In a nutshell

- Dose-dependent effects:

- Venlafaxine’s efficacy increases with higher doses, but this comes at the cost of decreased acceptability and tolerability1.

- Higher doses are associated with elevated blood pressure.

- Efficacy for anhedonia and fatigue:

- Venlafaxine may help patients with anhedonia and fatigue, likely due to its effects on norepinephrine and dopamine pathways2.

- High risk of discontinuation syndrome:

- Venlafaxine has a higher risk of discontinuation syndrome than other antidepressants3.

Pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action

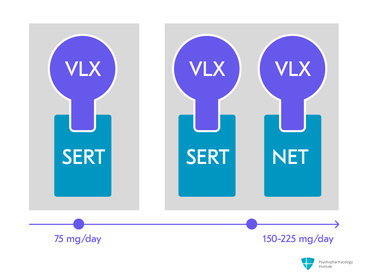

- Venlafaxine’s mechanism of action appears to be dose-dependent:

- At lower doses (37.5-75 mg/day): serotonin reuptake inhibition.

- At moderate doses (150−225 mg/day): dual mechanism agent affecting serotonin and norepinephrine4,5.

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism

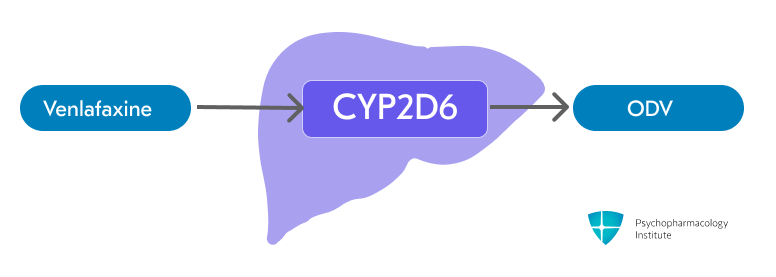

Venlaxafine is metabolized to O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV)

- Venlafaxine is primarily metabolized to its active metabolite, O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV), via CYP2D6.

- CYP3A4 is involved in the metabolism of venlafaxine, though to a lesser extent than CYP2D6.6

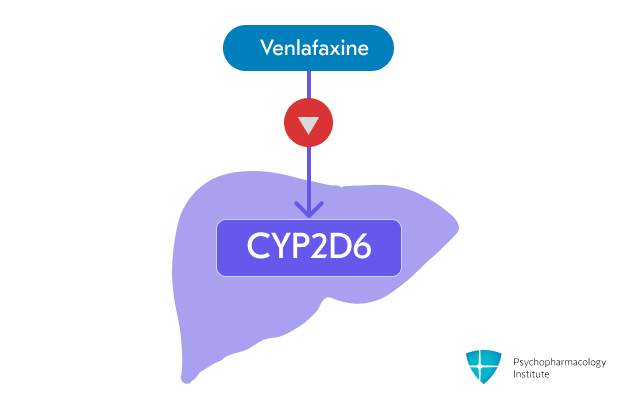

Venlafaxine is a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6

- Venlafaxine is a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6

- It may increase the concentrations of CYP2D6 substrates

- Caution when used with other drugs metabolized by CYP2D6

- Drug interactions:

- Contraindicated with MAOIs

- CYP3A4 inhibitors may increase venlafaxine and ODV levels

Half-life

- Venlafaxine and its active metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV) have different half-lives.

- Venlafaxine: 5 hours

- O-desmethylvenlafaxine (ODV): 11 hours

Dosage forms

- Immediate-release:

- Tablets:

- 25 mg, 37.5 mg, 50 mg, 75 mg, 100 mg

- Generic

- Tablets:

- Extended-release:

- Capsules:

- 37.5 mg, 75 mg, 150 mg

- Generic, Effexor XR

- Tablets:

- 37.5 mg, 75 mg, 150 mg, 225 mg

- Generic

- Tablets (besylate salt):

- 112.5 mg

- Generic

- Capsules:

Indications

FDA-Approved Indications

Major depressive disorder

- Guidelines recommend venlafaxine-XR as a first-line pharmacotherapy for major depression7.

- Dose-dependent action:

- At lower doses (37.5 –75 mg/day), venlafaxine can be considered to act as an SSRI primarily.

- At higher doses (150-225 mg/day), its noradrenergic effects can help treat the anhedonia/fatigue symptom cluster.

- Venlafaxine is an option to switch to if patients do not adequately respond to the initial antidepressant prescribed8.

- Dosing

- Starting dose: 37.5 –75 mg/day.

- For most patients, 75 mg/day.

- Target dose: 75 mg/day

- Increments: no faster than 75 mg every 4 days.

- Maximum recommended dose: 225 mg/day

- Formulation considerations:

- XR capsules and tablets: taken once daily, with food.

- IR tablets can be divided into 2-3 daily doses.

- If XR formulations are broken, the extended-release properties will be altered.

Generalized anxiety disorder

- SSRIs and SNRIs are first-line pharmacotherapies for GAD9.

- Dosing:

- Starting dose:

- For most patients, 75 mg/day

- For some patients, 37.5 mg/day

- Target dose: 75 mg/day

- Increments: no faster than 75 mg every 4 days.

- Maximum recommended dose: 225 mg/day

- Starting dose:

Social anxiety disorder

- Venlafaxine is a first-line drug for the treatment of SAD .

- Venlafaxine and paroxetine are similarly effective, according to a comparison trial10.

- Similar discontinuation rates, but paroxetine had better tolerability, with fewer adverse events requiring dose adjustment.

- Dosing:

- Starting dose: 75 mg/day

- Target dose: 75 mg/day

- Maximum dose: 75 mg/day (no benefit at higher doses)

Panic disorder

- Venlafaxine and SSRIs are first-line pharmacotherapies for panic disorder .

- Dosing

- Starting dose: 37.5 mg/day for 7 days

- Target dose: 75 mg/day

- Maximum dose: 225 mg/day

Off-label uses

PTSD

- When pharmacotherapy is needed, guidelines recommend starting with SSRIs such as sertraline or citalopram11.

- SNRIs such as venlafaxine are considered a reasonable first-line option12.

PMDD

- Venlafaxine has shown efficacy for the treatment of PMDD:

- as a continuous dosing strategy (open-label trial)13

- as luteal phase dosing strategy14

Side Effects

Most common side effects

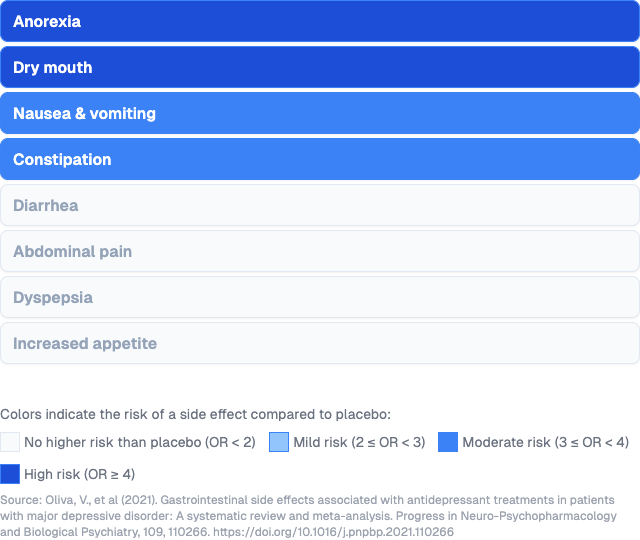

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal side effects

- Anorexia

- Dry mouth

- Nausea

- Reassure your patient that it is not dangerous and usually improves over time.

- Recommend ginger root in some form to alleviate nausea15.

- Start low, with half the intended dose

- Constipation

Other side effects

- Discontinuation syndrome

- Increased incidence at higher dosages, possibly related to noradrenergic effects.

- SNRIs, paroxetine, and mirtazapine have the highest risk among antidepressants.

- Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction

- Ranking of risk: SSRIs and venlafaxine > tricyclics > other SNRIs16.

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Nervousness

- Sleep alterations

- Decrease in REM sleep17.

- Somnolence

- Insomnia

- Sweating

- Dose-related side effect

- If antidepressant dose reduction is clinically feasible, it should be tried18.

Serious side effects

- Dose-related hypertension

- The extended-release formulation has a lower risk of diastolic hypertension19.

- Immediate-release: 10-15% of patients.

- Extended-release: almost 6% of patients.

- Chronic venlafaxine treatment can facilitate the occurrence of hypertensive crises in normotensive patients.

- The extended-release formulation has a lower risk of diastolic hypertension19.

- Hyponatremia

- Ranking of risk:

- MAOIs > SNRIs > SSRIs > TCAs > Mirtazapine20

- For hyponatremia-prone patients:

- Mirtazapine should be considered the antidepressant of choice.

- SNRIs should be prescribed more cautiously than SSRIs

- Ranking of risk:

Use in special populations

Breastfeeding

- Infants’ exposure through breastmilk21

- Infants receive venlafaxine.

- Side effects in breastfed infants have rarely been reported.

- Breastfed infants should be monitored for:

- Excessive sedation

- Adequate weight gain

- A safety scoring system finds venlafaxine use to be possible during breastfeeding22.

- However, some experts do not recommend venlafaxine during nursing23.

Hepatic impairment

- Mild (Child-Pugh Class A, score 5-6)

- Reduce total daily dose by 50%

- Moderate (Child-Pugh Class B, score 7-8)

- Reduce total daily dose by 50%

- Severe (Child-Pugh Class C, score 10-15) or cirrhosis

- Reduce the total daily dose by 50% or more

Renal impairment

- Mild (CLcr 60–89 mL/min)

- Reduce total daily dose by 25-50%

- Moderate (CLcr 30–59 mL/min)

- Reduce total daily dose by 25-50%

- Severe (CLcr <30 mL/min) or undergoing hemodialysis

- Reduce the total daily dose by 50% or more

Elderly

No dose adjustment is needed.

Brand names

- US: Effexor XR

- Canada: Effexor XR

- Other countries/regions: Alventa, Arafaxina, Argofan, Conervin, Deprevix, Dislaven, Dobupal, Duofaxin, Eduxon, Efectin, Efexor, Efevel, Elafax, Elify, Faxine, Faxipaw, Faxiprol, Flavix, Ganavax, Idixor, Jarvis, Lafaxin, Lanvexin, Laroxin, Maxibral, Melocin, Niztec, Norafexine, Norezor, Norpilen, Politid, Pracet, Pramina, Psiseven, Quilarex, Senexon, Serosmine, Sesaren, Sunvex, Tifaxin, Trevilor, Vandral, Vaxor, Velafax, Velaxin, Velostad, Velpine, Vendep, Venexor, Veniba, Veniz, Venlalic, Venxin, Venxor, Viepax, Vilfax, Voxafen, Voxatin, Zacalen, Zarelis, Zaxine

References

- Rush, A., Trivedi, M., Wisniewski, S., Nierenberg, A., Stewart, J., Warden, D., Niederehe, G., Thase, M., Lavori, P., Lebowitz, B., McGrath, P., Rosenbaum, J., Sackeim, H., Kupfer, D., Luther, J., & Fava, M. (2006). Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 354, 1231–1242

- Murawiec, S., & Krzystanek, M. (2021). Symptom Cluster-Matching Antidepressant Treatment: A Case Series Pilot Study. Pharmaceuticals, 14(6), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060526

- Horowitz, M. A., Framer, A., Hengartner, M. P., Sørensen, A., & Taylor, D. (2023). Estimating Risk of Antidepressant Withdrawal from a Review of Published Data. CNS Drugs, 37(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y

- Harvey, A. T., Rudolph, R. L., & Preskorn, S. H. (2000). Evidence of the Dual Mechanisms of Action of Venlafaxine. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(5), 503. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.503

- Fagiolini, A., Cardoner, N., Pirildar, S., Ittsakul, P., Ng, B., Duailibi, K., & El Hindy, N. (2023). Moving from serotonin to serotonin-norepinephrine enhancement with increasing venlafaxine dose: Clinical implications and strategies for a successful outcome in major depressive disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 24(15), 1715–1723. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2023.2242264

- Wyeth Pharmaceuticals LLC, a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc. (2022). EFFEXOR XR- venlafaxine hydrochloride capsule, extended release: Prescribing information. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=53c3e7ac-1852-4d70-d2b6-4fca819acf26

- Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Adams, C., Bahji, A., Beaulieu, S., Bhat, V., Blier, P., Blumberger, D. M., Brietzke, E., Chakrabarty, T., et al. (2024). Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2023 update on clinical guidelines for management of major depressive disorder in adults. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 69(9), 641–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437241245384

- The Management of Major Depressive Disorder Work Group. (2022). Management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (2022). Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/

- Bandelow, B., Allgulander, C., Baldwin, D. S., Costa, D. L. D. C., Denys, D., Dilbaz, N., Domschke, K., Eriksson, E., Fineberg, N. A., Hättenschwiler, J., Hollander, E., Kaiya, H., Karavaeva, T., Kasper, S., Katzman, M., Kim, Y.-K., Inoue, T., Lim, L., Masdrakis, V., … Zohar, J. (2023). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders – Version 3. Part I: Anxiety disorders. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 24(2), 79–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2022.2086295

- Liebowitz, M. R., Gelenberg, A. J., & Munjack, D. (2005). Venlafaxine extended release vs placebo and paroxetine in social anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(2), 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.190

- Stein, M. B. (2024). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: Treatment overview. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-in-adults-treatment-overview

- Bandelow, B., Allgulander, C., Baldwin, D. S., Costa, D. L. da C., Denys, D., Dilbaz, N., & Zohar, J. (2022). World federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders – version 3. Part II: OCD and PTSD. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 24(2), 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2022.2086296

- Hsiao, M.-C., & Liu, C.-Y. (2003). Effective open-label treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with venlafaxine. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 57(3), 317–321. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01123.x

- Cohen, L. S., Soares, C. N., Lyster, A., Cassano, P., Brandes, M., & Leblanc, G. A. (2004). Efficacy and Tolerability of Premenstrual Use of Venlafaxine (Flexible Dose) in the Treatment of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(5), 540–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jcp.0000138767.53976.10

- Kelly, K., Posternak, M., & Jonathan, E. A. (2008). Toward achieving optimal response: Understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/kkelly

- Winter, J., Curtis, K., Hu, B., & Clayton, A. H. (2022). Sexual dysfunction with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatments: Impact, assessment, and management. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 21(7), 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2022.2049753

- Goldberg, J. F., & Ernst, C. L. (2022). Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing

- Thompson, S., Compton, L., Chen, J.-L., & Fang, M.-L. (2021). Pharmacologic treatment of antidepressant-induced excessive sweating: A systematic review. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 48, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.15761/0101-60830000000279

- Calvi, A., Fischetti, I., Verzicco, I., Belvederi Murri, M., Zanetidou, S., Volpi, R., Coghi, P., Tedeschi, S., Amore, M., & Cabassi, A. (2021). Antidepressant Drugs Effects on Blood Pressure. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 8, 704281. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.704281

- Gheysens, T., Van Den Eede, F., & De Picker, L. (2024). The risk of antidepressant-induced hyponatremia: A meta-analysis of antidepressant classes and compounds. European Psychiatry, 67(1), e20. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2024.11

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). (2006). Venlafaxine. In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501192/

- Uguz, F. (2021). A New Safety Scoring System for the Use of Psychotropic Drugs During Lactation. American Journal of Therapeutics, 28(1), e118–e126. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0000000000000909

- Larsen, E. R., Damkier, P., Pedersen, L. H., Fenger-Gron, J., Mikkelsen, R. L., Nielsen, R. E., Linde, V. J., Knudsen, H. E. D., Skaarup, L., & Videbech, P. (2015). Use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 132(S445), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12479