Slides and Transcript

Slide 1 of 15

I’d like to talk to you a little bit about nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its consequences partly because this is increasingly becoming the most common cause of end-stage liver disease.

Many patients now have been treated for their hepatitis C. Of course, people will always drink alcohol. But more and more in our country which is highly dysmetabolic, we see this as resulting in end-stage liver disease.

Slide 2 of 15

So, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease represents a spectrum of illness going from essentially asymptomatic fat or what we call steatosis all the way to the inflamed liver with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis which is also called NASH.

In addition to being highly prevalent, it’s certainly going to be so among those who are obese.

And this is not surprising because we think part of the pathophysiology is insulin resistance which is often highly correlated with obesity.

References:

- Merrell, M. D., & Cherrington, N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 43(3), 317-334.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 3 of 15

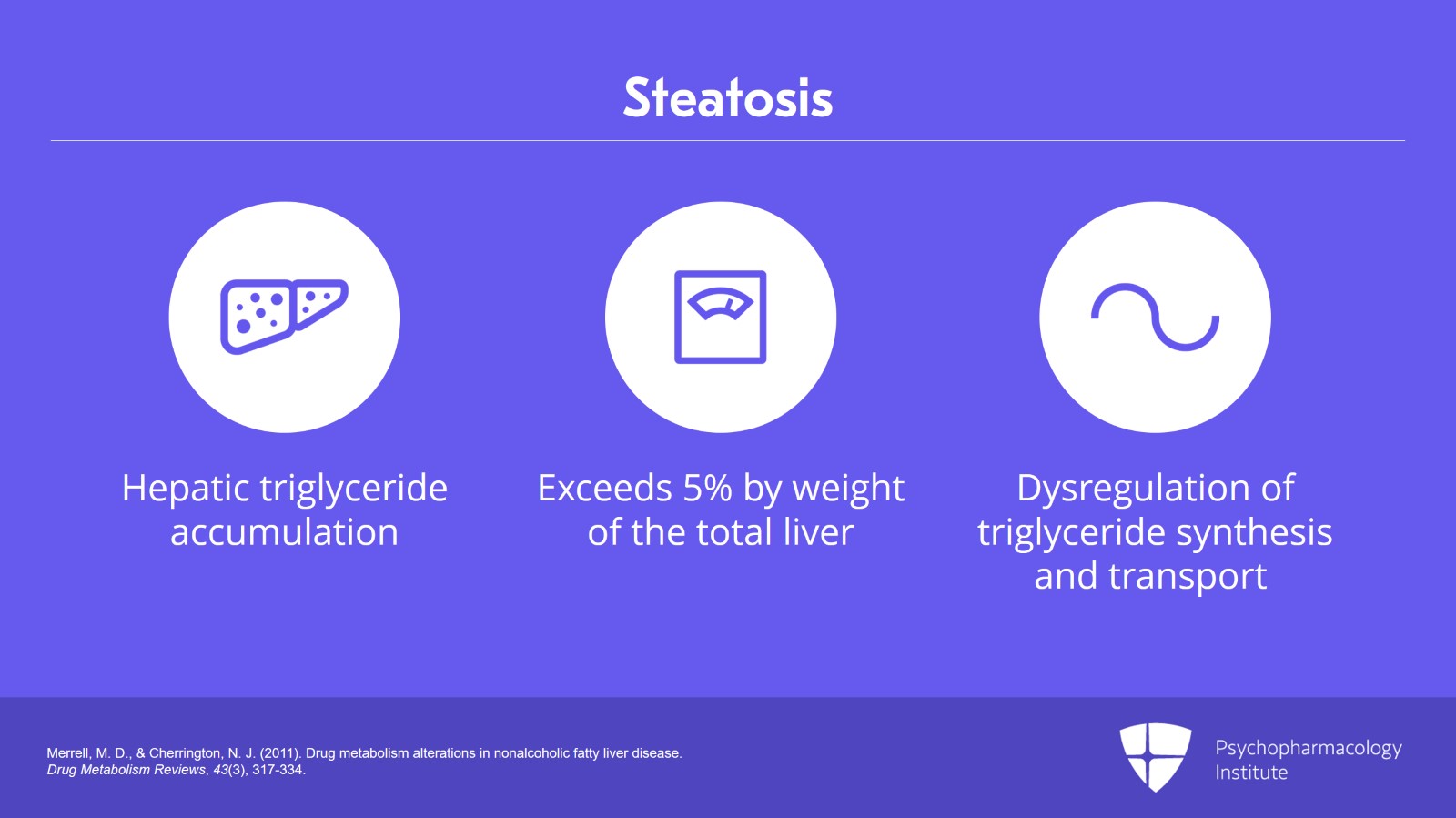

Steatosis is defined as the hepatic triglyceride accumulation which exceeds 5% by weight of the total liver. The pathogenesis is due to dysregulation of triglyceride synthesis and transport.

And you should note that about 60% of hepatic fat content comes from circulating fatty acids and not just dietary ingestion.

References:

- Merrell, M. D., & Cherrington, N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 43(3), 317-334.

Slide 4 of 15

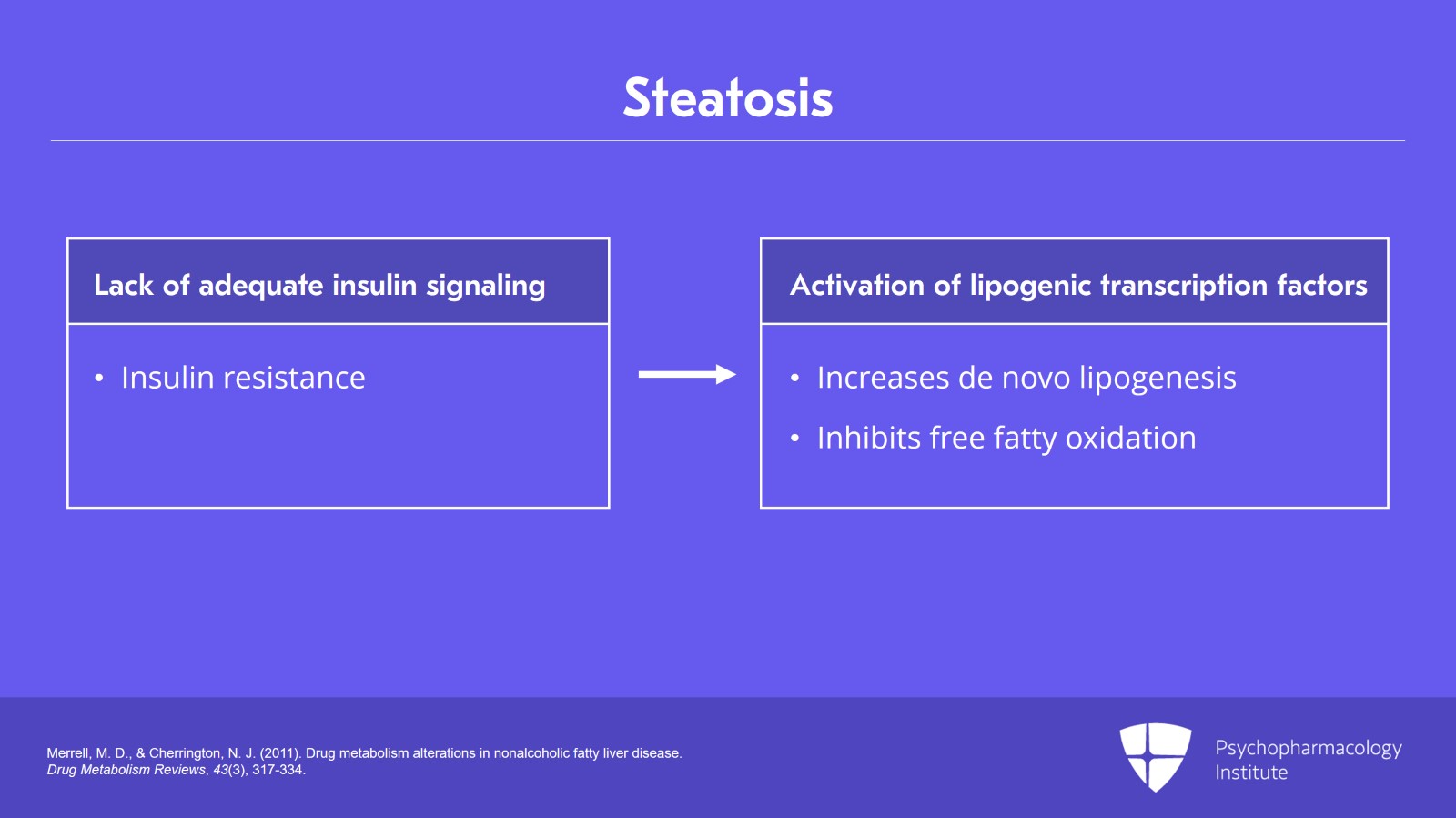

And again, the core aspect of this is lack of adequate insulin signaling. These people are insulin resistant, and we think this is part and parcel of what relates to the development of these problems.

Insulin resistance causes activation of lipogenic transcription factors that increase de novo lipogenesis and inhibit free fatty oxidation. This is the same reason why people who are dysmetabolic with metabolic syndrome or have diabetes have high triglycerides. It’s really the same process.

References:

- Merrell, M. D., & Cherrington, N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 43(3), 317-334.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 5 of 15

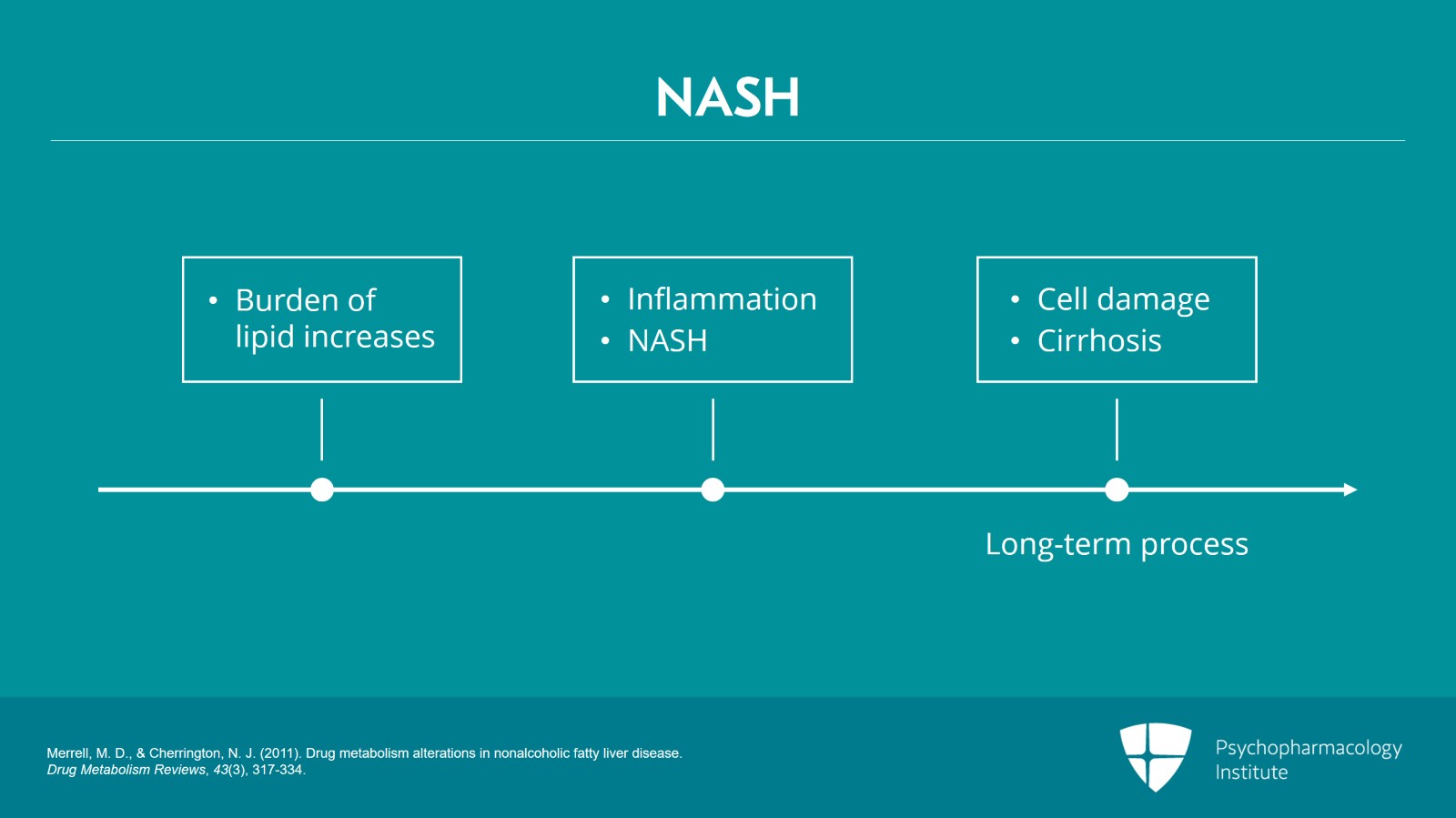

Just having a higher-than-normal fat content in your liver does not necessarily cause injury.

But what happens is as the burden of lipid increases you eventually start to get inflammation which is called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH.

And as you all know, persistent inflammation eventually causes cell damage, and this is going to cause cirrhosis. It is a long-term process clearly, but this is what happens over time, over years in the same way, to be honest, that people with persistent hepatitis C eventually develop cirrhosis. Initially, they’re asymptomatic. They have some inflammation. But over years and years, eventually they lose tissue and develop cirrhosis.

The same thing here with NASH, just a different cause of the inflammation.

References:

- Merrell, M. D., & Cherrington, N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 43(3), 317-334.

Slide 6 of 15

As the fibrosis evolves into portal and periportal regions causing bridging, we’re now going to have somebody who really has the same pathology as an individual with untreated hepatitis C, persistent active hepatitis C or the patient who continues to drink alcohol.

References:

- Merrell, M. D., & Cherrington, N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 43(3), 317-334.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 7 of 15

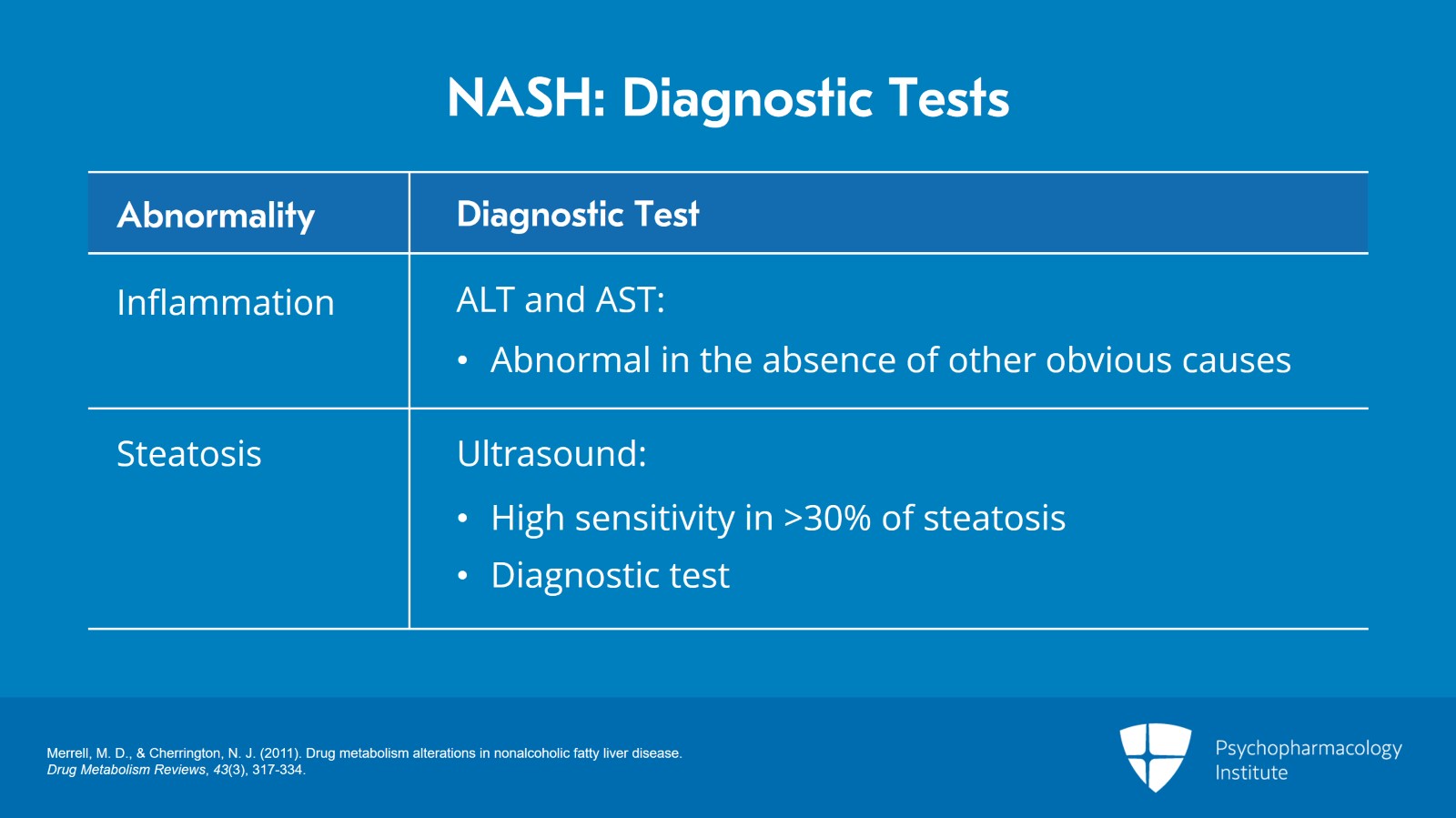

So, what are the diagnostic tests to suspect this? And the reason I’m bringing this up at this point of the lecture is that you will see abnormalities on their liver function tests and inflammation is the signal here that they may have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

How do we diagnose inflammation? We will see abnormal ALT and AST in the absence of other obvious causes. The follow-up test of course is going to be an ultrasound. It has high sensitivity in patients who have more than 30% steatosis and it is diagnostic.

References:

- Merrell, M. D., & Cherrington, N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 43(3), 317-334.

Slide 8 of 15

Again, inflammation by itself does not alter drug kinetics. It’s when you get cirrhosis that you start to have problems.

The one exception might be regulation of the P450 enzyme 1A2.

People who have significant inflammatory conditions, an active infection such as COVID, I mean, a serious infection where you’re in the hospital, other bacterial infections, those patients may have lower than normal P450 1A2 activity. It does not really affect other cytochrome enzymes until you have loss of tissue architecture due to cirrhosis.

References:

- Morgan, D. J., & McLean, A. J. (1995). Clinical pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic considerations in patients with liver disease. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 29(5), 370-391.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 9 of 15

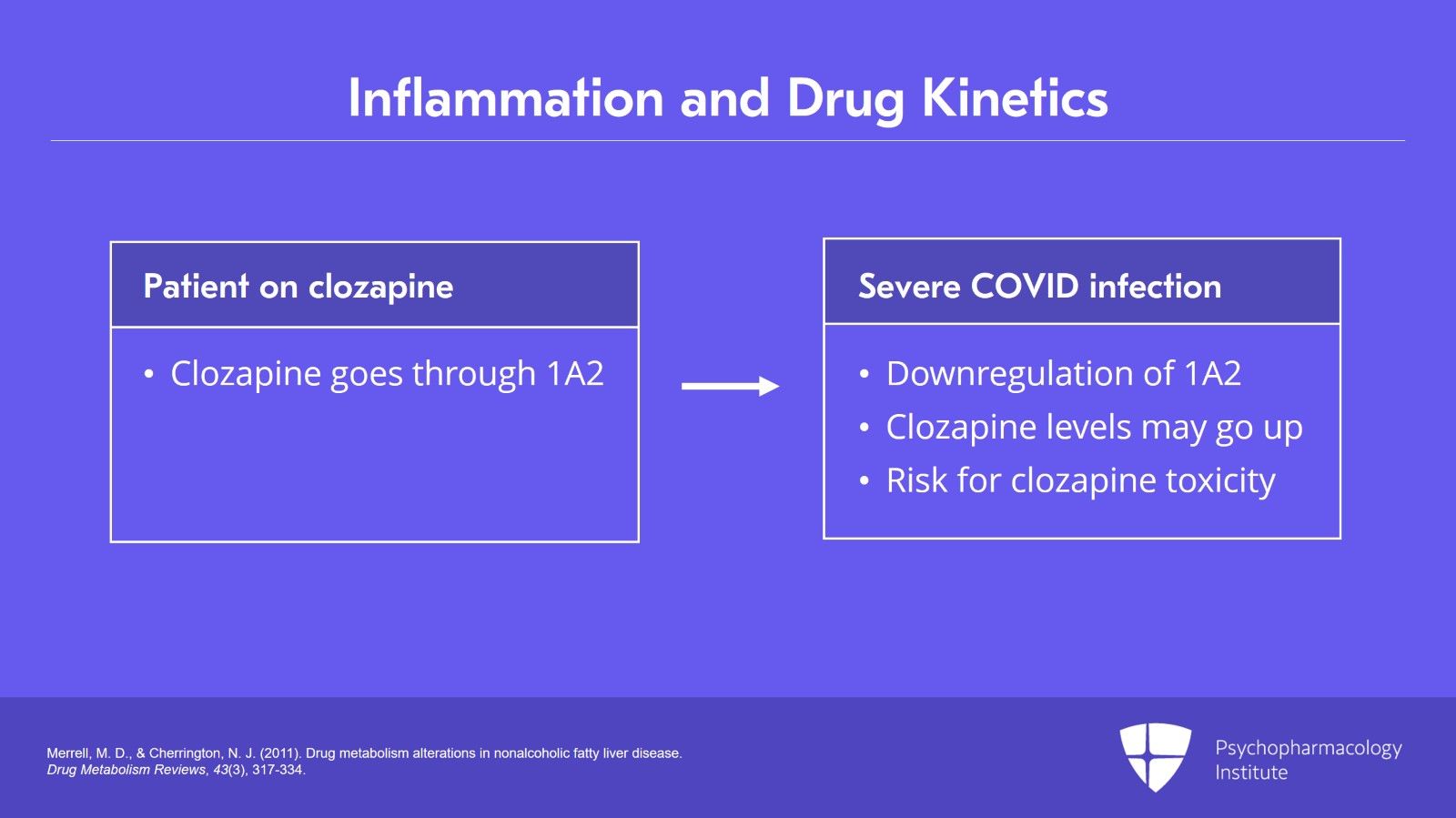

So again, you’ve heard maybe about patients who are on clozapine which goes through 1A2 who’ve had toxicity when they get admitted to the hospital with a severe COVID infection. At that point, there is downregulation of the 1A2, and the clozapine levels may go up three- or four-fold.

Again, you have to have a serious illness to get this kind of cytokine release. People who are asymptomatic COVID positive are unlikely to have this type of effect. It’s the individual who really is manifesting systemic symptoms who we will see and might be at risk for clozapine toxicity.

References:

- Merrell, M. D., & Cherrington, N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 43(3), 317-334.

Slide 10 of 15

The most common LFT abnormality is really going to be ALT and AST abnormalities. But in fact, these have nothing to do with the patient’s ability to metabolize drugs through the liver.

When you do not have cirrhosis, drug pharmacokinetics are generally preserved. And really, what you have to do now when you see these abnormal labs is to try to figure out what’s going on.

If it’s just AST and ALT, we have 25 years of research which really indicates that pharmacokinetics are not altered in the absence of cirrhosis.

References:

- Morgan, D. J., & McLean, A. J. (1995). Clinical pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic considerations in patients with liver disease. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 29(5), 370-391.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 11 of 15

So, the classic paper by Morgan and McLean which is referenced for this lecture looked at chronic active hepatitis of various forms, primary or secondary liver cancer, schistosomiasis. And what they found is inflammation by itself does not alter drug kinetics. It is cirrhosis. So, this is perhaps the most important take-home point of all the lecture. It’s cirrhosis which determines drug kinetics.

References:

- Morgan, D. J., & McLean, A. J. (1995). Clinical pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic considerations in patients with liver disease. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 29(5), 370-391.

Slide 12 of 15

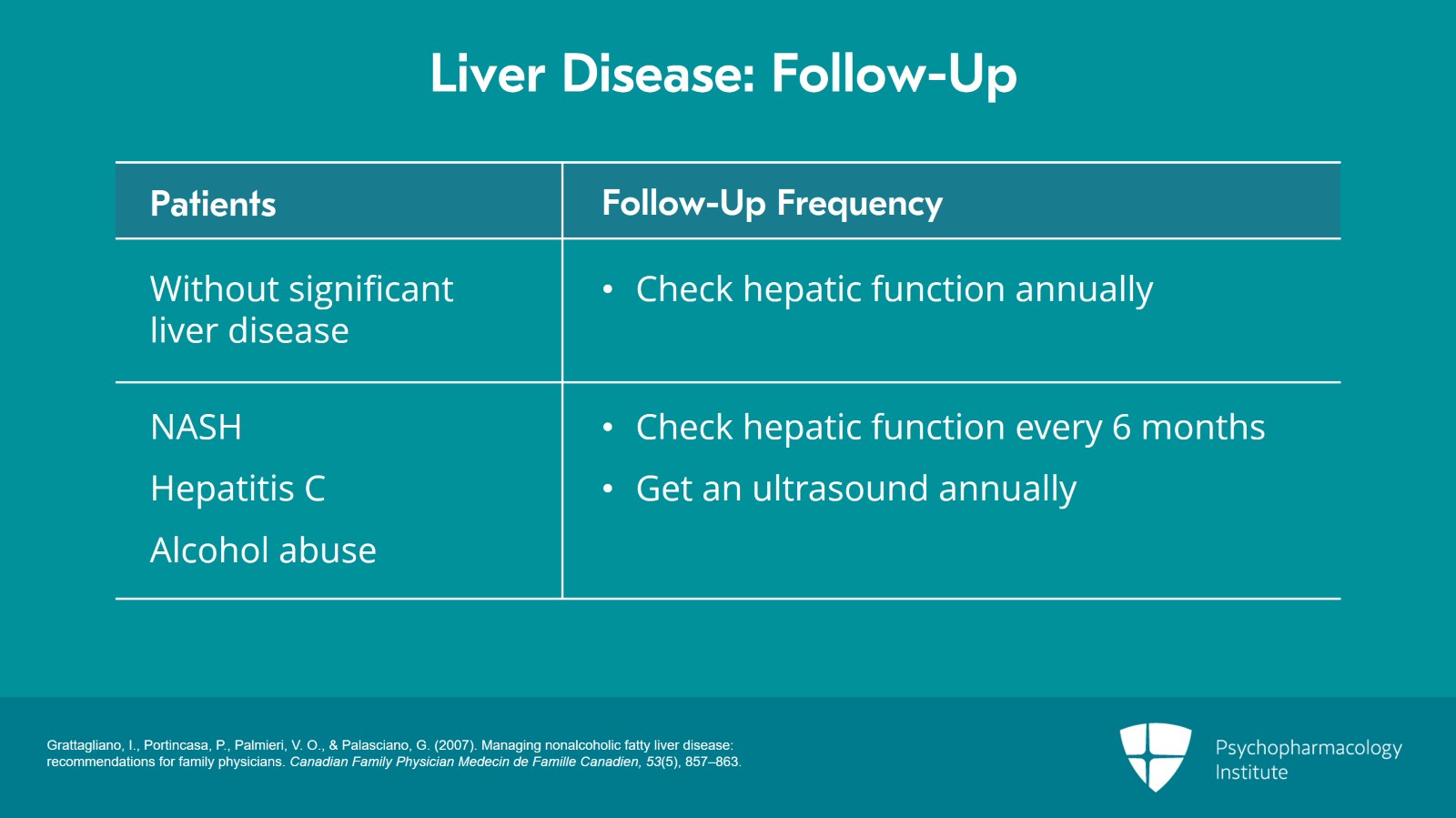

In general, for most people who do not have significant liver disease, we’re getting annual labs. We’ll have metabolic labs.

For those who have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, persistent hepatitis C, or alcohol abuse without cirrhosis, so these are people who would be cared for by their primary care provider and are not seen in a specialized clinic, the general rule of thumb is every six months for the labs and then they will get an ultrasound perhaps once a year to see how inflammation is progressing and to look for evidence of cirrhosis.

References:

- Grattagliano, I., Portincasa, P., Palmieri, V. O., & Palasciano, G. (2007). Managing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: recommendations for family physicians. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 53(5), 857–863.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 13 of 15

The key point here is that cytochrome P450 1A2 may be downregulated some in people who have significant systemic inflammation.

It’s a little bit of an oddball and most of it is going to apply to patients on clozapine. If you have people who have an inflammatory condition on clozapine be it COVID, influenza, bacterial pneumonia, check their clozapine level. That’s the most important way to figure out that particular situation.

Slide 14 of 15

Because ALT and AST do not determine whether a person with liver disease can metabolize a drug normally, you should not be relying on them. And most importantly, many clinicians are confused on this subject. And the type of people who say “well, if the ALT is abnormal, we can’t use X, Y, or Z drug” simply do not understand what they’re talking about.

What we do need and the labs which the FDA found best correlated with the extent of cirrhosis are serum albumin, INR and total bilirubin. How the FDA came to that is in the next section. And most importantly, there’s a very easy to use classification scheme. They give you points for these parameters and a couple of others to allow you to figure out, does my patient have moderate or severe hepatic dysfunction and require some dosage adjustments?

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.