Slides and Transcript

Slide 1 of 12

Colleagues, now that we’ve talked about measurement-based care, well let’s focus now on the goals of treatment which have to do with things like remission and functional recovery but also, and this is a major point, on the prevention of relapse and recurrence in older adults with major depression. I like to say to my patients getting well is important but it’s not enough. Staying well is also important.

Slide 2 of 12

The goal of treating clinical depression in older adults, a better life and hopefully also a longer life.

We’re interested in achieving symptomatic remission. We want to promote functional recovery because that matters a great deal to both patients and their family caregivers. We want to prevent relapse and recurrence and the evolution of a chronic more treatment-refractory form of depression.

We are interested in attenuating, delaying or preventing the downstream consequences of depression including dementia and we hope obviously to prevent suicide.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 3 of 12

You also want to reduce caregiver burden. My philosophy is that the treatment of depression in older adults should be both patient focused but also family centered.

Finally and very importantly, we want to facilitate the appropriate use of general medical and social case work services.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Slide 4 of 12

Another way of saying this is that depression in older adults rarely occurs in pure culture. It is almost always associated with co-occurring medical and psychosocial problems. Team-based approaches to treatment enable the co-occurring medical and social problems to be addressed by colleagues with appropriate domain-specific expertise.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 5 of 12

So why do we care about remission of symptoms?

Not just response but remission of symptoms which as I’ve mentioned before is generally indicated by a PHQ-9 score of less than 5 and hopefully close to 0.

Well, remission of symptoms is the first goal from my clinician’s perspective of treating major depression in older adults because response without full symptomatic remission continues to be associated with disabling symptoms, with suffering, with functional impairment and with a higher risk for relapse and recurrence as well as for inappropriate healthcare utilization.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Slide 6 of 12

There is also in connection with my dictum of taking a long-term perspective on the treatment of depression in older adults, long-term treatment is necessary to prevent relapse and recurrence because very often depression in older adults is subject to high rates of relapse and recurrence.

Looking at this from a neuroscience perspective, there is abundant evidence that treatment may promote brain health and possibly reduce the risk for dementia. The data or the jury is still all out on that question but I think it’s reasonable to suggest that as a hypothesis.

Finally, and this is of particular interest I think, there is some evidence that appropriate treatment of depression in older adults may actually enhance not only the quality of life but prolong life as well, as well as reduce the risk for completed suicide.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 7 of 12

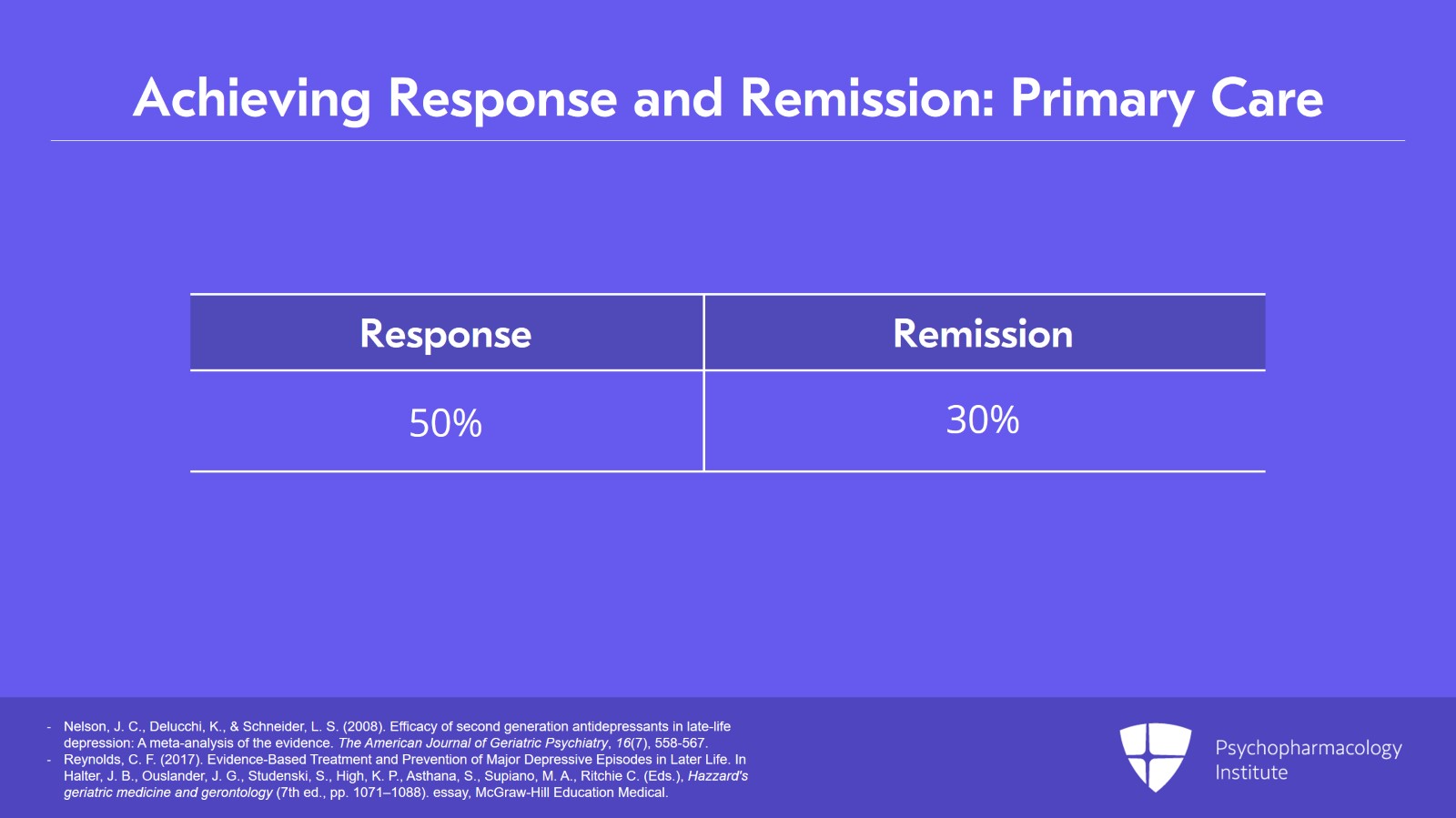

Colleagues often wonder given how busy clinicians are in their day-to-day service how feasible it is actually to achieve full-blown symptomatic remission.

Again, there is good data on this point. In primary care settings, for example, where most older adults receive treatment for depression if they receive it at all, using what are called collaborative care models, response is achieved with first-line treatments in about 50% of patients and remission in about 30%.

References:

- Nelson, J. C., Delucchi, K., & Schneider, L. S. (2008). Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: A meta-analysis of the evidence. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(7), 558-567.

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Slide 8 of 12

But the overall rates of response and remission can be substantially increased with, for example, the further use of add-on strategies, augmentation strategies such as adding a second medication or switching classes of medication or through the combination of medication and depression-specific counseling or psychotherapy.

And as my colleagues point out, there are frequently medical or environmental factors that can represent barriers to full response and remission but where partial response may still occur.

References:

- Nelson, J. C., Delucchi, K., & Schneider, L. S. (2008). Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: A meta-analysis of the evidence. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(7), 558-567.

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 9 of 12

I find it very helpful, if not indeed essential, to engage family caregivers in discussions about treatment to optimize treatment adherence and to help with environmental and psychosocial stressors. Also, in the spirit of team-based care, I will frequently consult colleagues and social work to help connect my patients with needed social resources in the community.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Slide 10 of 12

So, to summarize the key points, we’re talking about the fact that the goal of treating depression in older adults should include remission of symptoms as well as restoration of a sense of well-being and ability to function in major social and familial roles. This is what truly matters to patients and to those who love them and give them care. But getting well is not enough. It’s staying well that counts because of the high propensity of depression in old age to follow a relapsing and recurrent course.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 11 of 12

As we’ll talk about in subsequent video chats as part of this lecture series, you will find that I emphasize that the dose of medication that gets you well is also the dose that keeps you well. Corollary to this is that if a second agent is needed in addition to the first to bring about remission, it should be continued as well to prevent relapse and recurrence.

Thank you.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.