Slides and Transcript

Slide 1 of 16

I’d like now to continue our discussion particularly of pharmacotherapy treatment options for older adults with major depressive episodes or with recurrent major depression disorder as the case may be.

The centerpiece of this part of our time together is a suggested antidepressant algorithm for older adults.

Slide 2 of 16

There are several guiding principles here. First, we are always trying to tailor treatments to the specific needs of our patient. Talk about personalizing treatment, that really means tailoring the treatment to the specific needs of the patient as well as taking into account their values and preferences.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. III., Lenze, E., & Mulsant, B. H. (2019). Assessment and treatment of major depression in older adults. In DeKosky, S. T., Asthana, S. (Eds.), Geriatric neurology (1st ed., Vol. 167, pp. 429–436). Elsevier Science Ltd.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 3 of 16

So in this context although it seems obvious, we don’t retry a drug class, for example, SSRIs that have already failed an adequate trial. If we have questions about the adequacy of the trial, we may retry it at that point. Obviously also, we’re not going to retry a specific medication if there is good evidence that the patient was previously intolerant to it or it poses a safety hazard based upon our medical evaluation of the patient.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Slide 4 of 16

We do like to try a specific medication that worked previously although we are aware that with each succeeding episode, the risk for an incidence of treatment-resistant depression increases.

We are also mindful about drug interactions and known risks and this is particularly the case with some of the older tricyclic antidepressants. There is a place for the tricyclics and I’ll talk about that momentarily.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical. 4

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 5 of 16

Finally, we emphasize the importance of giving an adequate trial which for us means at four-plus weeks at an effective dose and maximizing the dose as tolerated before augmenting the primary medication, augmenting it with another agent or switching it to another class of antidepressants.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical. 5

Slide 6 of 16

We also are strong proponents of the use of depression-specific psychotherapies particularly cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy for depression, problem solving therapy and behavioral activation. There is good evidence that the combination of antidepressant medication and a depression-specific psychotherapy works well to assuage the symptoms of depression in many older adults.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical. 6

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 7 of 16

In terms of augmentation strategies, my colleagues and I have published the largest placebo-controlled augmentation strategy RCT using aripiprazole. This was published with Eric Lenze as the first author in the Lancet in 2015. And we found that the use of aripiprazole in doses of 2 to 15 mg daily was effective in relieving depressive symptoms and bringing about remission in patients who had failed to respond adequately to adequate antidepressant doses of venlafaxine up to 300 mg for up to 12 weeks.

Quetiapine is also another agent in this category that may be useful for an augmentation strategy.

References:

- Lenze, E. J., Mulsant, B. H., Blumberger, D. M., Karp, J. F., Newcomer, J. W., Anderson, S. J., Dew, M. A., Butters, M. A., Stack, J. A., Begley, A. E., & Reynolds, C. F. (2015). Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole for treatment-resistant depression in late life: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet, 386(10011), 2404-2412

Slide 8 of 16

In patients who’ve not responded to augmentation or switching, we think that there is a third tier in our algorithm or set of strategies.

We might switch them to the use of nortriptyline for which there does exist abundant evidence for its efficacy in older adults when steady state levels of 80 to 120 ng/mL are achieved or for augmentation with lithium carbonate.

There may be a place in older adults for ketamine or esketamine but this is not yet well established in older adults to the extent that has been established in midlife adults.

And of course, we also will use various neurostimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation or ECT, the latter particularly in cases of psychotic depression or in cases where suicide risk is acute or imminent.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. III., Lenze, E., & Mulsant, B. H. (2019). Assessment and treatment of major depression in older adults. In DeKosky, S. T., Asthana, S. (Eds.), Geriatric neurology (1st ed., Vol. 167, pp. 429–436). Elsevier Science Ltd.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 9 of 16

Let me summarize a few key points as well about the pragmatic usage of these different compounds.

Usually when we talk about acute treatment, that is to say a treatment that is directed at the acute episode of depression with the goal of bringing about remission, short-term or acute treatment typically lasts on the order of 12 to 16 weeks but may last as long as 24 to 28 weeks if a second- or third-line agent is used.

The important principles of acute phase pharmacotherapy in older adults though encompass the time-honored adage, start low with respect to dose, go slow but go all the way.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. III., Lenze, E., & Mulsant, B. H. (2019). Assessment and treatment of major depression in older adults. In DeKosky, S. T., Asthana, S. (Eds.), Geriatric neurology (1st ed., Vol. 167, pp. 429–436). Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Slide 10 of 16

As I’ve also emphasized, I like to educate both my patients and their family caregivers about the rationale for treatment and the importance of adherence to achieve full symptomatic remission. I can’t underscore that point importantly as it is enough.

If a second augmentation agent is needed, maybe aripiprazole, or lithium carbonate, or quetiapine.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. III., Lenze, E., & Mulsant, B. H. (2019). Assessment and treatment of major depression in older adults. In DeKosky, S. T., Asthana, S. (Eds.), Geriatric neurology (1st ed., Vol. 167, pp. 429–436). Elsevier Science Ltd.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 11 of 16

If a second agent is required for the achievement of remission, it is also very likely to be necessary to sustain remission. This has been shown particularly in the context of a different but related disorder namely psychotic depression where the combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic is necessary both to bring about remission and to sustain remission and to prevent relapse and recurrence. I refer you specifically to the recent landmark study led by Alastair Flint at the University of Toronto and published in JAMA in 2019.

And finally, I would emphasize that the dose that gets you well is the dose that keeps you well. In other words, a common error in practice is that dosage should not be decreased once remission is obtained. Doing so puts the patient at higher risk for relapse into the current episode or recurrence of a new episode.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. III., Lenze, E., & Mulsant, B. H. (2019). Assessment and treatment of major depression in older adults. In DeKosky, S. T., Asthana, S. (Eds.), Geriatric neurology (1st ed., Vol. 167, pp. 429–436). Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Flint, A. J., Meyers, B. S., Rothschild, A. J., Whyte, E. M., Alexopoulos, G. S., Rudorfer, M. V., Marino, P., Banerjee, S., Pollari, C. D., Wu, Y., Voineskos, A. N., Mulsant, B. H., & STOP-PD II Study Group (2019). Effect of Continuing Olanzapine vs Placebo on Relapse Among Patients With Psychotic Depression in Remission: The STOP-PD II Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 322(7), 622–631.

Slide 12 of 16

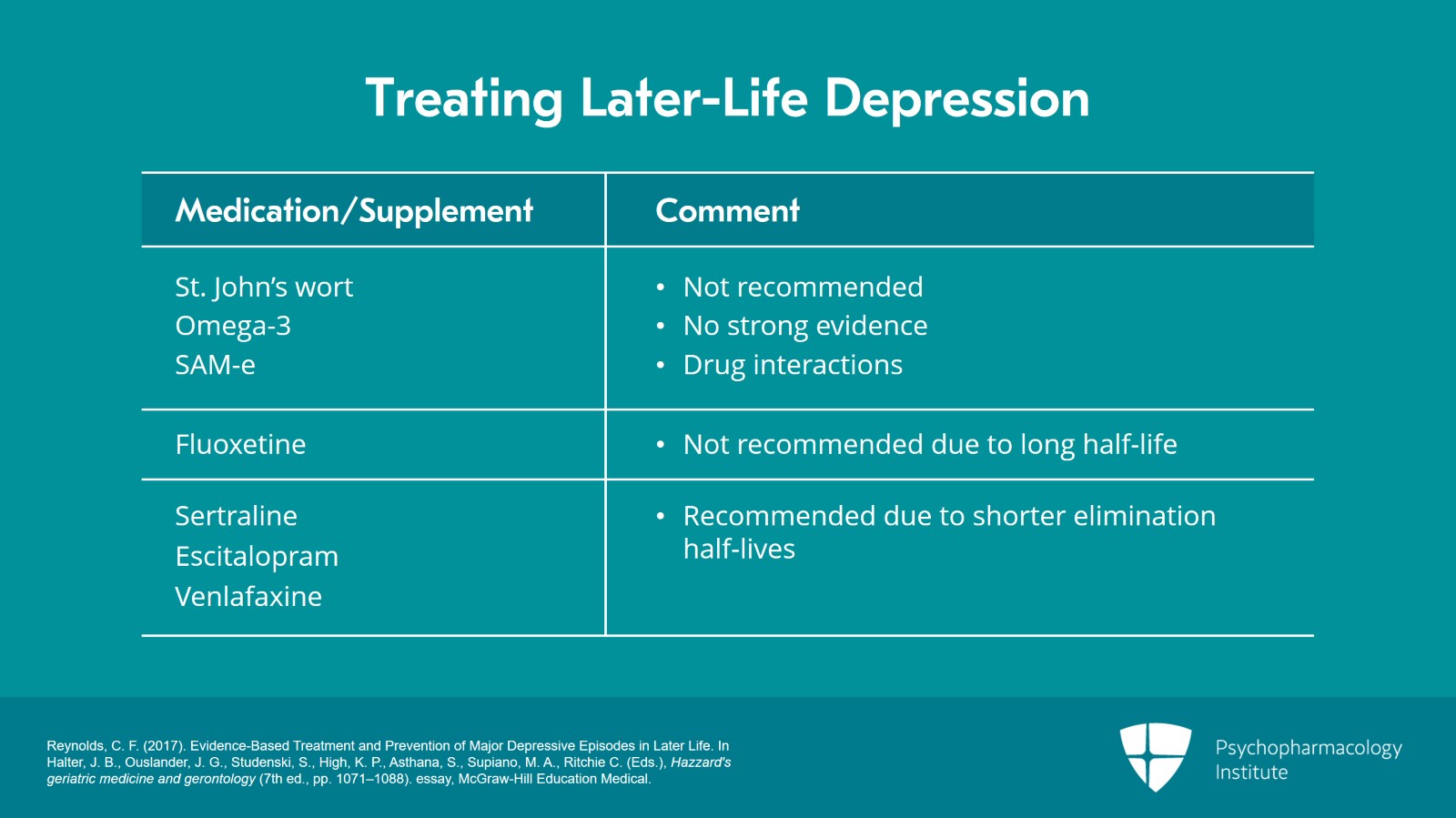

I generally recommend against the use of things like St. John’s wort, omega-3 or SAM-e because I’m not convinced that the evidence is strong and because in some instances I’m concerned about drug-drug interactions.

I’ve also generally not used fluoxetine in my practice because of its long half-life. I prefer agents with shorter elimination half-lives like sertraline, escitalopram or venlafaxine.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 13 of 16

And I would emphasize that again that a past history of good response to a particular medication may provide useful guidance for treatments of a recurrent episode after being sure of treatment adherence.

References:

- Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment and Prevention of Major Depressive Episodes in Later Life. In Halter, J. B., Ouslander, J. G., Studenski, S., High, K. P., Asthana, S., Supiano, M. A., Ritchie C. (Eds.), Hazzard's geriatric medicine and gerontology (7th ed., pp. 1071–1088). essay, McGraw-Hill Education Medical.

Slide 14 of 16

So to summarize, the key take-home points here, first-line antidepressant pharmacotherapy in older adults with major depression consists primarily in this day and age of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors as well as bupropion.

Secondly, an adequate trial is defined in terms of an appropriate dose of medication taken for a sufficient period of time in order to make a reliable judgment about its effectiveness. And to get to that point of being able to make a reliable judgment, it’s imperative to educate patients and their caregivers about the rationale for treatment and the importance of good treatment adherence.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.

Slide 15 of 16

Nonresponders will need switching to another class of medication or to a neurostimulatory therapy like ECT.

Partial responders may benefit from either switching to another class of medication, to augmenting the first medication with a second or to the addition of a depression-specific evidence-based psychotherapy like CBT, IPT, problem solving therapy or some form of behavioral activation.

Thank you.

Free Files

Download PDF and other files

Success!

Check your inbox, we sent you all the materials there.