Text version

Geriatric Depression Requires Distinct Approaches

If you have any older patients in your practice, you know how hard it can be to effectively treat their depressive symptoms. Much as child psychiatrists remind us that children are not just little adults, we also have to remember that geriatric patients may differ from their younger adult counterparts in many important ways. These include pharmacodynamic issues, side effect tolerance, and perhaps even the pathophysiology and nature of their depressive symptoms.

Treatment resistance is a major problem among older adults with depression. We can’t simply assume that the same algorithms that apply to younger adults will apply to older adults as well. Into this landscape comes the study we are looking at in more depth today.

Download PDF and other files

The OPTIMUM Trial Design

The trial is called OPTIMUM and stands for Optimizing Outcomes of Treatment-Resistant Depression in Older Adults. I have no idea how you get the acronym OPTIMUM from that study title, but there it is. In some ways, it’s akin to STAR*D but in older patients.

Today, we’re doing something a little bit different. Normally, we look at studies when they first come out, but today’s study from the New England Journal of Medicine in 2023 is important enough that we wanted to make sure it got covered even though it’s a couple of years old.

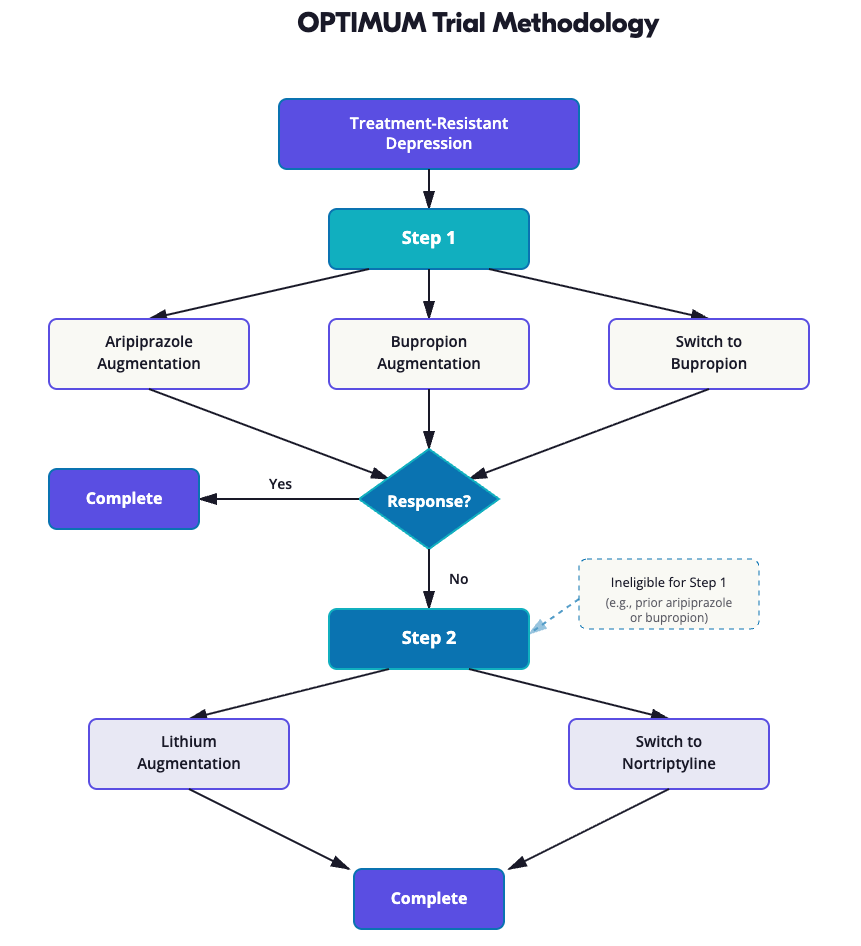

It’s a two-step open-label trial involving older patients with treatment-resistant depression that examines augmentation or switching strategies for antidepressant medication.

The open-label design meant patients and clinicians knew which medications were being received, which could influence results. Subjects who knew they were receiving two medications might have felt their depression was being better addressed than those receiving one. However, STAR*D was also open-label, and these trials better mimic real-world settings where patients know their treatments.

Sample Characteristics and Inclusion Criteria

All patients in this study were treatment resistant, meaning that they had failed at least two antidepressants at adequate dose and duration. The mean number of prior antidepressant trials was about 2.3. The mean age of patients in step 1 was 69 years, so these were somewhat younger older adults.

Most serious health conditions were excluded. 2/3 of the patients were female. 84% were white.

Download PDF and other files

Step 1: Three Treatment Arms

In the first step, patients were randomly assigned to one of three arms:

- Augmentation of their current antidepressant with aripiprazole

- Augmentation with bupropion

- A switch to bupropion

Bupropion is an interesting choice here because it was shown in STAR*D that augmentation with or a switch to bupropion was as effective or more effective than other strategies.

Step 2: Lithium or Nortriptyline

Patients who did not have remission or perceived benefit from step 1 of this trial, or who were ineligible for step 1 usually because they had already tried aripiprazole or bupropion previously, were then randomly assigned in step 2 to either:

- Augmentation with lithium

- A switch to nortriptyline

The authors note that the options for each step were based on recommendations from surveys of clinicians who specifically treat older adults with treatment-resistant depression.

Download PDF and other files

Psychological Well-Being as Primary Outcome

Outcomes of this study included psychological well-being, depression remission, and a variety of adverse events. Psychological well-being is an interesting primary outcome for a depression study. The authors note that it was chosen as a primary outcome based on advocacy from patients involved in the design of the trial as the measurement that would matter most to them.

Patient input is increasingly vital to designing research studies. Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI) grants—like the one funding this study are one example of research opportunities that focus on questions driven by patients themselves. They’re increasingly sought after by researchers, especially as the federal research funding landscape evolves.

One could imagine patients pointing out that the standard outcomes used in depression studies traditionally—either remission as demonstrated by a low score on a standard depressive scale, or response, a 50% or greater reduction in score on standard depressive instruments—may not matter as much to the individual as their perceived quality of life. The scale used to measure psychological well-being in this study includes elements like satisfaction, happiness, cognitive engagement, meaning, and purpose.

Aripiprazole Augmentation Outperformed Switch

In step 1, augmentation with aripiprazole improved well-being scores more than a switch to bupropion. Importantly, augmentation with bupropion didn’t separate out from either augmentation with aripiprazole or from a switch to bupropion when the authors employed their pre-specified p-value of 0.25.

In other words, we can’t say from this study that augmentation with aripiprazole was better than augmentation with bupropion in terms of the primary outcome. We also can’t say that augmentation with bupropion was better than a switch to bupropion. We can just say that augmentation with aripiprazole was better than a switch to bupropion.

On the other hand, remission occurred in about 28% of both augmentation groups compared to only 19% in the switch to bupropion group.

In step 2, the outcomes were similar between lithium augmentation and a switch to nortriptyline. Remission occurred in 19% of the former and 22% of the latter group.

Download PDF and other files

Falls Were Common Across All Arms

Looking at adverse effects, in step 1, bupropion augmentation was associated with the highest rates of falls. Just to underscore how common falls are among older adults with depression—even the arm with the lowest rate of falls, which was augmentation with aripiprazole, had a fall rate of one in every three patients over 10 weeks.

Almost 40% of patients in this study had had a fall in the six months before the study started. That’s a lot of falls. Some have pointed out that the doses of bupropion used in the study, up to 450 mg, were fairly high and titrated fairly quickly for older patients. This might have contributed to the increased rates of falls.

Similar rates of serious adverse events occurred in all three groups in step 1. In step 2, rates of falls and serious adverse events were similar between the two groups.

Authors Favored Aripiprazole Augmentation

Even though augmentation with aripiprazole didn’t separate out from augmentation with bupropion in terms of well-being scores, the authors here concluded that augmentation with aripiprazole may be a better overall strategy in older adults than augmentation with or switch to bupropion. This was based on both outcomes and adverse events.

Download PDF and other files

Challenges: Low Remission and Adherence Issues

It is important to note that all examined interventions had relatively low rates of remission. Fewer than a third of patients in any arm achieved remission during the 10-week study. Adherence was also a significant issue:

- In Step 1, 70% were adherent to augmentation, while only 40% were adherent to bupropion monotherapy.

- In Step 2, only 50% of patients were adherent to either treatment arm.

- Overall, fewer than 10% of patients switching to bupropion or augmenting with lithium achieved target dose and remission.

It’s interesting to me that more patients were adherent to augmented regimens in step 1 than the monotherapy regimen. That’s probably the opposite of what I would have expected. Augmentation has been shown in several previous trials to be more effective than switching, but there’s concern from experts that augmentation may lead to more adverse effects and drug-drug interactions. You might think that would decrease adherence.

I suppose the fact that adherence was better for the augmentation arms here could speak to the downside of open-label trials. Patients might have been aware of the possibility of augmentation and assumed that was better. This could cause them to have less faith in the monotherapy regimen and perhaps be less adherent.

Polypharmacy Did Not Increase Falls

I’m impressed that augmentation actually produced fewer falls than monotherapy, though again all groups had high rates of falls. This counters the prevailing wisdom that polypharmacy would lead to more falls.

It reminds me of a study we looked at last year that showed that sedative-hypnotic prescriptions were actually associated with a lower risk of falls immediately after their prescription. The idea there was that treating insomnia actually reduces falls. Perhaps this study is showing that treating depression—therefore probably improving sleep—reduces fall risk as well.

Download PDF and other files

No Clear Difference in Adverse Events

The fact that major adverse events did not differ between arms also provides more reassuring data about the use of antipsychotics like aripiprazole in older adults. We sometimes get concerned about rates of akathisia with aripiprazole. It doesn’t seem like that was a major issue here, as perceived feelings of tension or inner distress were similar among groups.

Some letters that were written following this article also point out some risk of tardive dyskinesia with aripiprazole, though less than with other antipsychotics. The duration of the study is probably not sufficient to capture this particular side effect.

Lithium and Tricyclics in Older Adults

While lithium didn’t perform as well here as we might have hoped in terms of effectiveness and adherence, it’s a good reminder to not shy away from using lithium in older adults for safety concerns. I often see trainees do this. There is no clear difference in rates of serious adverse events in the lithium group compared to any of the other groups.

And for all the concerns about using tricyclics in older adults given anticholinergic and alpha blocking effects, that group actually had a numerically lower rate of falls than the lithium or bupropion augmentation groups. One important caveat is that the study included fewer patients than originally hoped. It may have been underpowered to detect meaningful differences in adverse events, so we want to be cautious about drawing conclusions there.

Download PDF and other files

Clinical Practice Implications

At the end of the day, how is this study going to influence my clinical practice? I do think it may make me consider augmentation with aripiprazole more readily in older adults. This is something I typically think about more with younger patients. We can’t know from this study whether the same benefit would extend to augmentation with other antipsychotics; there does generally seem to be something unique about aripiprazole in this regard.

It may also make me less likely to try bupropion monotherapy in older adults, especially for those who have already failed two other trials. I can’t say I was doing that much before reading this study, but it does seem to be pretty clearly inferior here. This makes the findings different from those of STAR*D in younger adults.

One important caveat when considering the conclusions regarding augmentation versus switching: as one letter pointed out, this could also indicate that the initial antidepressants were working better than was recognized. The lack of efficacy of the switch might be more related to the discontinuation of those initial agents.

Finally, it’s interesting to me that mirtazapine wasn’t included in this study either as monotherapy or augmentation, as that seems to be the current strategy of choice for older patients. It’s certainly the most common thing we see primary care physicians doing. I would be very curious to see how that strategy stacks up against augmentation with aripiprazole or bupropion, both in terms of efficacy but also in terms of side effects. Hopefully, that will be a future study we can examine on Quick Takes.

Abstract

Antidepressant Augmentation versus Switch in Treatment-Resistant Geriatric Depression

Eric J. Lenze, M.D., Benoit H. Mulsant, M.D., Steven P. Roose, M.D., Helen Lavretsky, M.D., Charles F. Reynolds III, M.D., Daniel M. Blumberger, M.D., Patrick J. Brown, Ph.D., and Jordan F. Karp, M.D.

Background

The benefits and risks of augmenting or switching antidepressants in older adults with treatment-resistant depression have not been extensively studied.

Methods

We conducted a two-step, open-label trial involving adults 60 years of age or older with treatment-resistant depression. In step 1, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to augmentation of existing antidepressant medication with aripiprazole, augmentation with bupropion, or a switch from existing antidepressant medication to bupropion. Patients who did not benefit from or were ineligible for step 1 were randomly assigned in step 2 in a 1:1 ratio to augmentation with lithium or a switch to nortriptyline. Each step lasted approximately 10 weeks. The primary outcome was the change from baseline in psychological well-being, assessed with the National Institutes of Health Toolbox Positive Affect and General Life Satisfaction subscales (population mean, 50; higher scores indicate greater well-being). A secondary outcome was remission of depression.

Results

In step 1, a total of 619 patients were enrolled; 211 were assigned to aripiprazole augmentation, 206 to bupropion augmentation, and 202 to a switch to bupropion. Well-being scores improved by 4.83 points, 4.33 points, and 2.04 points, respectively. The difference between the aripiprazole-augmentation group and the switch-to-bupropion group was 2.79 points (95% CI, 0.56 to 5.02; P=0.014, with a prespecified threshold P value of 0.017); the between-group differences were not significant for aripiprazole augmentation versus bupropion augmentation or for bupropion augmentation versus a switch to bupropion. Remission occurred in 28.9% of patients in the aripiprazole-augmentation group, 28.2% in the bupropion-augmentation group, and 19.3% in the switch-to-bupropion group. The rate of falls was highest with bupropion augmentation. In step 2, a total of 248 patients were enrolled; 127 were assigned to lithium augmentation and 121 to a switch to nortriptyline. Well-being scores improved by 3.17 points and 2.18 points, respectively (difference, 0.99; 95% CI, −1.92 to 3.91). Remission occurred in 18.9% of patients in the lithium-augmentation group and 21.5% in the switch-to-nortriptyline group; rates of falling were similar in the two groups.

Conclusions

In older adults with treatment-resistant depression, augmentation of existing antidepressants with aripiprazole improved well-being significantly more over 10 weeks than a switch to bupropion and was associated with a numerically higher incidence of remission. Among patients in whom augmentation or a switch to bupropion failed, changes in well-being and the occurrence of remission with lithium augmentation or a switch to nortriptyline were similar. (Funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; OPTIMUM ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02960763.)

Download PDF and other files

Reference

Lenze, E. M.D., Mulsant, B. M.D., Roose, S. M.D., Lavretsky, H. M.D., Reynolds III, C. M.D., Blumberger, D. M.D., Brown, P. Ph.D., & Karp, J. M.D. (2023). Antidepressant Augmentation versus Switch in Treatment-Resistant Geriatric Depression. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2023;388:1067-1079