Slides and Transcript

Slide 1 of 19

Hi. This is our next video on nonpharmacologic strategies for managing agitation and let's really focus on calming techniques especially verbal de-escalation.

Slide 2 of 19

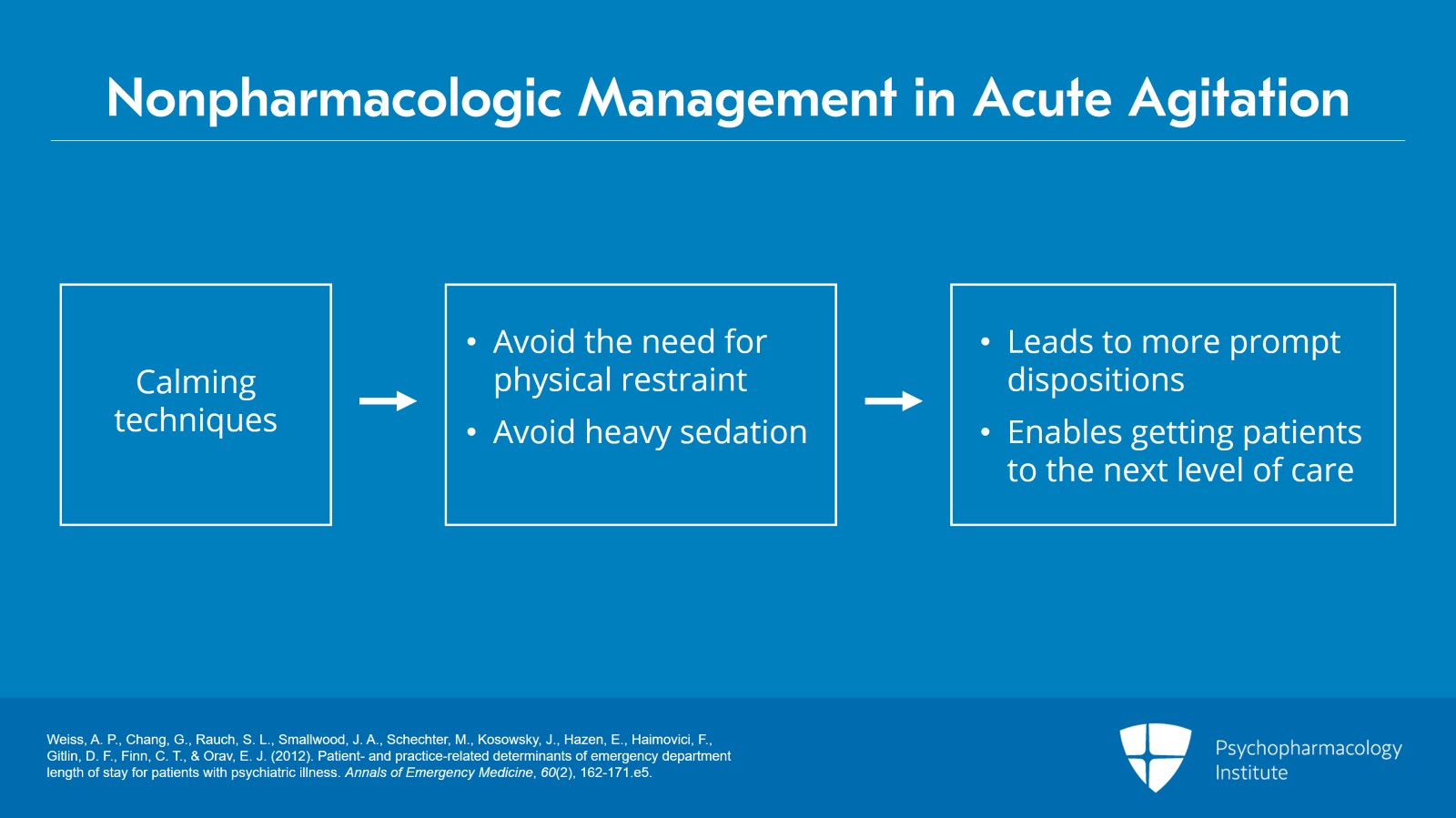

So, nonpharmacologic management of an individual who has acute agitation. First, recognize that if we use calming techniques, especially verbal de-escalation, we can avoid the need for physical restraints and avoid the need to heavily sedate people the vast majority of the time. And that's going to help us in many ways and certainly help to lead to more prompt dispositions, getting people on their way to that next level of care.

References:

- Weiss, A. P., Chang, G., Rauch, S. L., Smallwood, J. A., Schechter, M., Kosowsky, J., Hazen, E., Haimovici, F., Gitlin, D. F., Finn, C. T., & Orav, E. J. (2012). Patient- and practice-related determinants of emergency department length of stay for patients with psychiatric illness. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 60(2), 162-171.e5.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 3 of 19

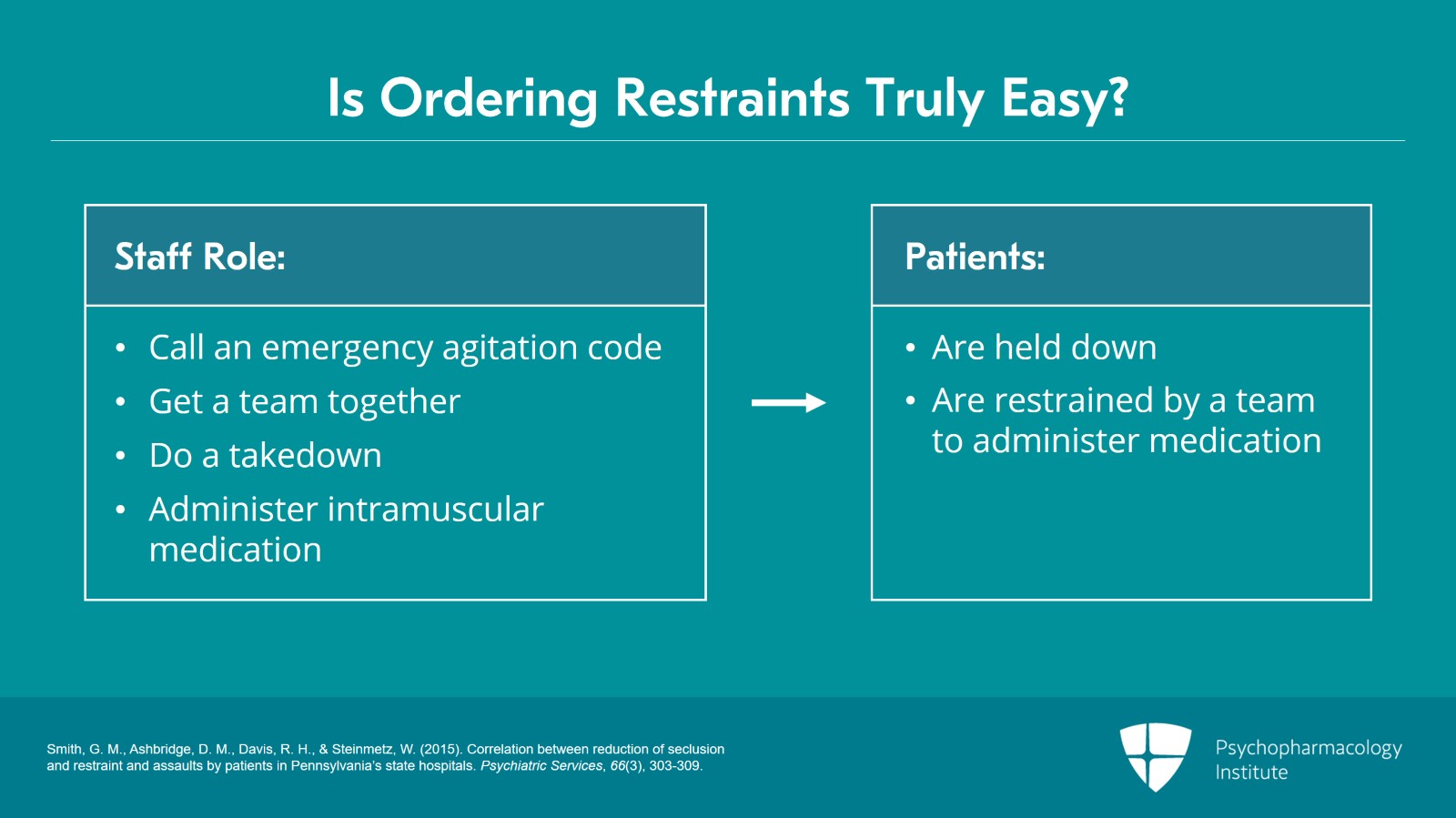

So, because of that, it's really worth the short amount of time to attempt verbal de-escalation, and I've had a lot of people tell me, oh, it's easy for me to just write an order for patients to be put into restraints and to give them some parenteral medication and I can go on to my other cases, and we're very busy in our emergency department.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Slide 4 of 19

And I can point out as a comparison to that, maybe that's easy for you as the prescriber, but what about the rest of your staff, because they're going to be calling an emergency agitation code. And then they're going to get a team together, and they're going to surround the patient, and they're going to end up doing a takedown where the people are jumping on top of a person trying to hold them down. Patients finally get held down, and they get moved to a gurney or to a bed, and they get put into physical restraints, wrists, ankles, one across the belly, held down. The staff member goes, draws up some intramuscular medication, takes some time to get that prepared, and comes back to where the patient is in restraints. They get a team together again so they can hold the person down so they can pull their pants down and give them one, two, maybe three injections into their bare rear end.

References:

- Smith, G. M., Ashbridge, D. M., Davis, R. H., & Steinmetz, W. (2015). Correlation between reduction of seclusion and restraint and assaults by patients in Pennsylvania’s state hospitals. Psychiatric Services, 66(3), 303-309.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 5 of 19

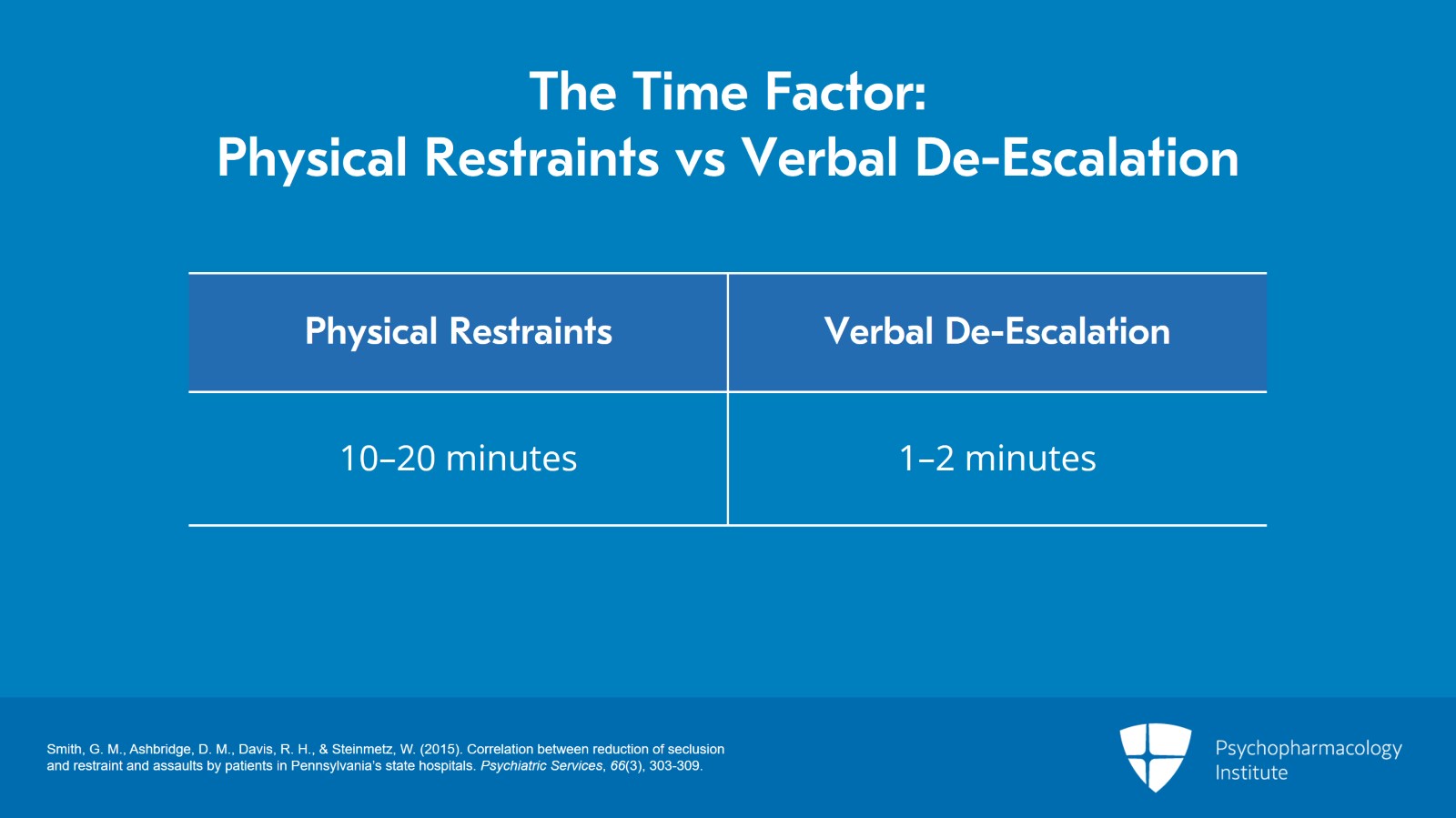

And how much time did that take compared to you saying you didn't have any time, so you just wrote the order? Well, a lot of your staff just spent 10, 20 minutes. Collectively, you're talking about hours of staff time because you felt that you didn't have enough time to try de-escalation for a minute or two. So that's a big difference, and it's worth always the short amount of time to attempt verbal de-escalation.

References:

- Smith, G. M., Ashbridge, D. M., Davis, R. H., & Steinmetz, W. (2015). Correlation between reduction ofseclusion and restraint and assaults by patients in Pennsylvania’s state hospitals. Psychiatric Services, 66(3), 303-309.

Slide 6 of 19

What we know in a really good study is that if you put somebody in restraints in the hospital emergency department, that's going to make sure that they're going to stay on average more than four hours longer than people that didn't go on restraints. And what is it worth to you to have that bed available four hours earlier with your constant flow of patients coming into your emergency setting? That makes it worth it.

References:

- Weiss, A. P., Chang, G., Rauch, S. L., Smallwood, J. A., Schechter, M., Kosowsky, J., Hazen, E., Haimovici, F., Gitlin, D. F., Finn, C. T., & Orav, E. J. (2012). Patient- and practice-related determinants of emergency department length of stay for patients with psychiatric illness. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 60(2), 162-171.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 7 of 19

That might be a logistical reason or a hospital-side reason to do it. The main reason is it's much more humane. It's much more ethical to avoid restraints in individuals. It can be devastating to somebody to be tied down in restraints. If you don't believe it, have people put you in there and see how it feels. It’s a pretty awful and vulnerable feeling to have your arms, legs, and belly tied down, and you’re not able to do anything, you can't protect yourself, you're very vulnerable and it's not a great feeling. And, if you need to refer a person with a behavioral emergency out to an inpatient psychiatric facility, they're going to be far more likely to accept that transfer than if you've had somebody who's in restraints. In fact, a lot of psychiatric hospitals, if you call them up and they say like, well, what's the patient doing right now, and you say, well, they're in restraints, they'd say, well, call back when they're out of restraints, we don't take people who are restrained. So, avoiding that is going to have benefits for the patient. It’s going to have benefits for you. It’s going to have benefits for your emergency department and emergency setting hospital as a whole.

References:

- Smith, G. M., Ashbridge, D. M., Davis, R. H., & Steinmetz, W. (2015). Correlation between reduction of seclusion and restraint and assaults by patients in Pennsylvania’s state hospitals. Psychiatric Services, 66(3), 303-309.

Slide 8 of 19

And, if you're not seeing any kind of improvement or chance to keep going after a minute or two of verbal de-escalation, yeah, then go ahead and maybe default to some other things, but always try, even in people who are really, really agitated. I can tell you from having seen over 90,000 emergency psych patients in my career it's always worth the effort. And sometimes, it'll surprise you. The people you thought least would respond to it actually respond to it really, really well.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 9 of 19

So, using de-escalation and calming techniques is always indicated. Hopefully, you can avoid getting somebody to that situation where you feel like you have no alternative to restraints. I've seen this note too many times in charts; We attempted de-escalation, and it failed so we went to restraints and medication. That should not be your mindset. Your mindset should be we're continually doing de-escalation.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Slide 10 of 19

And that's assisting us to proceed with our psychiatric eval, our medical eval, and offering medications, and all these things combined help us to avoid seclusion and restraint.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 11 of 19

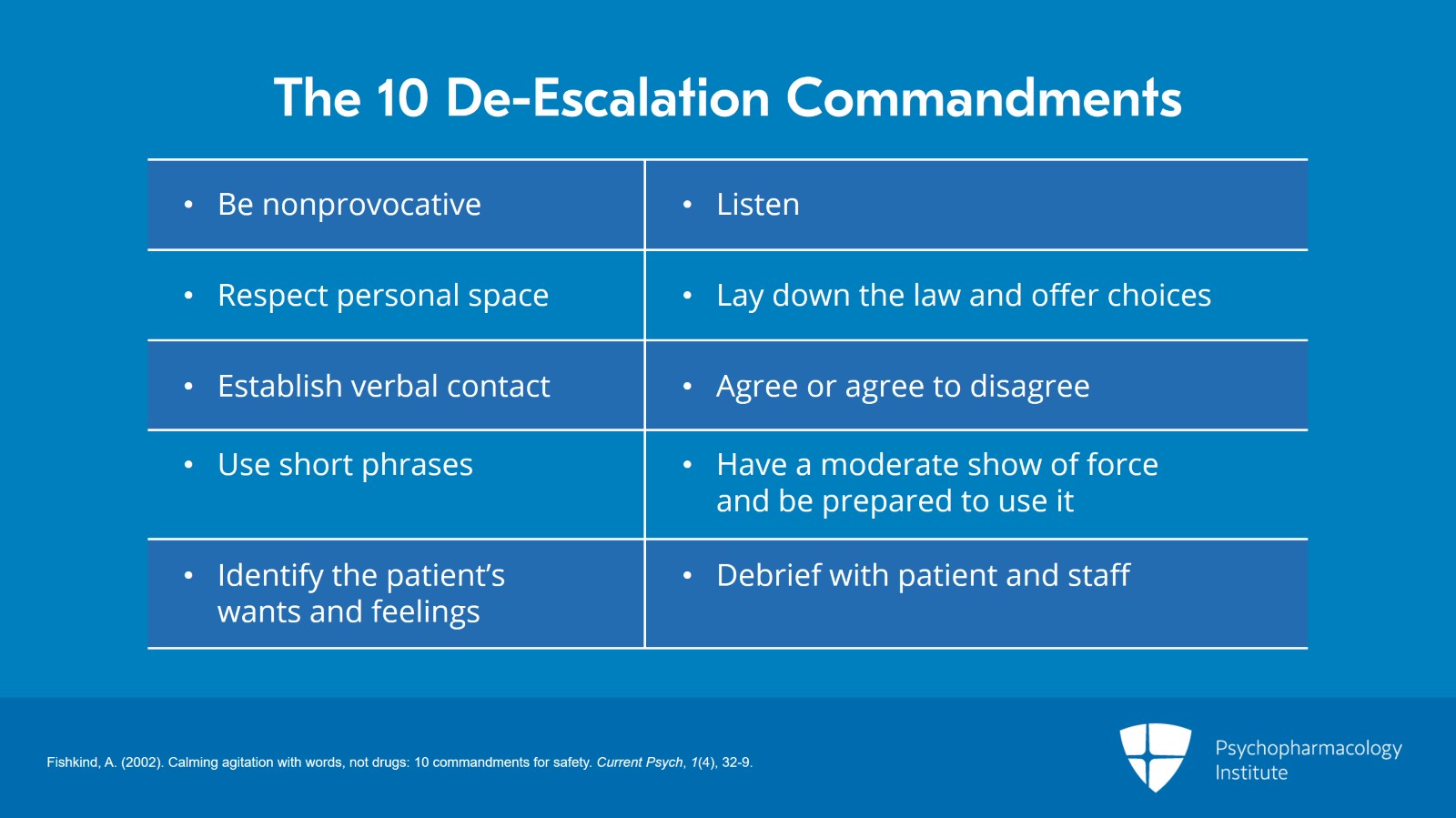

So, there's a basic set of concepts to doing de-escalation that are known as the 10 De-escalation Commandments. These were created by a brilliant emergency psychiatrist known as Avrim Fishkind about two decades ago, and they have stood the test of time and are used in hospitals around the world. We can probably do 10 videos on each part of the 10 De-escalation Commandments, but for the sake of time here, you can see these on your screen in front of you; Give them plenty of space, be the person who intervenes, identify that person's wants and feelings, be the person who listens.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Slide 12 of 19

I think if you really had to think about them collectively, the idea is if somebody's agitated, don't be agitated back to them. You be the calm one. Be calm when they're loud, have your arms at your side while they're clenching their fists. When they’re screaming, you're whispering.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 13 of 19

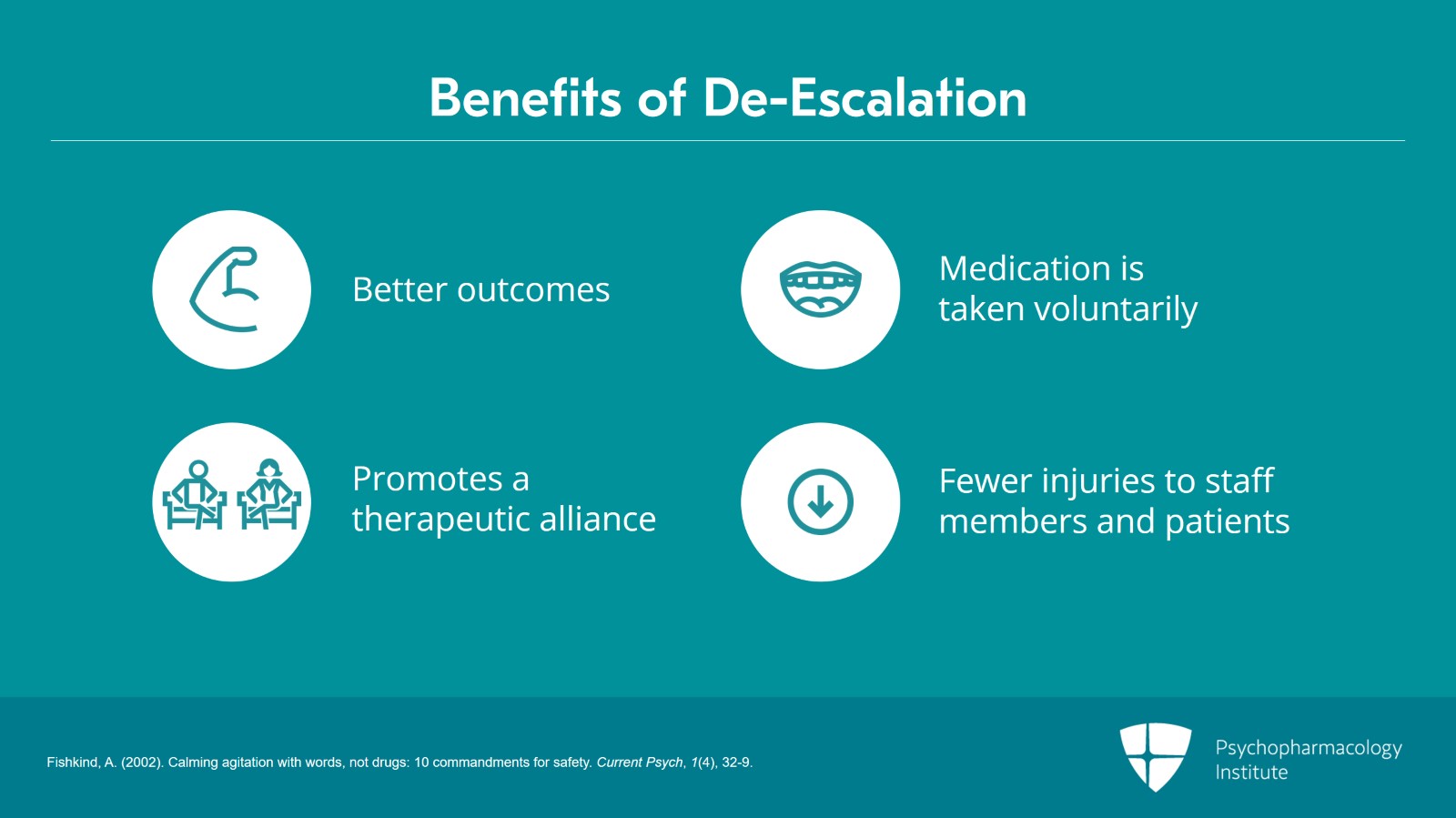

And by doing that, you're going to have far better outcomes, and a much more opportunity to get people to take medications voluntarily. Recognize that nobody ever got injured by a fingerstick by giving oral meds. You’re going to have a therapeutic alliance with patients, generate trust, and actually be able to have a collaborative method of working with people who have acute behavioral health conditions. People are going to get better without you having to resort to calling a code and putting you and your colleagues at risk. If you avoid those restraints and medication procedures, you're going to have far fewer injuries for both your staff members and your patients.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Slide 14 of 19

Are there going to be times when there are patients who are going to need restraining and forcibly medicating them? Of course. But the vast majority of the time, they don’t. And if you're able to work with them and really defaulting to the therapeutic alliance, offer oral meds instead of forcible injectable meds, work with somebody and help them to calm down as opposed to getting the security team together and forcibly putting them into restraints, all these have much better outcomes.

References:

- Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych, 1(4), 32-9.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 15 of 19

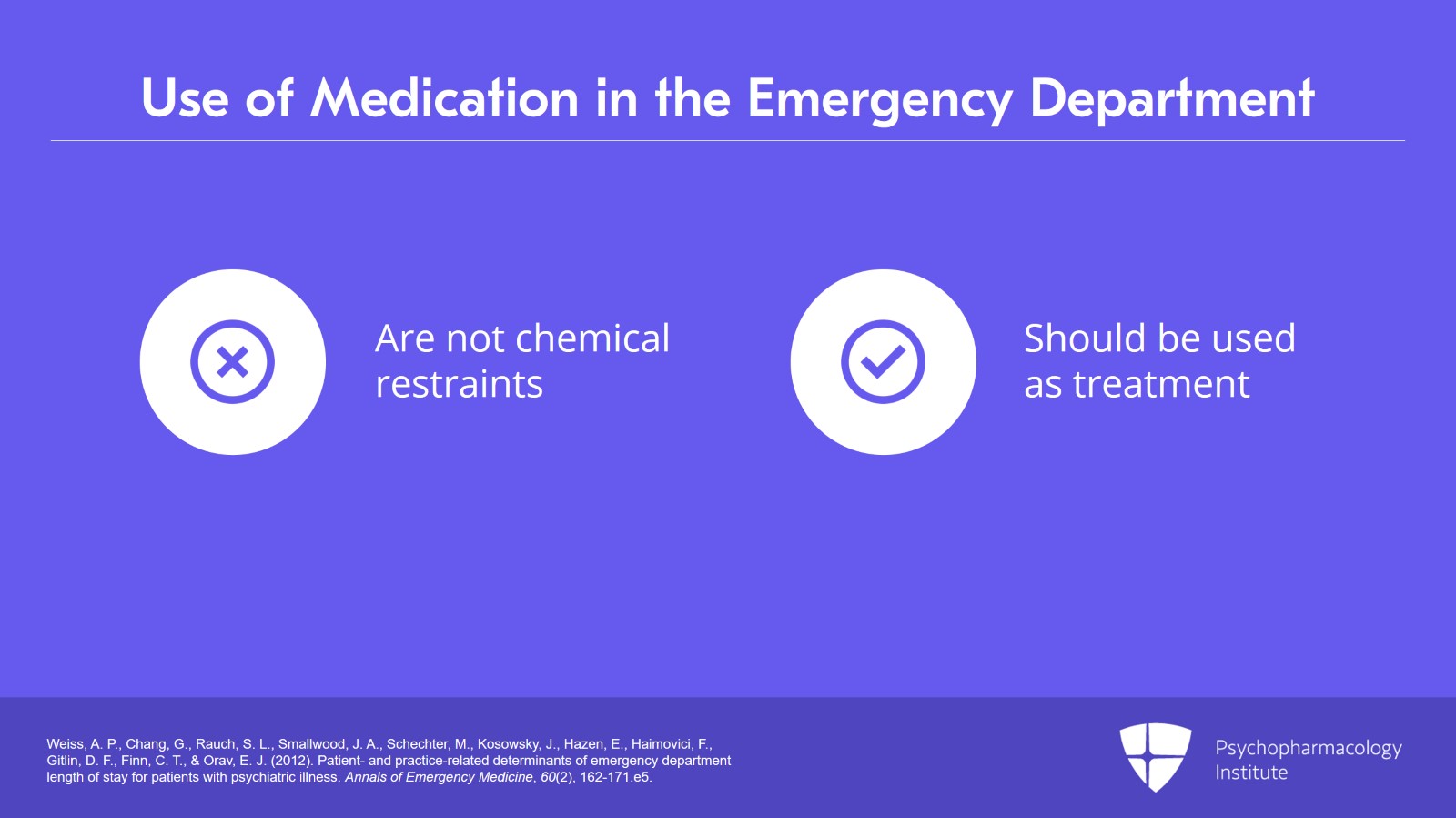

The other thing that you want to do with somebody who is agitated is begin appropriate medications in the emergency department, and that's something we're going to talk about in some of the later videos, but recognize that medications in the ED are not chemical restraints and that you should be thinking of the medications as treatment, and appropriate medications, and we'll explain that in a little bit. When you're starting medications, and you're avoiding putting people in restraints, that can have incredible benefits for your treatment team and your flow and your throughput in your emergency setting.

References:

- Weiss, A. P., Chang, G., Rauch, S. L., Smallwood, J. A., Schechter, M., Kosowsky, J., Hazen, E., Haimovici, F., Gitlin, D. F., Finn, C. T., & Orav, E. J. (2012). Patient- and practice-related determinants of emergency department length of stay for patients with psychiatric illness. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 60(2), 162-171.e5.

Slide 16 of 19

So, to sum up, our key points are: Calming techniques and de-escalation can truly avoid putting people in restraints and avoid giving those heavy sedating meds that can lead to people being unconscious for long hours unnecessarily. Instead, we're going to lead to more prompt dispositions, and it's going to be well worth the short amount of time to attempt calming techniques and verbal de-escalation. Remember that verbal de-escalation usually takes far less time than the process of putting somebody into restraints and giving involuntary parenteral medications.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 17 of 19

When we do give meds in the emergency department, those are not chemical restraints, but instead, that’s part of a treatment plan, and that’s also going to help facilitate a prompt transfer to psychiatric facilities, and it's going to reduce the time in the emergency department. And the time in the emergency department is going to be considered treatment rather than just screen and refer.

Slide 18 of 19

And by avoiding those containment takedown procedures, we're going to result in far fewer injuries to staff members and patients, and we're going to end up having a much better relationship with our patients as a result.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.