Slides and Transcript

Slide 1 of 21

So, welcome back. We're going to talk a little bit more about the problem of treatment resistance, which is partly a consequence of a treatment model that has come to neglect the psychosocial aspect of care in pharmacotherapy. And it is, I think, a significant problem.

Slide 2 of 21

If you look at references in the psychiatric literature to treatment resistance, you see an interesting phenomenon where just as the psychodynamic model was starting to drop out, the number of references in our literature to treatment-resistant psychiatric conditions really began to increase at an exponential rate.

References:

- Howes, O. D., Thase, M. E., & Pillinger, T. (2022). Treatment resistance in psychiatry: state of the art and new directions. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 58–72. 2

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 3 of 21

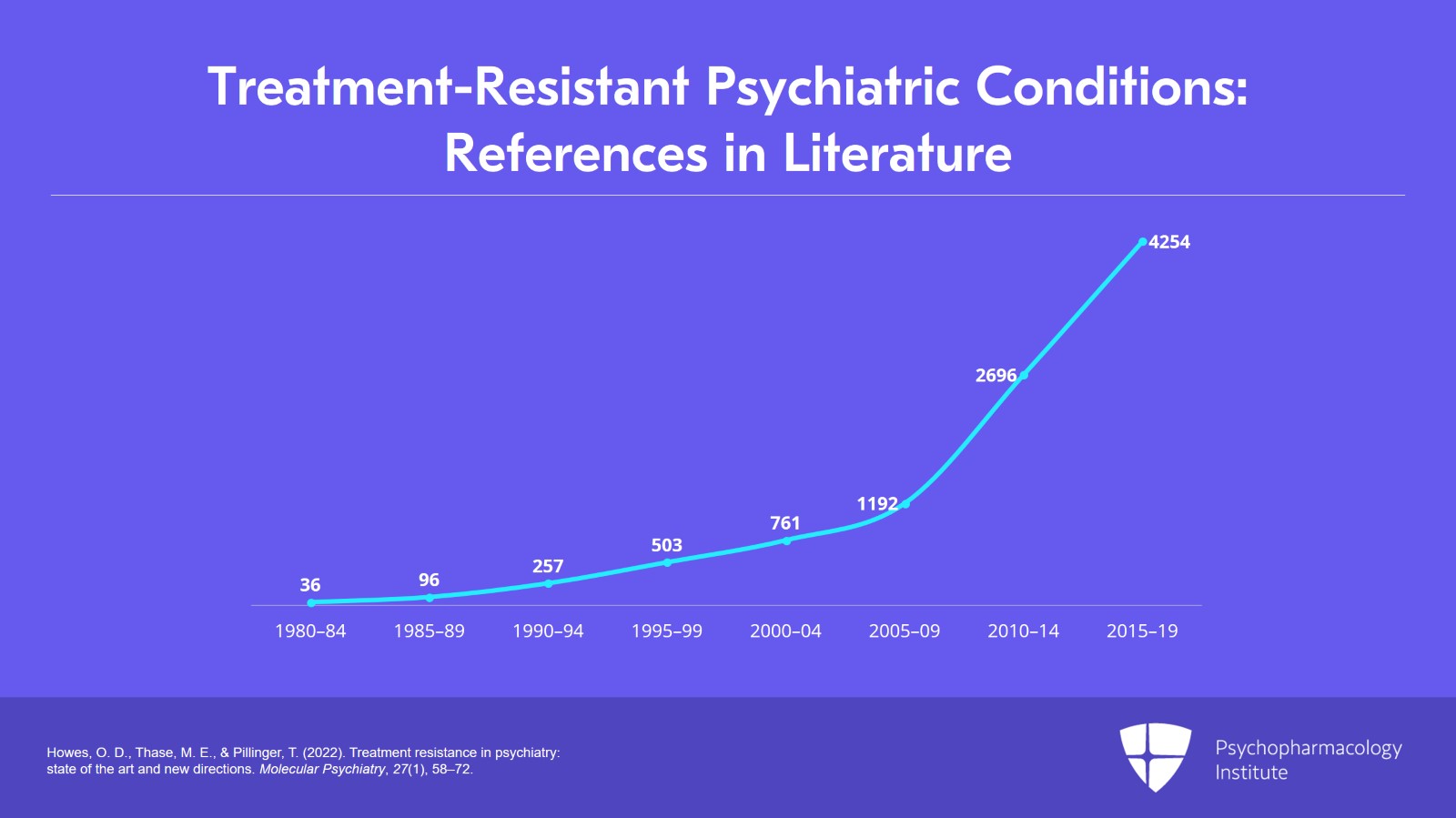

So, in the five-year period from 1980 to 1984 there were 36 references in our literature to treatment-resistant psychiatric conditions. In the next five years, there were 96 references; in the next five years, 257; and five years after that, 503; five years after that, 761; and in 2005 to 2009, 1192; 2010 to 2014, 2696; and in the most recent five-year period, 2015 to 2019, there were 4254 references, so a substantial increase over the last 25 years. That's a 9000% increase. Meanwhile, if you look at just the number of publications, that also increased by about two-fold. So, most of that is really reflecting the recognition in our field that treatment resistance is a significant problem in psychiatry.

References:

- Howes, O. D., Thase, M. E., & Pillinger, T. (2022). Treatment resistance in psychiatry: state of the art and new directions. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 58–72.

Slide 4 of 21

And I think you probably all know this from your practices, because this is who we treat. Patients who are highly treatment responsive get treated by their primary care doctors. They never get to see us. By the time patients get to see us, they have usually failed multiple medications already and primary care doctors are feeling like they need the help of a psychiatrist to find treatments that work.

References:

- Butler, D. J., Fons, D., Fisher, T., Sanders, J., Bodenhamer, S., Owen, J. R., & Gunderson, M. (2018). A review of the benefits and limitations of a primary care-embedded psychiatric consultation service in a medically underserved setting. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 53(5-6), 415–426.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 5 of 21

And this is reflected also on a larger scale, certainly. Thomas Insel, the former director of the NIMH, at the end of his tenure recognized this problem when he said: "I spent 13 years at the NIMH really pushing on the neuroscience and genetics of mental disorders and when I look back on that, I realized that while I think we succeeded at getting lots of really cool papers published by cool scientists at fairly large costs, I think about 20 billion, I don't think we moved the needle in reducing suicide, reducing hospitalizations, improving recovery for the tens of millions of psychiatric patients.”

References:

- Insel, T. (2022). Healing: Our path from mental illness to mental health. Penguin.

- Rogers, A. (2017, May 11). Star neuroscientist Tom Insel leaves the Google-spawned verily for … a startup?. WIRED.

Slide 6 of 21

And one argument I will be making over and over and over again is that there are many things we can do in the moment, in the context of the doctor-patient relationship, that actually help our patients to have better responses to medications and may help them move from non-response to response or even to recovery.

References:

- Kaba, R., & Sooriakumaran, P. (2007). The evolution of the doctor-patient relationship. International Journal of Surgery, 5(1), 57-65.

- Morgan, M. (2008). The doctor-patient relationship. Sociology as applied to medicine. Edinburgh: Saunders Elsevier.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 7 of 21

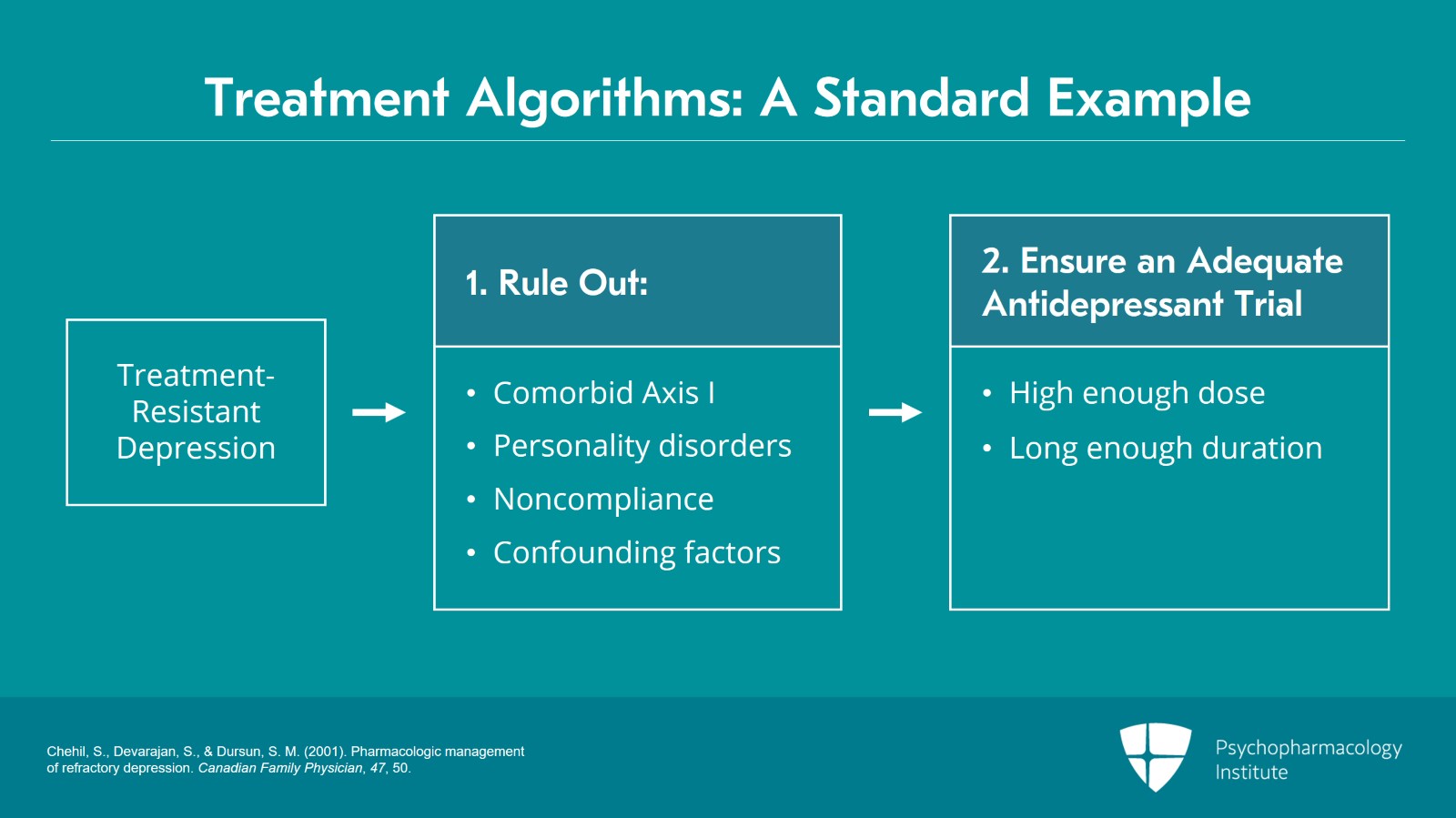

Now, if we look at where we're coming from in terms of treatment algorithms, I've chosen an algorithm for treatment-resistant depression where first you consider and rule out comorbid Axis I or personality disorders, or noncompliance, or complicating and confounding factors. And if those things are absent you want to ensure that there's an adequate trial of the antidepressant, so, high enough dose for a long enough duration before you decide it's not effective.

References:

- Chehil, S., Devarajan, S., & Dursun, S. M. (2001). Pharmacologic management of refractory depression. Canadian Family Physician, 47, 50.

Slide 8 of 21

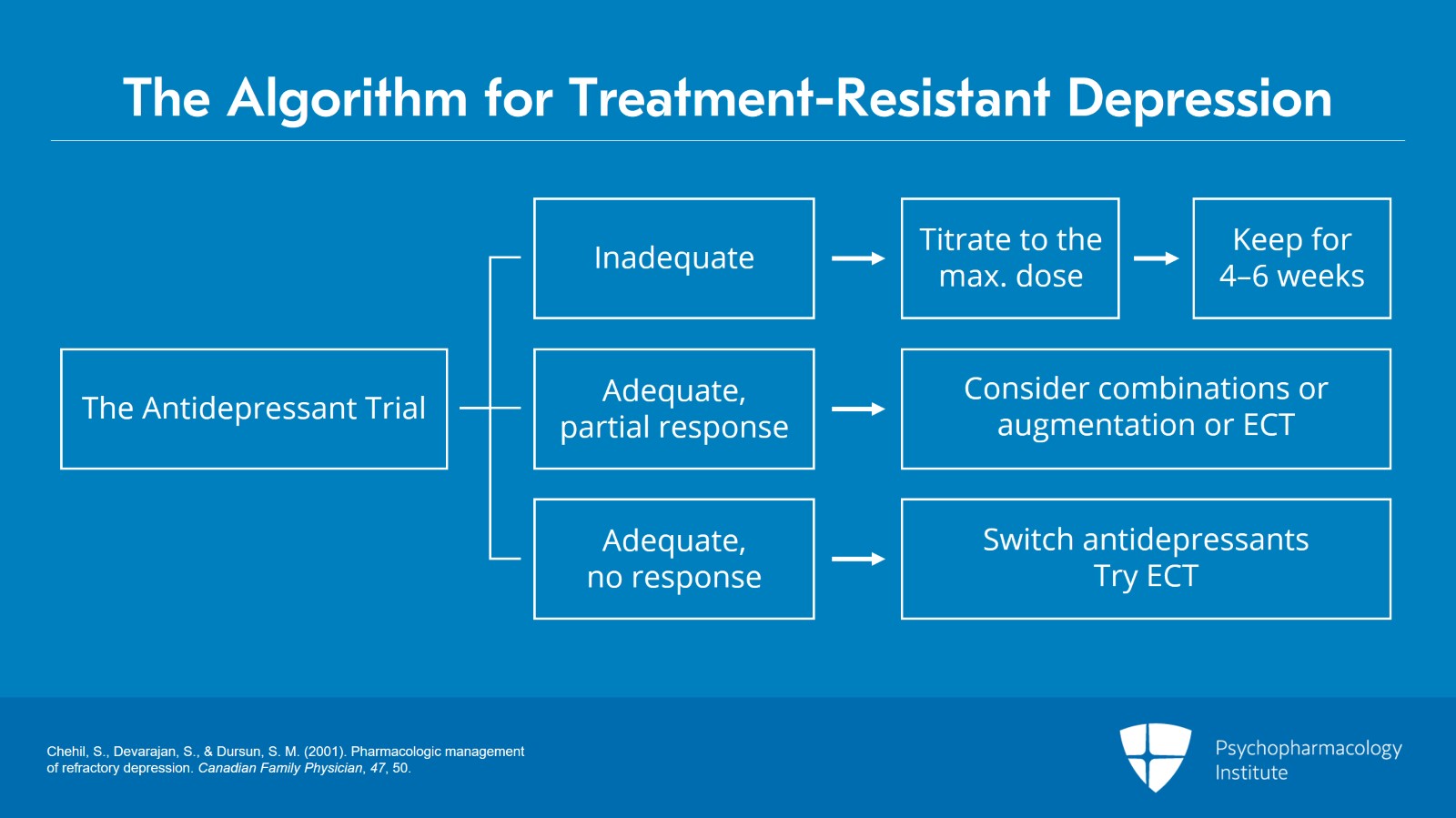

If you have an inadequate trial, you certainly want to titrate to the max dose and make sure the patient is on it for at least four to six weeks. If the patient has had adequate trials with a partial response, you might consider a combination of antidepressants, or augmentation, or maybe ECT. If there's no response at all, you'll switch antidepressants, try ECT. If none of that works, certainly you're beginning to consider whether you have the wrong diagnosis. Maybe this is a bipolar depression, or those kinds of things.

References:

- Chehil, S., Devarajan, S., & Dursun, S. M. (2001). Pharmacologic management of refractory depression. Canadian Family Physician, 47, 50.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 9 of 21

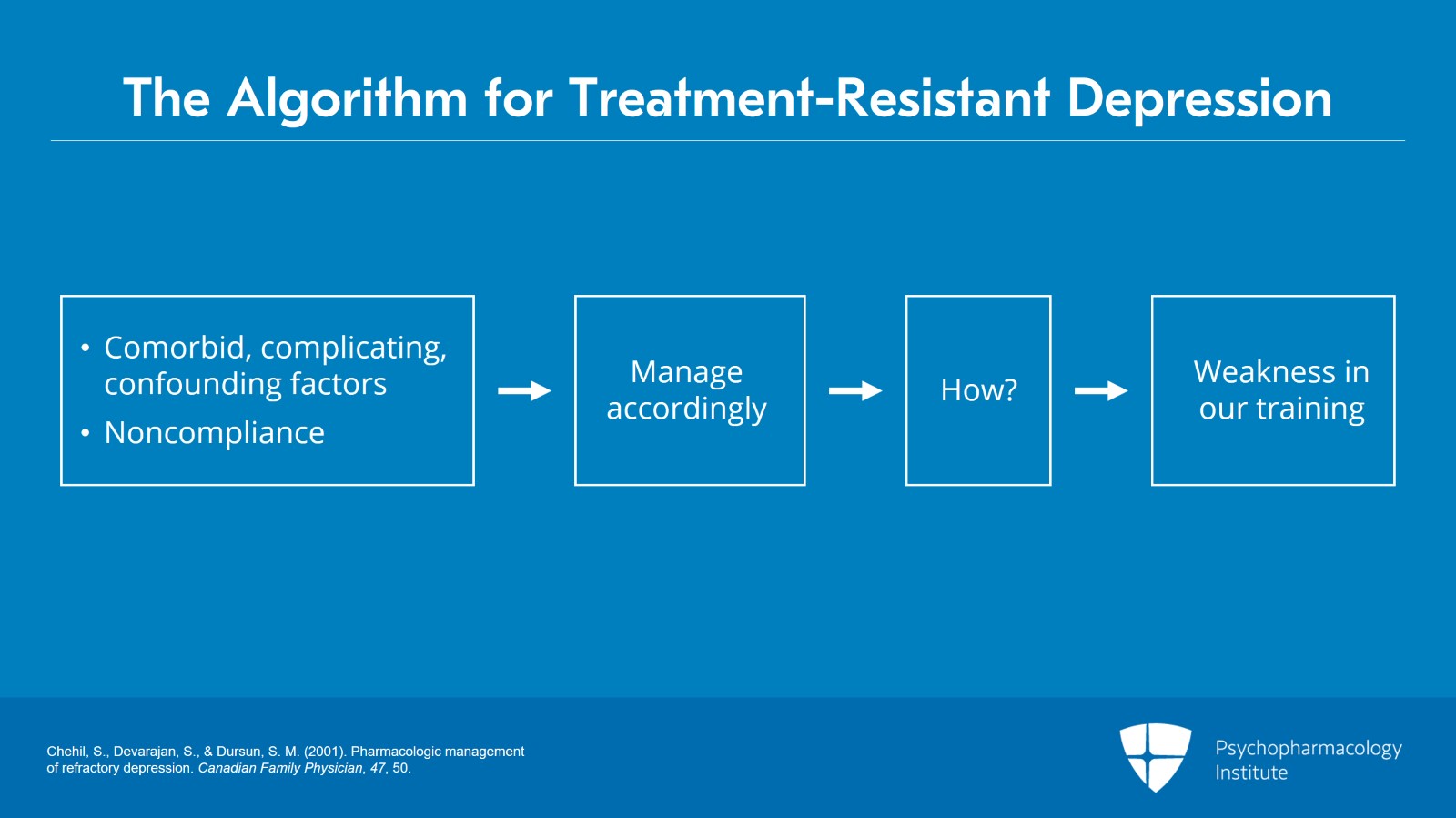

Audio Narration But what does the algorithm say you should do if comorbid factors are present, complicating, confounding factors, or there's noncompliance? The algorithm suggests we should “manage accordingly”. Now, I assume you're all ready to go home and manage your patients accordingly when they have those complicating and confounding factors. And of course not. How do you do that? So that is one of the weaknesses in our training, and that's what we're going to talk about.

References:

- Chehil, S., Devarajan, S., & Dursun, S. M. (2001). Pharmacologic management of refractory depression. Canadian Family Physician, 47, 50.

Slide 10 of 21

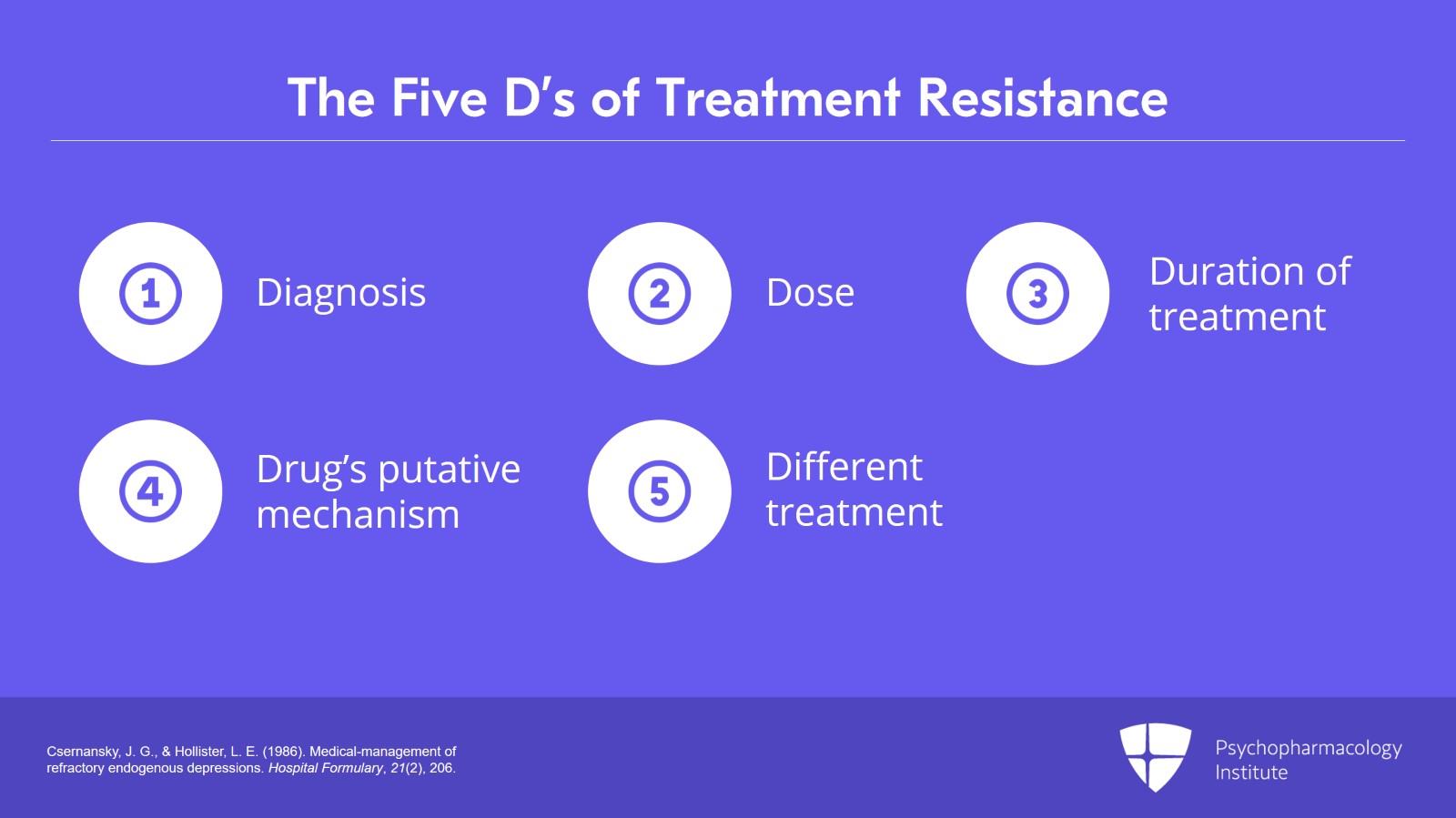

When I was in training I learned the model of Csernansky and Hollister, the five D's of treatment resistance, so: diagnosis, maximize the dose, make sure treatment is of adequate duration—but even those are complicated, because the optimal doses are not always clearly established, and you don't always have clarity around whether an adequate treatment is four weeks or 12 weeks. You'll certainly want to consider the putative mechanism of the drug. So, if you've already tried antidepressants with a certain mechanism and enough of those have failed, you want a different mechanism or different kinds of treatments, because there is evidence that switching medications to a different class may show greater benefit.

References:

- Csernansky, J. G., & Hollister, L. E. (1986). Medical-management of refractory endogenous depressions. Hospital Formulary, 21(2), 206.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 11 of 21

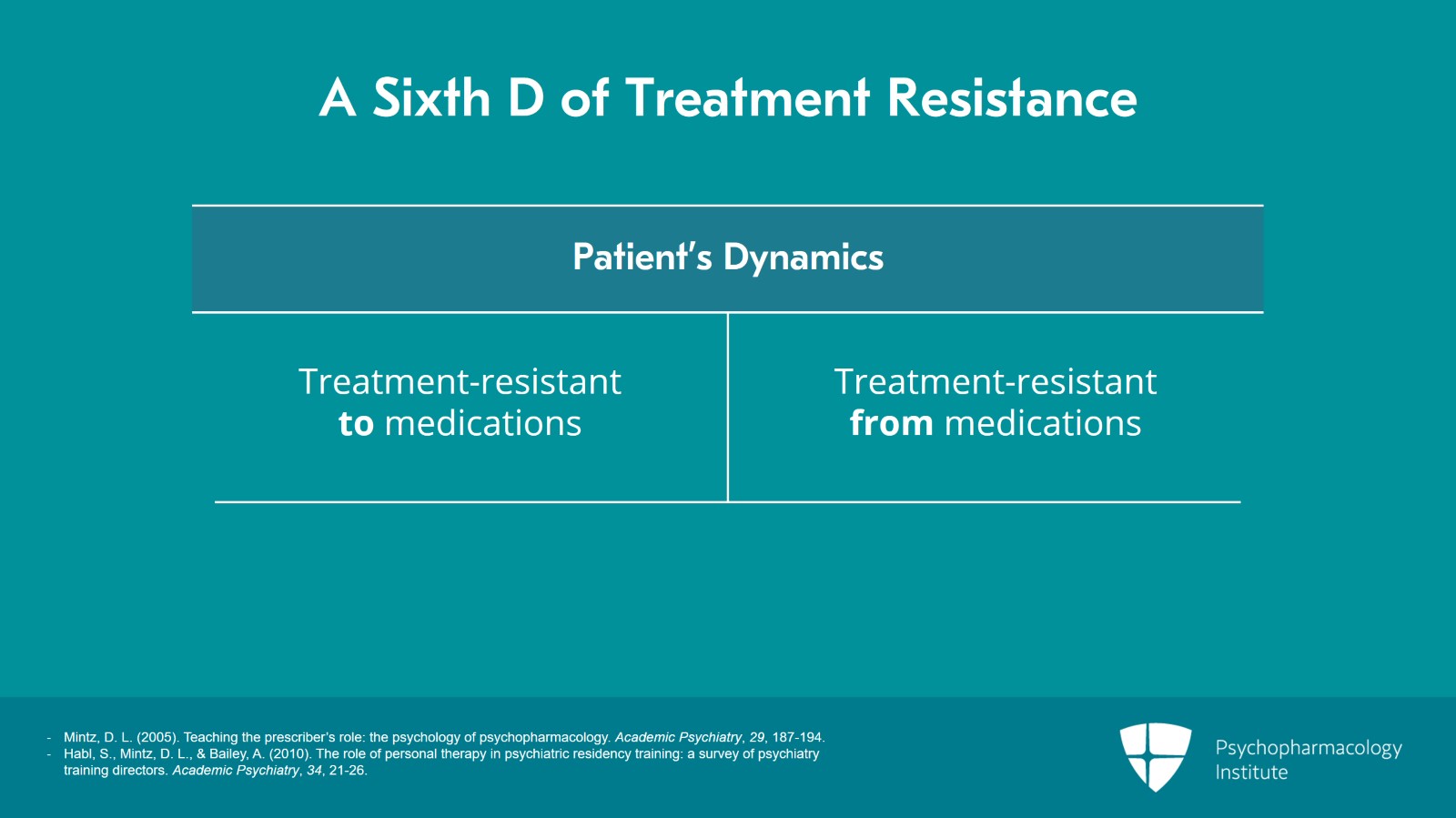

But the point I'm going to make is that there's a sixth D that we need to consider, which is the patient's dynamics. And when I think of the way that dynamics interfere with the patient's recovery, I tend to put that in my own mind into two different buckets: there are patients who are treatment resistant to medications and there are patients who are treatment resistant from medications. And there can be overlap—or patients with elements in both of those buckets.

References:

- Mintz, D. L. (2005). Teaching the prescriber’s role: the psychology of psychopharmacology. Academic Psychiatry, 29, 187-194.

- Habl, S., Mintz, D. L., & Bailey, A. (2010). The role of personal therapy in psychiatric residency training: a survey of psychiatry training directors. Academic Psychiatry, 34, 21-26.

Slide 12 of 21

Patients who are treatment resistant to medications typically are ambivalent about some aspect of the treatment. Often they're ambivalent about medications. They're worried about being harmed. They don't want to be dependent. They have lots of complicated feelings about medications that lead them either to not want to take the medications or to have adverse experiences.

References:

- Mintz, D. L. (2005). Teaching the prescriber’s role: the psychology of psychopharmacology. Academic Psychiatry, 29, 187-194.

- Habl, S., Mintz, D. L., & Bailey, A. (2010). The role of personal therapy in psychiatric residency training: a survey of psychiatry training directors. Academic Psychiatry, 34, 21-26.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 13 of 21

So, again, if the patient has stigmatized treatment it can lead, as I suggested, to repeated nonadherence to treatment recommendations, if patients are really ambivalent. Or, for patients who take the medications but are ambivalent these are patients who may be set up to experience higher levels of nocebo responses. And these patients I would contrast to patients who are treatment resistant from medications.

References:

- Mintz, D. L. (2005). Teaching the prescriber’s role: the psychology of psychopharmacology. Academic Psychiatry, 29, 187-194.

- Habl, S., Mintz, D. L., & Bailey, A. (2010). The role of personal therapy in psychiatric residency training: a survey of psychiatry training directors. Academic Psychiatry, 34, 21-26.

Slide 14 of 21

A more complicated kind of patient, but I think actually one of the more underappreciated aspects of psychiatric practice, patients who are treatment resistant from medications do not manifestly fear medications, they don't resist medications, and typically they actually present quite the opposite. They like medications. They want medications. Typically, often they want more medications in a way that, rather than leading to recovery, medications end up undermining the patient's healthy capacity to adapt, undercut their agency, or interfere with their development. For example, patients may use them in ways that they don't have to feel things that actually would be healthy to feel and would offer some guidance about how to operate in the world.

References:

- Mintz, D. L. (2005). Teaching the prescriber’s role: the psychology of psychopharmacology. Academic Psychiatry, 29, 187-194.

- Habl, S., Mintz, D. L., & Bailey, A. (2010). The role of personal therapy in psychiatric residency training: a survey of psychiatry training directors. Academic Psychiatry, 34, 21-26.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 15 of 21

And I think we know these patients often by our countertransference. You're sitting with a patient and they're telling you the medication works, they like it, it's helpful. We see that the patient feels better, but we also see that they don't seem to be getting better. The countertransference along with that is an uncomfortable feeling like you don't want to prescribe, you want to get the patient to take less medications, you perhaps feel like you're participating in something that is not helpful, or maybe even covertly perverse in some way. And so, we struggle with these patients, and it's hard, because the patients are reporting some benefits, maybe we can see those benefits, but we also recognize it's not really helping the patient move towards functional recovery.

References:

- Mintz, D. L. (2005). Teaching the prescriber’s role: the psychology of psychopharmacology. Academic Psychiatry, 29, 187-194.

- Mintz, D. (2022). Psychodynamic psychopharmacology: caring for the treatment-resistant patient. American Psychiatric Pub.

Slide 16 of 21

It's always complicated to quote Freud when you're talking to an audience of people that are primarily pharmacotherapists, but I do want to go back to what something Freud said in 1905: "We, physicians, cannot discard psychotherapy if only because another person intimately concerned in the process of recovery, the patient, has no intention of discarding it“. He wanted to say that “a factor dependent on the psychical disposition of the patient contributes, without any intention on our part, to the effect of every therapeutic process initiated by a physician”.

References:

- Freud, S. (1971). On psychotherapy (1905). PsycEXTRA Dataset.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 17 of 21

Freud is talking about the placebo response but then he goes on to say: “but often it acts as an inhibition.” So that's what we talk about, the ways that the psychological aspects of treatment or the patient's relationship to treatment interfere actually with recovery. So, Freud goes on to say that “all physicians, therefore yourselves included, are continually practicing psychotherapy even when you have no intention of doing so and are not aware of it”. However we talk to the patient is having also a psychological effect that is either helping the medications to work better or hindering the patient's recovery.

References:

- Freud, S. (1971). On psychotherapy (1905). PsycEXTRA Dataset.

Slide 18 of 21

“It is a disadvantage”—he goes on to say—“however, to leave the mental factor in your treatment so completely in the patient's hands. Thus, it is impossible to keep a check on it, to administer it in doses or to intensify it. Is it not then a justifiable endeavor on the part of a physician to seek to obtain command of this factor, to use it with a purpose, and to direct and strengthen it?” And, over the course of the rest of these talks, we're going to be thinking about how a physician might seek to obtain command of this factor to use it with a purpose, and direct and strengthen it in ways that promote the patient's healthy use of medications.

References:

- Freud, S. (1971). On psychotherapy (1905). PsycEXTRA Dataset.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 19 of 21

So, to summarize the key points: Despite major neuroscientific advances, there is little evidence of improved outcomes in psychiatric patients. There may be fewer side effects, or medications may be more tolerable, but our patients are really not getting better at a substantially higher rate than they were 30 years ago.

Slide 20 of 21

We know with complicated patients we need all of our tools, biomedical and psychosocial, to achieve optimal outcomes. And, it is useful to be able to understand and address psychological and interpersonal dynamics that interfere with the patient's healthy use of medications.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.