–321. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01123.x

- Cohen, L. S., Soares, C. N., Lyster, A., Cassano, P., Brandes, M., & Leblanc, G. A. (2004). Efficacy and Tolerability of Premenstrual Use of Venlafaxine (Flexible Dose) in the Treatment of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(5), 540–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jcp.0000138767.53976.10

- Green, L. J., Obrien, P., Panay, N., & Craig, M. (2017). Management of premenstrual syndrome. BJOG, 124, e73–e105.

- Jespersen, C., Lauritsen, M. P., Frokjaer, V. G., & Schroll, J. B. (2024). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., 8(8), CD001396. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub4

- Kia, S., & Choy, E. (2017). Update on treatment guideline in fibromyalgia syndrome with focus on pharmacology. Biomedicines, 5(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines5020020

- Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. (2015). Menopause, 22(11), 1155-72; quiz 1173-4. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000546

- Berhan, Y., & Berhan, A. (2014). Is desvenlafaxine effective and safe in the treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms? A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized double-blind controlled studies. Ethiop. J. Health Sci., 24(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v24i3.4

- Sun, Z., Hao, Y., & Zhang, M. (2013). Efficacy and safety of desvenlafaxine treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest., 75(4), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348564

- Oliva, V., Lippi, M., Paci, R., Del Fabro, L., Delvecchio, G., Brambilla, P., De Ronchi, D., Fanelli, G., & Serretti, A. (2021). Gastrointestinal side effects associated with antidepressant treatments in patients with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 109, 110266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110266

- Kelly, K., Posternak, M., & Jonathan, E. A. (2008). Toward achieving optimal response: Understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/kkelly

- Demling, J., Beyer, S., & Kornhuber, J. (2010). To sweat or not to sweat? A hypothesis on the effects of venlafaxine and SSRIs. Medical Hypotheses, 74(1), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.07.011

- Ghaleiha, A., Shahidi, K. M., Afzali, S., & Matinnia, N. (2013). Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 17(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

- Grootens, K. P. (2011). Oxybutynin for antidepressant-induced hyperhidrosis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(3), 330–331. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10091348

- Goldberg, J. F., & Ernst, C. L. (2018). Managing the Side Effects of Psychotropic Medications (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://www.perlego.com/book/4276007/managing-the-side-effects-of-psychotropic-medications-pdf?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&campaignid=19798557528&adgroupid=167850339806&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiAxKy5BhBbEiwAYiW–0Vjffl7eUvQrh8fYFOhOKx6pFHCz5G55nWtyGe5ei5zL_AvfwKTvhoCgasQAvD_BwE

- Winter, J., Curtis, K., Hu, B., & Clayton, A. H. (2022). Sexual dysfunction with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatments: Impact, assessment, and management. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 21(7), 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2022.2049753

- Montejo, A. L., Becker, J., Bueno, G., Fernández-Ovejero, R., Gallego, M. T., González, N., Juanes, A., Montejo, L., Pérez-Urdániz, A., Prieto, N., & Villegas, J. L. (2019). Frequency of Sexual Dysfunction in Patients Treated with Desvenlafaxine: A Prospective Naturalistic Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(5), 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050719

- Horowitz, M. A., Framer, A., Hengartner, M. P., Sørensen, A., & Taylor, D. (2023). Estimating Risk of Antidepressant Withdrawal from a Review of Published Data. CNS Drugs, 37(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y

- 32. Lieberman, D. Z., & Massey, S. H. (2010). Desvenlafaxine in major depressive disorder: An evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Core Evidence, 4, 67. https://doi.org/10.2147/ce.s5998

- Thase, M. E., Fayyad, R., Cheng, R. J., Guico-Pabia, C. J., Sporn, J., Boucher, M., & Tourian, K. A. (2015). Effects of desvenlafaxine on blood pressure in patients treated for major depressive disorder: A pooled analysis. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 31(4), 809–820. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2015.1020365

- Calvi, A., Fischetti, I., Verzicco, I., Belvederi Murri, M., Zanetidou, S., Volpi, R., Coghi, P., Tedeschi, S., Amore, M., & Cabassi, A. (2021). Antidepressant Drugs Effects on Blood Pressure. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 8, 704281. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.704281

- Gheysens, T., Van Den Eede, F., & De Picker, L. (2024). The risk of antidepressant-induced hyponatremia: A meta-analysis of antidepressant classes and compounds. European Psychiatry, 67(1), e20. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2024.11

- Lassen, D., Ennis, Z. N., & Damkier, P. (2016). First-Trimester Pregnancy Exposure to Venlafaxine or Duloxetine and Risk of Major Congenital Malformations: A Systematic Review. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 118(1), 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.12497

- Hanley, G. E., Smolina, K., Mintzes, B., Oberlander, T. F., & Morgan, S. G. (2016). Postpartum Hemorrhage and Use of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants in Pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(3), 553. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001200

- Palmsten, K., Huybrechts, K. F., Michels, K. B., Williams, P. L., Mogun, H., Setoguchi, S., & Hernández-Díaz, S. (2013). Antidepressant Use and Risk for Preeclampsia. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 24(5), 682–691. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31829e0aaa

- Newport, D. J., Hostetter, A. L., Juul, S. H., Porterfield, M. S., Knight, B. T., & Stowe, Z. N. (2016). Prenatal psychostimulant and antidepressant exposure and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(11), 1538–1545. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m10506

- Masarwa, R., Bar-Oz, B., Gorelik, E., Reif, S., Perlman, A., & Matok, I. (2019). Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and network meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 220(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.030

- Kieviet, N., Hoppenbrouwers, C., Dolman, K. M., Berkhof, J., Wennink, H., & Honig, A. (2015). Risk factors for poor neonatal adaptation after exposure to antidepressants in utero. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992), 104(4), 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12921

- Desvenlafaxine. (2006). In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501592/

- Grzeskowiak, L. E., Saha, M. R., Nordeng, H., Ystrom, E., & Amir, L. H. (2022). Perinatal antidepressant use and breastfeeding outcomes: Findings from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 101(3), 344. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14324

- Tourian, K. A., Pitrosky, B., Padmanabhan, S. K., & Rosas, G. R. (2011). A 10-Month, Open-Label Evaluation of Desvenlafaxine in Outpatients With Major Depressive Disorder. The Primary Care Companion to CNS Disorders, 13(2), PCC.10m00977. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.10m00977blu

- 4Nichols, A. I., Tourian, K. A., Tse, S. Y., & Paul, J. (2010). Desvenlafaxine for major depressive disorder: Incremental clinical benefits from a second-generation serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 6(12), 1565–1574. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425255.2010.535810